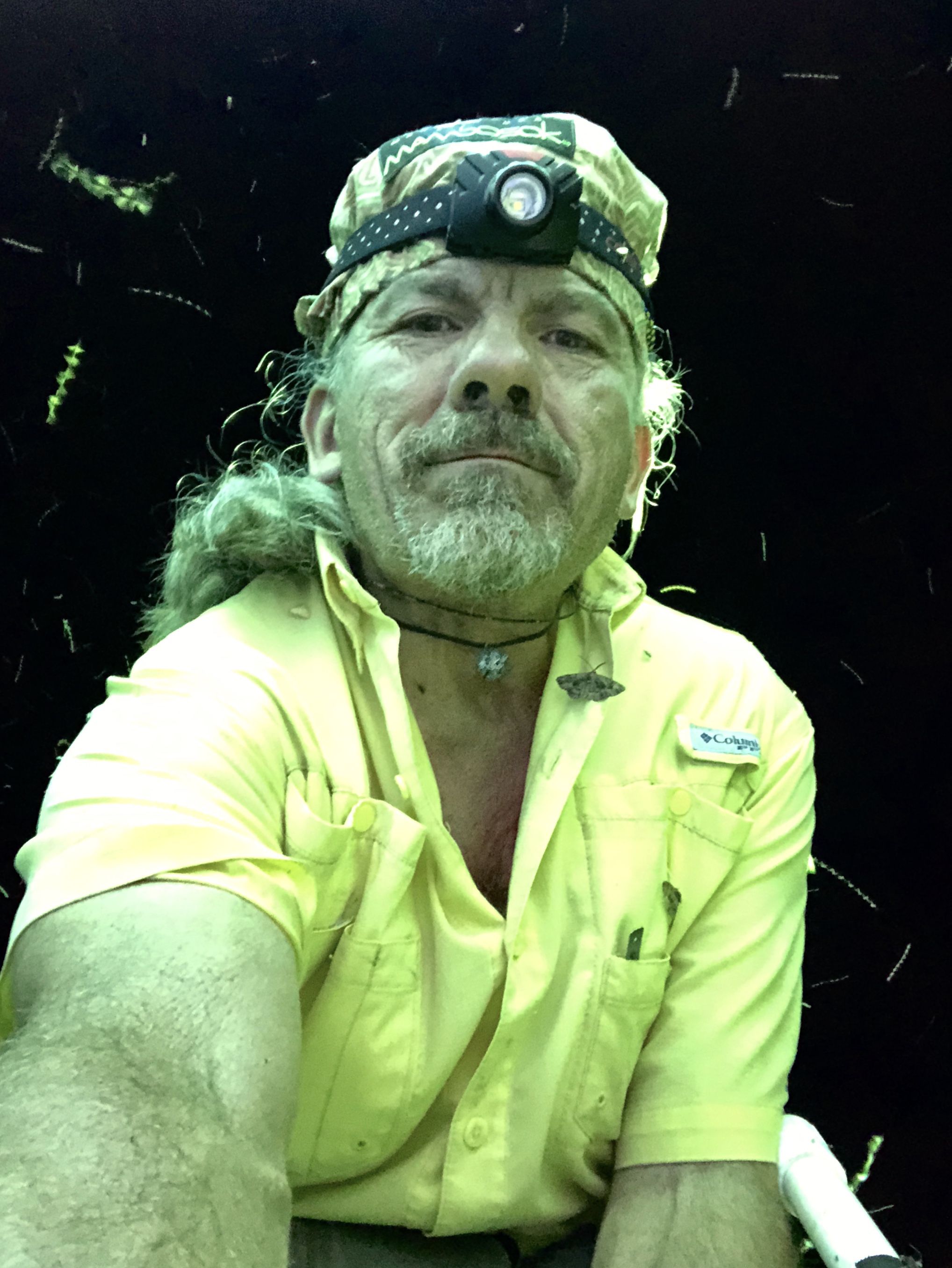

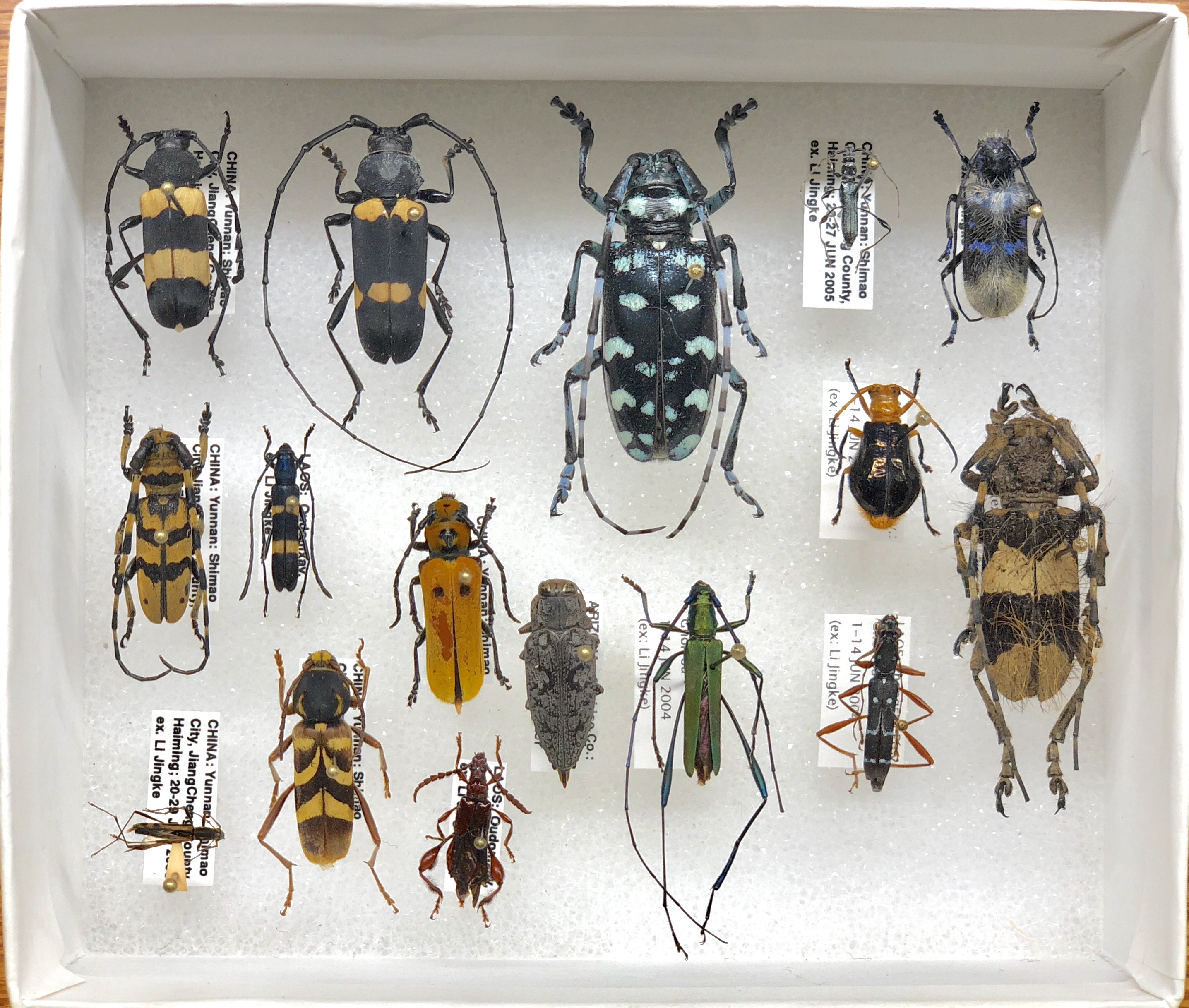

Welcome to the 11th “Collecting Trip iReport”; this one covering a very short (4 days) trip to northwestern Oklahoma on May 3–7, 2022. My collecting partner for this trip was long-time friend and hymenopterist Mike Arduser. Mike is one of the best natural historians that I know and, like me, has a special love for the often overlooked beauty of western Oklahoma and its fascinating insect fauna. It had been 13 years, however—too long, in my opinion, since our last joint field trip when we sampled the bee (Mike) and beetle (me) fauna at The Nature Conservancy’s Four Canyon Preserve in Ellis Co. Thus, I was happy for the chance to once again spend some time in the field with such a knowledgeable naturalist in an area we that both know and love.

As with all previous “iReports” in this series, this report is illustrated exclusively with iPhone photographs (thus the term “iReport”). Previous iReports in this series include:

– 2013 Oklahoma

– 2013 Great Basin

– 2014 Great Plains

– 2015 Texas

– 2018 New Mexico/Texas

– 2018 Arizona

– 2019 Arkansas/Oklahoma

– 2019 Arizona/California

– 2021 West Texas

– 2021 Texas/New Mexico/Arizona

Day 1 – Gloss Mountain State Park (Major Co.)

It took most of the day to get here—Tulsa threw us a couple of obstacles in the form of a construction-mediated wrong turn and a motorcycle engulfed in flames. I’ve been to Gloss Mountain a number of times, but never this early in the season. Skies were sunny (unlike St. Louis when we left this morning), but temps didn’t get much above 60°F and even dropped down into the upper 50s before we finished up at sunset.

Surprisingly, despite the earliness of the season and cool temps, beating was quite productive. Working the low areas around the parking lot, I beat a fair number and diversity of beetles and hemipterans—mostly chrysomelids—but only a single Agrilus sp. off of Prosopis glandulosa.

I knew there were other trees, principally Celtis reticulata (net-veined hackberry) and Sapindus drummondii (soapberry), on top of the mesa and wanted to see if anything was on them. Bingo! Even before reaching the top, I beat a few Agrilus (several spp.) from the Celtis, and up on top I beat quite a few more off the same. There were also additional mesquite trees up top, off which I again beat a single Agrilus sp. along with a few other things, notably a series of ceresine treehoppers. The Sapindus was just starting to leaf out, and I found nothing by beating them other than a single ceresine. A notable find was the pile of larval frass of Plinthocoelium suaveolens (bumelia borer) at the base of a living Sideroxylon lanuginosum (gum bumelia) tree—a sure sign of active infestation by a beetle I have yet to formally record from this place.

On the way back down from the top, we hit the sunset perfectly as it “touched” a peak in the foreground! Despite my success here this evening, Mike saw no bees of interest on the few flowers that were found due to the cold temps and chilling winds, so tomorrow we will continue west hoping for warmer conditions on the western edge of Oklahoma.

Back in town, we searched for an open sit-down restaurant—fruitlessly because of the late hour—and ended up with a mediocre breakfast burrito from a fast food shop I’ve never been to before. The local Buick dealership, however, with its 1950s neon lights shining brightly in the night sky, was a taste of Americana that makes these trips so enjoyable. Life on the road!

Day 2 – Black Mesa State Park (Cimmaron Co.)

Welp! We awoke this morning to cold temps (low 60s), thick fog, and low hanging clouds, and the forecast for the area showed essentially no improvement through at least the day. Our plan had been to hit a spot about an hour southwest before heading back north to Beaver Dunes State Park, but the forecast for both those areas also was cold and wet. It was not until we looked at the forecast for Black Mesa—our last planned stop of the trip and a 4½-hour-drive to the west—that the forecast seemed to be in our favor, so we decided to blast on out there. We figured we would get there at about 2:00 pm and could spend the rest of the day there collecting, camp there tonight, and start heading back east tomorrow (assuming the forecast improved for the areas we missed).

Wrong! When we got there, it was not only cloudy and cold, but dry as a bone! Even if it had been sunny with warmer temps, there still would not have been any insect activity to speak of. The leaves of oaks and hackberries in the area were just barely starting to break bud, and the only flowers we saw at the park were a large willow in full bloom—but not a single insect visiting them. Knowing that there was no other place where conditions were better that we could drive to within the next couple of hours and collect for at least a short time, we instead decided to make it a hiking day and hike the High Point Trail at nearby Black Mesa Nature Preserve.

Black Mesa Nature Preserve (Cimmaron Co.)

When we arrived and looked at the signage, we learned that the hike to the oracle at the official high point would be a more than 8-mile hike! Just reaching the top of the mesa itself would be a more than 3-mile-hike, with the high point another mile on top. Not knowing if we had the appetite for such a distance (or time to do it before sunset) and with the wind cold and biting, we started out anyway and gave ourselves permission to turn around at any point if we felt like it.

Nevertheless, we persevered. We checked the cholla (Cylindropuntia imbricata) along the way hoping to see Coenopoeus palmeri (one of the cactus longhorns, which I’m not sure has been recorded from Oklahoma) or at least one of the more widespread Moneilema species, but none were seen (nor really expected). The trail up the side of the mesa was steep and spectacular, and the trail atop the mesa was surreal—especially given the cold winds and low-hanging clouds. Eventually, we made it to the official high point and enjoyed the fun facts carved into each side of the granite obolisk marking the spot.

Coming back down was not much easier than going up, the steepness of the trail jamming my toes into the toe box of my new hiking boots (which performed admirably!), but I did find an insect—a largish black weevil torpidly crawling on the trail. Even on the relatively level lower portion of the trail once we got there was difficult, our legs really starting to feel the miles now. As we hiked the last mile back to the car, the temperature continued to plummet as it started to sprinkle, turning to rain soon after we reached the car and then heavy rain as we headed down the highway back to the east. The irony of the situation—rain coming to a parched landscape just when we are ready to leave—did not escape us. We’ll spend the night in Boise City and hope for a better forecast tomorrow!

Day 3 – Beaver Dunes State Park (Beaver Co.)

Temps were down in the mid-40s when we awoke this morning, but skies were sunny and we were heartened by a promising forecast of continued sun and highs in the low to mid-60s. Our first destination—Beaver Dunes—was a relatively short 2-hour drive further east, and when we arrived sunny skies still prevailed. Unfortunately, temps still hovered in the mid-50s with a biting wind that made using the beating sheet difficult to impossible.

That said, I managed to beat a fair series of Agrilus spp. (probably mostly one species) and a few other beetles off living Celtis reticulata (net-veined hackberry) dotting the roadside along the entrance to the Picnic Area. Under the main group of hackberries I noticed new growth of Cucurbita foetedissima (buffalo gourd) along with last year’s dead stems. I’ve never collected Dorcasta cinerea (a longhorn beetle that utilizes buffalo gourd as a larval host), so I began splitting open the old stems to see if I could find unemerged adults. I didn’t, but what I did note inside the stems was evidence of boring by some insects and, eventually, the tiniest little scolytine bark beetles that I’ve ever seen. They were always found right at the node, usually in pairs (perhaps male and female?), and I ended up collecting a series of about a dozen specimens from two different stems.

Also in the main group of hackberries, I noticed a dead branch hanging from the tree, which had fallen but gotten snagged on a lower branch to remain off the ground. The branch was obviously infested and showed a few emergence holes indicative of both buprestids and cerambycids, and when I broke into it I found two unemerged adult Agrilus (different species), which caused me to cut and bundle the branch to being back for rearing. At the entrance, I went to examine the stand of yellow flowers that greeted our arrival, determining them to be Pyrrhopappus pauciflorus (smallflower desert-chicory, Texas false dandelion). While I was on the ground photographing the flowers, I noticed a red and black hister beetle that proved to be Spilodiscus sp.—aptly named considering the two red maculations on the elytra. I also noticed a couple of tiger beetle larval burrows in the hard-packed sandy soil and found a long, thin plant stem to “fish” the larvae out. I managed to snag the larva in one of the burrows, which I believe is Tetracha carolina (Carolina metallic tiger beetle) by virtue of the thin white margin around the prothorax and the open habitat in which the larval burrow occurred. If this is true, then it is a second instar because it is slightly smaller than a typical Cicindela sp. third-instar larva.

Afterwards, I went over to the dunes to see if Mike had found anything, but temps were still too cold to see anything flying. He did, however, show me an interesting stand of Penstemon that he’d found and that we determined to be P. fendleri (Fendler’s penstemon). The plants were all on the north side of the dune in apparently protected spots, and I noted that on iNaturalist our observation was the northernmost record for the species (save one suspicious, disjunct Colorado record).

On the way back to the car, I beat a few more beetles off living Celtis reticulata. By now, we’d seen all we needed to see here and decided to head southeast to one of the Brachys barberi locations (that were the reason for this trip in the first place).

5 mi E of Harmon (Ellis Co.)

This

Recently, another coleopterist collected Brachys barberi—more typically a southwestern species—on Quercus harvardii (shinnery oak) at this spot. I’ve not managed to find the species myself yet, and as it was collected on May 3rd last year I hoped the timing would be right. Quercus havardii dominated the landscape at this spot, mostly as thick stands of low-growing shrubs but also as a copse of small trees.

At first, I swept the lowest-growing plants, collecting a variety of mostly chrysomelids and curculionids and even one Agrilus sp., before moving to beating along the sunny edges of the patches of taller shrubs and collecting similar species (but no Agrilus sp.). Just to the north, I noticed a stand of individuals tall enough to be considered trees (presumably a clonal stand) and began beating them. Immediately I began collecting not only the chrysomelids and curculionds that I was collecting before, but also several Agrilus spp. and what must be Agrilaxia texana—a species represented in my cabinet by just two specimens that I collected in northeastern Texas way back in 1984.

I worked nearly the full perimeter of the copse, noticing that most of the beetles were being collected only on the south-facing sunny (and leeward) side. When I was just about ready to call it quits, a much larger black and yellow beetle landed on the sheet. For an instant I thought it was a lycid, but it moved characteristically like a longhorned beetle, and I quickly realized that I had collected Elytroleptus floridanus—a quite rare southeastern U.S. species that I have only seen once before when I reared a single individual from dead oak that I collected in the Missouri bootheel (and representing a new state record). I wasn’t sure the species had ever been recorded from Oklahoma, so I found Gryzmala’s revision of the genus online and saw that it had been previously recorded from the state—but all the way over on the east side near the border of Arkansas. All records from Texas as well are from the eastern side of the state, so today’s capture appears to represent a significant northwestern extension of the species’ known geographic range by about 300 miles!

Sadly, I never saw Brachys barberi, but collecting Elytroleptus floridanus (in Oklahoma!) was a pretty good consolation prize.😊

Day 4 – Prologue (“Good to Go” coffee shop)

We awoke to bright sunny skies, and though a tad chilly it was still warmer than the previous mornings and with a good forecast to boot! It would take about an hour to drive to the day’s collecting spot—the one and only Gloss Mountain State Park (where we visited briefly a few days ago to start the trip), but not until after an unexpected and hilariously bizarre experience at a coffee shop in town called “Good to Go”.

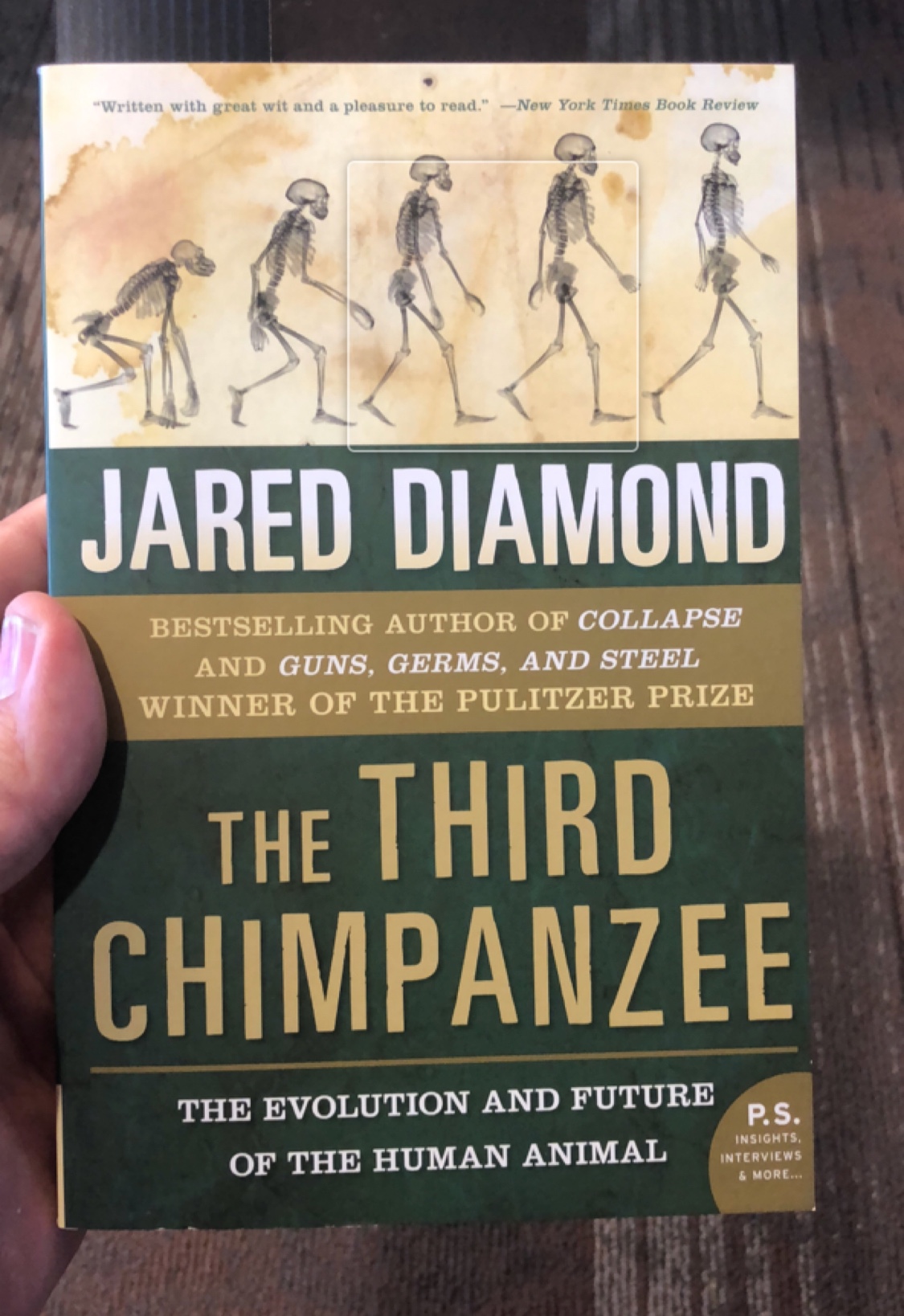

Mike was the first to notice the velociraptor in the lounge—saddled up for a ride! Okay, that’s cute. Then he noticed the sign on the outdoor display that read “Stegosaurs roamed the Earth about 5,000 years ago.” At first I thought, okay, they’re a little confused on the timeline, but what they’re trying to say is that dinosaurs lived a long time ago.

Then I noticed a granite plaque in the background that clearly read “The Holy Bible”, and it dawned on me that we had entered a creationist’s den! Had we not already ordered our coffee, I might have surreptitiously tiptoed my long-haired hippy butt out of there before somebody pointed at me and began slowly chanting “Lucifer!”

Once we were outside the shop, our coffee secured and the need for hushed tones no longer muffling our reactions, we took a quick walk with the dinosaurs to admire their seeming scientific accuracy. I was impressed with the T. rex in particular, it’s body axis realistically horizontal with the tail straight and strong—not the lumbering, upright, tail-dragging version that I learned about as a kid. At least they were accepting some of the current body of scientific evidence on dinosaurs and ignoring only that dealing with their age—or so I thought…

The stegosaur as well appeared to be fairly accurately rendered, its tail also straight and strong and a youngster trailing closely behind, until I noticed something atop the adult—an angel riding it! ‘God’s creatures big and small’, I guess.

The coup de grace was the information plaque behind the stegosaur. Rather than providing information on dinosaurs, I was instead treated to a barrage of hilariously unsupported claims advocating the idea that humans and dinosaurs once lived together. Each “factoid” on the plaque was more bizarre and quotable than the one before. Did you know that the adult stegosaur probably died 4,000 years ago in the Great Flood, but that the baby—happily—likely survived by getting a ride on the Ark with Noah! And all that scientific evidence that pinpoints the Cretaceous extinction to 65 million years ago? Apparently it has merely been fabricated as part of a global conspiracy because scientists just don’t want to agree with the Bible. I just about lost it, however, when I reached “It is uncertain if humans ever rode Dinosaurs, but there is overwhelming evidence that humans saw living dinosaurs.” I mean—What?!

Our unplanned morning entertainment now done, we hit the road for our next—and final—collecting spot for the trip.

Gloss Mountain State Park (Major Co.)

We arrived at about 10 am with a plan to spend the rest of the day there—whether the collecting was good or bad, this would be our final stand. We hiked up to the mesa, stopping at an accessible spot about halfway up to work the trees (me) or set out pan traps (Mike). Beating the Celtis reticulata (net-veined hackberry) yielded a similar assortment of beetles as last time—a couple of Agrilus spp. along with the occasional chrysomelid or curculionoid and a few other beetles, and the same was true with Prosopis glandulosa (mesquite), with the exception that I did not find any Agrilus this time.

Atop the mesa, I decided to do an entire perimeter hike—something I’ve always wanted to do but never actually accomplished. The idea was to beat all of the C. reticulata, P. glandulosa, and Sapindus drummondii (soapberry) that I could find in an effort to “leave no stone unturned” in my quest for beetles. Soon after starting out, I saw a nice Pasimachus elongatus ground beetle running across the mesa top and “forced” it to cooperate for photos by pinning a hind tarsus to the ground with my finger tip (barely visible in the upper left side of the photo). I collected it, as well as another that I saw a short distance away, and then proceeded with the beatings! Beating the C. reticulata was quite productive, with perhaps three Agrilus spp. and numerous other beetles being collected off of nearly every tree that I beat. Beating P. glandulosa also was productive for various beetles, though again no Agrilus were encountered. The biggest surprise came when I started beating S. drummondii, most of which were still in the earliest stages of leafing out. I got nothing from most of the trees (the majority of which were clustered in a small copse near the front of the mesa), but in the back part of the cluster were a couple of trees with noticeably more foliage—beating them yielded perhaps a dozen Agrilus limpiae, a soapberry specialist that I haven’t seen in numbers since 1986 when I collected a series on soapberry in south-central Kansas.

I rarely get anything beating Sideroxylon lanuginosum (gum bumelia), but I beat most of the trees that I saw anyway and collected one cryptocephaline chrysomelid and two curculionoids. A single Eleodes hispilabris (apparently on its last leg) was seen near the north end of the mesa, which I photographed and collected, and on the way back I encountered a small patch of Sphaeralcea coccinea (scarlet globemallow) in bloom, from the flowers of which I collected a few small melyrid-type beetles and a small halictid bee for Mike. Also on the north part of the mesa I saw a young eastern collared lizard (Crotaphytus collaris), who posed just long enough for me to get off a shot before blasting away from my approaching lens.

Throughout the hike atop the mesa I kept my eye out for “new-to-me” plants (of which there are many), finding for the first time Toxicodendron rydbergii (western poison ivy) and blooming individuals of Chaetopappa ericoides (rose heath). Physaria gordonii (Gordon’s bladderpod)—a relative of the federally threatened P. filiformis (Missouri bladderpod)—was blooming abundantly atop the mesa. At this point, Mike and I rejoined and relayed to each other our more notable findings. For Mike’s part, he had seen a couple of cacti that I had missed—Escobaria missouriensis (Missouri foxtail cactus) and Echinocereus reichenbachii perbellus (black lace cactus)—and took me to the spots where he had seen them. While retracing our steps, we also found Gaillardia suavis (pincushion daisy, perfumeballs) and the strikingly beautiful Penstemon cobaea (cobaea beardtongue, prairie beardtongue, foxglove penstemon).

By this time, I had been on the mesa top for five hours, and even though temperatures were mild (mid-70s) I desperately needed food and water. Mike, for his part, had also had a wildly successful day with bees, capturing many at the flowers and many more in the various pan traps (both in top and halfway up the slope). I descended the steep slope with its mixture of metal steps, cut rock, and wooden planks and enjoyed a quick feast of sardines and Triscuits (a decades-long bug-collecting-trip staple) washed down with Gatorade before getting back to work on the mesquite around the parking lot. I was committed to trying to find Agrilus on the plants—a single individual of which I’d beaten from the plants three days earlier, and after beating several plants and seeing none (but collecting a great number of clytrine and cryptocephaline chrysomelids along with other insects) I finally found one! I continued to work the trees and collect primarily chrysomelids, but no more Agrilus were seen. I am hopeful that it will be a southwestern species not currently known from Oklahoma—a situation I have found with several other Prosopis-associated beetles in this part of northwestern Oklahoma.

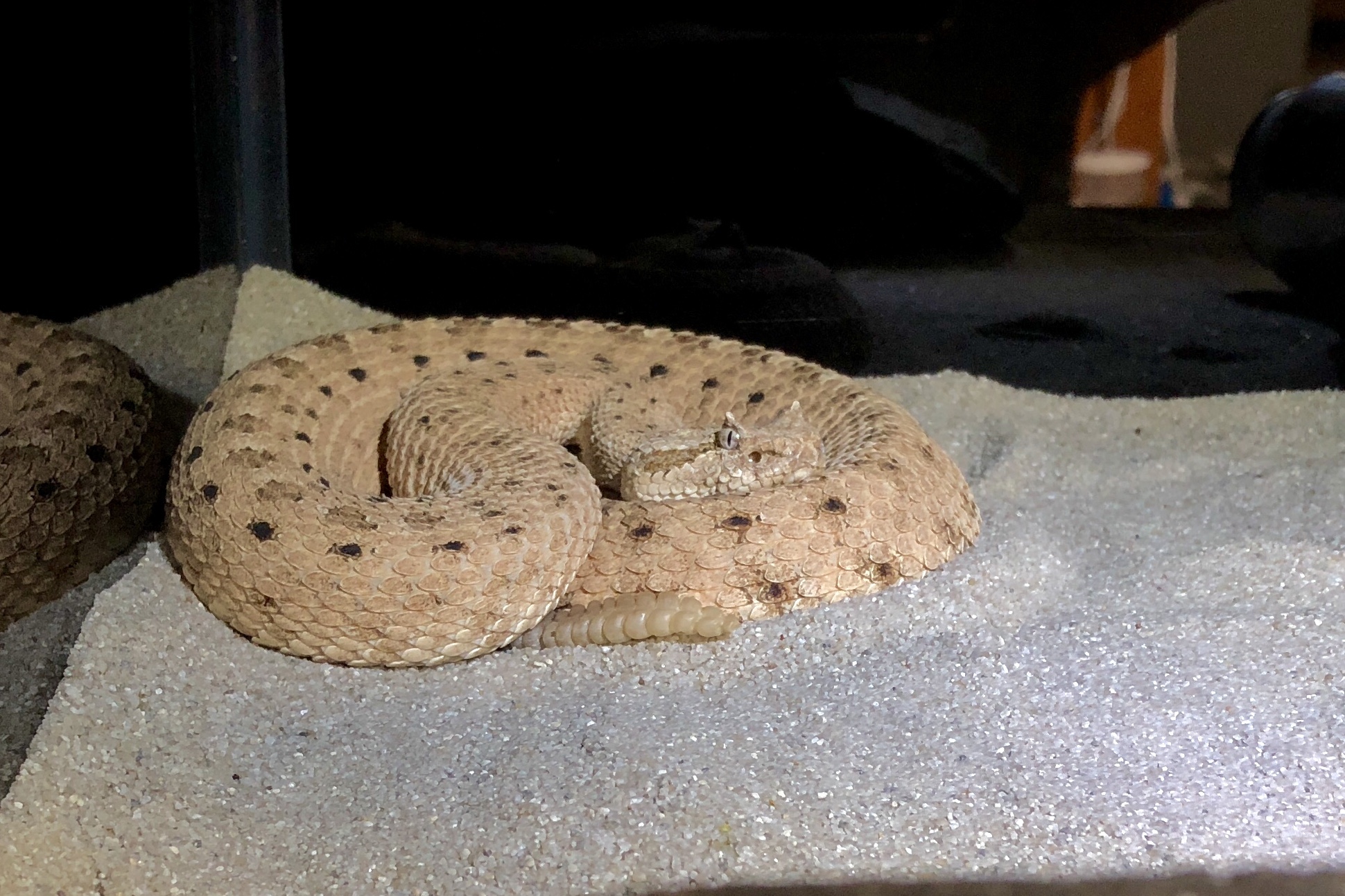

I hadn’t intended to work any additional Prosopis beyond the road into the parking lot, but there were a few particularly large trees along the front of the park next to the highway rest stop. The first one I beat yielded a very large cryptocephaline that I had not seen on any of the other Prosopis, so I continued beating them and collected a nice series along with a few other clytrines, pachybrachines, and curculionoids. At the furthest point west, I recalled having seen during a previous visit a western diamondback rattlesnake a bit further to the west, so I continued to the spot hoping to see another. No such luck, so I tiptoed through the tall grass back to safety and made my way back to the car to wrap up seven and a half hours of collecting on a spectacular day—sadly, the last of the trip!

Epilogue

This trip was just a warm-up. In just over one week, I will head out again—this time to western Texas and southern Arizona for sure, and maybe elsewhere depending on how things go. At three weeks, it will be the longest collecting trip I’ve done since I went to South Africa in 1999 and Ecuador 10 years before that. I’m also looking forward to meeting up with a number of other coleopterists at various points during the trip—Jason Hansen, Joshua Basham, and Tyler Hedlund in Texas, and Norm Woodley and Steve Lingafelter in Arizona. If there is time, I may stop off at a place or two in northeastern New Mexico and at Black Mesa on the way back. Look for an iReport on that trip sometime in early-mid June!

©️ Ted C. MacRae 2022