by Piter Kehoma Boll

Here is a list of species described this month. It certainly does not include all described species. You can see the list of Journals used in the survey of new species here.

Bacteria

- 6 new actinobacteria: Micromonoscpora acroterricola; Alloscardovia theropitheci; Kribbella jiaozuonensis; Geodermatophilus marinus; Amycolatopsis eburnea; Actinomyces lilanjuaniae;

- 8 new bacteroids: Emticicia agri; Chryseobacterium mulctrae; Confluentibacter sediminis; Allopseudarcicella aquatilis; Flavobacterium cerinum; Pontibacter arcticus; Apibacter muscae; Pedobacter helvus;

- 1 new deinococcus-thermus: Deinococcus arcticus;

- 2 new firmicutes: Lentibacillus lipolyticus; Hungateiclostridium mesophilum;

- 28 new proteobacteria: Pseudomonas juntendi; Pseudomonas nosocomialis; Pseudomonas daroniae, P. dryadis; Pseudomonas mangiferae; Shimia thalassica; Marinomonas flavescens; Thermomonas aquatica; Tabrizicola alkalilacus; Pararhodobacter marinus; Undibacterium piscinae; Actinobacillus vicugnae; Rhodosalinus halophilus; Sphingomonas gilva; Pseudomethylobacillus aquaticus; Pleionea sediminis; Bradyrhizobium niftali; Hwanghaeeella grinnelliae; Ramlibacter humi; Steroidobacter soli; Dyella amyloliquefaciens; Facilibium subflavum, Cysteiniphilum halobium; Sphingorhabdus lutea; Mycolicibacterium stellerae; Paraburkholderia pallida, P. silviterrae; Thauera lacus;

Archaeans

- 2 new species: Halostella limicola; Halorientalis pallida;

SARs

- 1 new ciliate: Neobakuella aenigmatica;

- 4 new diatoms: Catenula exigua; Prestauroneis genkalii; Cocconeis carinata; Olifantiella onnuria;

Plants

- 1 new rhodophyte: Melanothamnus maniticola;

- 4 new chlorophytes: Coelastrella thermophila, C. yingshanensis, C. tenuitheca; Microrhizoidea pickettheapsiorum;

- 1 new charophyte: Nitella megacephala;

- 1 new pteridophyte: Asplenium simaoense;

- 1 new conifer: Amentotaxus hekouensis;

- 84 new angiosperms: Gastrodia amamiana; Strobilanthes tricostata; Chamaecrista falcata; Justicia longipetiolata; Portulaca almeviae; Gastrochilus yunlongense; Polysphaeria ribauensis, P. harrisii; Echeandia jaliscensis; Prosopis andicola; Hechtia ibugana; Rhodocodon petrae, Rhodocodon viridans, Rhodocodon rubescens, Rhodocodon perrieri, R. siederi; Hemiboea thanhhoensis; Dendrobium annulatum; Euphorbia rimireptans; Polycarpaea rangaiahiana; Myrciaria alta; Astragalus admirabilus; Myrcia psammophila; Tashiroea dayaoshanensis; Petunia correntina; Brachyscome lucens, Cardamine magnifica, Ranunculus callianthus, Geranium socolateum; Connarus aureus, C. tomentosus; Calamus spp.; Gluta laosensis; Isotrema sanyaense; Bulbophyllum reflexipetalum; Ceropegia jinshaensis; Disporum nanchuanense; Gentianella macrosperma; Lysimachia fanii; Marsdenia yarlungzangboensis; Aristolochia pseudoutriformis, A. yangii; Cylindrolobus motuoensis, C. glabriflorus; Yushania tongpeii; Dendrocalamus menghanensis; Henckelia nanxiheensis, H. multinervia; Gastrochilus prionophyllus; Primula dongchuanensis; Petrocosmea rhombifolia, Petrocosmea tsaii, Didymocarpus brevipedunculatus, Henckelia xinpingensis; Pedicularis multicaulis; Spiradiclis tubiflora; Cranichis callejasii, C. roldanii, C. schultesii, C. barkleyi, C. killipii, C. juajibioyi, C. neglecta, C. pennellii, C. popayanensis, C. pseudomuscosa; Inga kursarii; Rhynchospora chapadensis, Rhynchospora harleyi; Erythroxylum niziae; Fritzschia cordifolia; Serjania rosalindae, Serjania crucensis; Waltheria saundersiae; Tarenaya longicarpa; Varronia xinguana; Justicia birae, Justicia distichophylla, Justicia mcdadeana; Oxylobus coyulensis;

Amoebozoans

- 3 new mixomycetes: Tubifera glareata, T. tomentosa, T. vanderheuliae;

- 2 new discoseans: Paramoeba aparasomata, P. karteshi;

Fungi

- 8 new ascomycetes: Plectosphaerella guizhouensis, Plectosphaerella nauculaspora; Diaporthe millettiae, Diaporthe osmanthi; Memnoniella sinensis; Kazachstania jinghongensis, Kazachstania menglunensis; Verrucoconiothyrium ambiguum;

- 18 new basidiomycetes: Marasmius albisubiculosus, M. diversus, M. elaeocephaliformis, M. laranja, M. leptocephalus, M. paratrichotus, M. segregatus; Phellodon subconfluens; Lactarius viridinigrellus; Crassisporus imbricatus, C. leucoporus, C. macroporus, C.microsporus; Camarophyllopsis olivaceogrisea, Hodophilus glaberripes; Sanghuangporus toxicodendri; Sporobolomyces agrorum, Sporobolomyces sucorum;

Poriferans

- 7 new demosponges: Hamacantha (Vomerula) mamoi, Hamacantha (Vomerula) umisachii; Megaciella cardenasi, Crella (Crella) hennequinae, Hymedesmia (Hymedesmia) noramaloneae, Clathria (Clathria) priestleyae; Racekiela cresciscrystae;

Cnidarians

- 1 new myxozoan: Myxobolus parakoi;

- 6 new anthozoan: Edwardsia alternobomen; Bunga payung, Laeta waheedae, Phenganax marumi, P. subtilis, P. stokvisi;

Flatworms

- 4 new polyclads: Stylostomum mixtomaculatum; Pseudoceros agattiensis, Pseuodoceros stellans; Anthoplana antipathellae;

- 10 new proseriates: Duplominona aduncospina, D. terdigitata, D. pusilla, D. bocasana, D. dissimilispina, D. chicomendesi, D. macrocirrus, D. diademata, D. puertoricana; Pseudominona cancan;

- 1 new triclad: Matuxia tymbyra;

Annelids

- 6 new polychaetes: Trypanosyllis mercedesae; Dendronereis chipolini, Neanthes hsinchuensis; Heteromastus namhaensis, Heteromastus gusipoensis, Heteromastus koreanus;

- 4 new clitellates: Amynthas luridus, Amynthas ruiyenensis; Decimodrilus diverticulatus, D. globulatus;

Mollusks

- 1 new bivalve: Montacutona sigalionidcola;

- 3 new gastropods: Moridilla jobeli; Sinoxychilus melanoleucus; Ganesella halabalah;

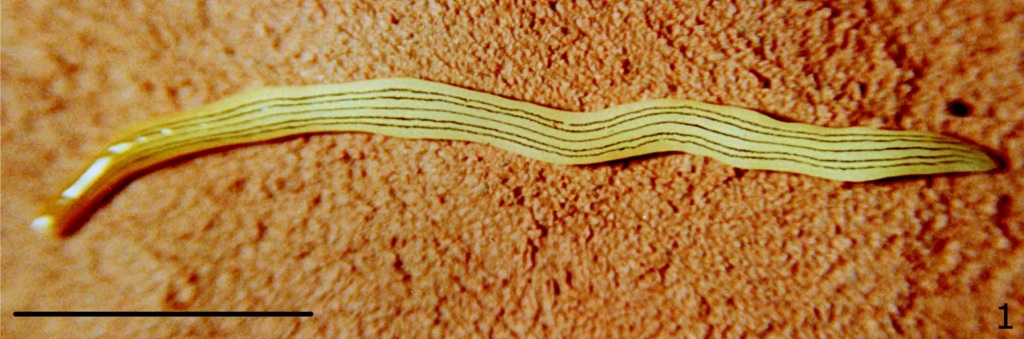

Nematodes

- 10 new species: Ditylenchus paraparvus; Aphanolaimus strilliae, Makatinus africanus; Metarhabditis giennensis; Thalassironus filiformis; Paratylencholaimus sanshaensis, Tylencholaimus zhongshanensis, Dorylaimoides shapotouensis; Philometra ostorhinchi, Philometra tenuis;

Arachnids

- 14 new mites: Lorryia meliponarum, Melissotydeus bipunctata; Kokoppia lagunaensis, Setoppia parrillarensis, Graptoppia (Stenoppia) magallanesensis; Haplozetes bayartogtokhi, Magyaria leonilae; Geckobia andina, Geckobia circumdata; Unionicola (Unionicola) maolanensis, Unionicola (Unionicola) xishuiensis, Unionicola (Unionicola) suiyangensis; Ixodes barkeri; Laelaps schatzi;

- 1 new palpigrade: Eukoenenia ibitipoca;

- 1 new scorpion: Tityus guane;

- 2 new pseudoscorpions: Parobisium magangensis, P. yuantongi;

- 27 new spiders: Buitinga qingyuani, B. wamitii, Smeringopus voi; Pholcus mixiaoqii; Onocolus ankeri; Artoria weiwei; Ochyrocera tinocoi, Ochyrocera garayae, Ochyrocera itatinga; Mago brimodes; Thaiderces shuzi, T. peterjaegeri, T. ganlan, T. ngalauindahensis, T. yangcong, T.zuichun, T. miantiao, T. jiazi, T.tuoyuan, T. fengniao, T. haima, T. chujiao, T. thamphadaengensis, T. thamprikensis; Falcileptoneta baegunsanensis, F. odaesanensis, F. umyeonsanensis;

Myriapods

- 1 new chilopod: Geophilus serbicus;

- 6 new diplopods: Hyleoglomeris hoanglien, H. fanxipan; Coloradesmus hopkinsae, C. manitou, C. beckleyi, C. warneri;

Crustaceans

- 2 new ostracods: Ilyocypris incus; Xylocythere sarrazinae;

- 1 new branchiopod: Lynceus huentelauquensis;

- 5 new copepods: Panaietis bobocephala, Panaietis flavellata; Leptotachidia senaria, L. apousia; Duoergasilus basilongus;

- 1 new cirripede: Membranobalanus porphyrophilus;

- 5 new tanaids: Hamatipeda prolata, Meromonakantha mauri, Paratyphlotanais apletos, P. bessai; Hargeria chetumalensis;

- 1 new amphipod: Ceradocus kiiensis;

- 12 new isopods: Alpioniscus lossinii, A. drazinai, A. mandalinae; Alpioniscus hirci, Alpioniscus velebiticus; Ligia dante, L. eleluensis, L. honu, L. kamehameha, L. mauinuiensis, L. pele, L. rolliensis;

- 10 new decapods: Cambarus fetzneri; Salmoneus venustus; Salmoneus durisi; Salmoneus tiburon; Alpheus perlas; Caridina malanda; Paralebbeus pegasus; Axianassa planioculus; Mediapotamon liboense;

Hexapods

- 4 new collembolans: Oligaphorura wanglangensis, O. ussurica, O. kedroviensis; Sinhomidia uniseta;

- 2 new archaeognathans: Coryphophthalmus obscurus, C. serbicus;

- 3 new odonates: Gomphidia podhigai; Dactylobasis demarmelsi; Cyclogomphus flavoannulatus;

- 3 new ephemeropterans: Camelobaetidius metae; Oligoneuriella tuberculata, Oligoneuriopsis villosus;

- 2 new dictyopterans: Quadrihormetica onorei, Lucihormetica yasuniana;

- 21 new orthopterans: Alloteratura (Alloteratura) sagittala, Alloteratura (Alloteratura) flabellata, Alloteratura (Meconemopsis) pentadactyla; Kuzicus (Kuzicus) bicurvus; Xizicus (Eoxizicus) lobicercus; Anisophya una, Xenicola taroba, Xenicola xukrixi; Criotettix zhejiangensis; Xestophrys namtseringa; Tachycines (Tachycines) huaxi; Mimicogryllus splendens, Pteroplistes bruneiensis, Tembelingiola belaitensis, Vescelia sepilokensis; Rhytidaspis arfak, R. camela, R. genyem, R. nigropunctata, R. ornata, R. variata;

- 10 new plecopterans: Perlodinella mazehaoi; Isoperla qinlinga; Hemacroneuria elongata, H. ovalis; Neoperla shiwandashana; Peltoperlopsis mengmanensis; Phanoperla zwicki; Soyedina sheldoni; Indonemoura bifida; Chrysoperla duellii;

- 1 new thysanopteran: Stictothrips farsi;

- 71 new hemipterans: Mesovelia brevia, M. dilatata, M. occulta, Mesovelia andamana, M. bispinosa, M. isiasi, M. tenuia; Rubrocuneocoris vietnamensis; Empoasca giusana, E. palgongsana; Bagauda atypicus; Calodia deergha, C. keralica, C. kumari, C. neofusca, C. periyari, C. tridenta, Glaberana acuta, G. purva, Olidiana lanceolata, O. flectheri, O. umroensis, O. unidenta, Singillatus parapectitus, S. serratispatulatus, Trinoridia dialata, T. ochrocephala, T. piperica, T. ramamurthyi, T. saraikela, T. timlivana, W. andamana, W. burmanica, Zhangolidia weicongi; Tympanoterpes virgulata, Cracenpsaltria nana, Guyalna dasyeia, Guyalna fasciata, Guyalna polypaga, Parnisa santacruzensis, Carineta ensifera, Carineta hamata, Carineta pictilis, Carineta uncinata, Herrera concolor, Herrera freiae, Herrera melanomesocranon, Herrera phyllodes, Herrera signifera; Aphis ingeborgae, Aphis conspicua, Aphis fuentesi; Tynacantha cuprea, T. umeridenigrata; Naratettix cheondungsanus; Melaniphax suffusculus; Kosmiomiris carvalhoi; Mariomella singularis; Bambusiphaga unispina; Hoplonannus bifidus, Hoplonannus robustus; Cyrta webbi; Sinonissus daozhenensis, S. hamulatus, S. longicaudus; Saissetia kunmingensis; Malingeus tumidus, Yaramayahus rufescens; Cladonota erwini; Hebetica sylviae; Calopsaltria luteotorquata;

- 47 new coleopterans: Cylloepus bispoi, C. segurae; Agonotrechus spinangulus, Sinotrechiama yunnanus; Oodescelis (Planoodescelis) lii; Tychus meggiolaroi; Incoltorrida benesculpta, I. galoko, I. magna, I. marojejy, I. quintacostata, I. zahamena, Hydroscapha andringitra; Metallactus abditus, M. chamorroi, M. dicaprioi, M. madefactus, M. praetorius, M. viator; Aenigmoronia echinodes, Australycra similis, Austronitidula multimaculata, Cychramus splendidus, Lasiodites howensis, Temnelytron nigrum; Pteroplatus luculentus; Adelopsis diabolica; Brachysomus (Hippomias) tannourinensis; Clidicus forceps, C. interfector, C. kalis, C. occisor, C. shavrini; Copelatus ankaratra, Copelatus kely, Copelatus pseudostriatus, Copelatus safiotra, Copelatus vokoka; Copelatus amphibius, Copelatus betampona, Copelatus zanatanensis, Madaglymbus kelimaso, Madaglymbus menalamba, Madaglymbus semifactus; Psiloibidion boteroi,Tropidion neisi; Xenocona antonkozlovi; Ceratochodaeus darlingi;

- 1 new megalopteran: Neochauliodes flinti;

- 43 new hymenopterans: Eucera dafnii, E. wattsi; Strumigenys caiman, S. economoi, S. hubbewatyorum, S. zemi; Kudakrumia malaenglek, Kudakrumia loaibonho, Krombeinella brothersi; Bathanthidium fengkaiense; Coryptilus circalatus, Coryptilus longicervix; Mischocyttarus nazgul, M. asahi, M. kallindusfloren; Austerocardiochiles mellosus, A. simulatus; Nylanderia bibadia, N. caerula, N. coveri, N. disatra, N. esperanza, N. fuscaspecula, N. lucayana, N. metacista, N. pini, N. semitincta, N. sierra, N. wardi, N. xestonota, N. zaminyops; Clistopyga albovittata, C. lapacensis and C. speculata; Dryinus georgianus; Bombus (Pyrobombus) interacti; Epigeiobracon perplexus; Ephutomorpha tyla; Neptihormius dipterophagus, Neptihormius whakapapa, N. herbaspicatum; Diodontus polytylus, Diodontus guichardi;

- 94 new dipterans: Leucotabanus fairchildi; Simulium (Gomphostilbia) marosense; Curtonotum abrelatas, C. irksum, C. notatum, C. prolixum, C. transitus; Maruina (Aculcina) roraimensis, Maruina (Maruina) kallyntrona, M. (M.) mystax, M. (A.) pila; Pseudoaerumnosa acinacea, P. ampliata, P. annae, P. awanensis, P. banari, P. clavidactyla, P. clivicola, P. collicola, P. consuota, P. cryptoloba, P. curvifalx, P. eminula, P. exacuta, P. filispicata, P. formosa, P. fragilis, P. impensa, P. inviolata Rudzinski, 2006, P. junciseta, P. obovata, P. pilicaudata, P. quadriquetra, P. saginata, P. tenuidens, P. tkoci; Gloma pyricornis; Chaetonerius serratus; Leinendera carrerai, Leinendera mnrj; Laneella fuscosquamata, Laneella purpurea, Mesembrinella bullata, Mesembrinella chantryi, Mesembrinella epandrioaurantia, Mesembrinella guaramacalensis, Mesembrinella longicercus, Mesembrinella mexicana, Mesembrinella nigrocoerulea, Mesembrinella serrata, Mesembrinella velasquezae, Mesembrinella violacea, Mesembrinella woodorum, Mesembrinella zurquiensis; Agromyza princei, Melanagromyza vanderlindeni, Ophiomyia antennariae, O. osmorhizae, Calycomyza smallanthi, Liriomyza euphorbiella, L. garryae, L. phloxiphaga, Phytomyza nemophilae, P. salviarum; Rhabdomastix borroloola, R. dobrotworskyi, R. dooragana, R. hirsuta, R. nivalis, R. ponticulus, R. collessiana, R. rosae; Antocha (Antocha) bella; Mycodiplosis puccinivora; Xylota hauseri, X. orientiflorum, X. xanthotarsis; Cyrtopogon hollandi, C. martini, Stenopogon graminis; Tipula (Vestiplex) butvilai; Molophilus (Molophilus) rohaceki, M. (M.) soldani; Claraeola bousynterga, C. heidiae, C. khuzestanensis, C. mantisphalliga; Cladochaeta amorimi; Polletella polleti, Polletella norrbomi, Polletella inca; Aedes (Ochlerotatus) amateuri, Aedes (Protomacleaya) lewnielseni; Neolasioptera imprimata;

- 7 new trichopterans: Rhyacophila longicaudata, Rhyacophila aksornkoaei, R. limsakuli, Rhyacophila kengtungensis; Ascotrichia adirecta, A. hystricosa, A. simoma;

- 42 new lepidopterans: Organopoda acutula, O. deltaformis, O. megiste; Herminia yuksam, H. borneo, H. amamioshima; Toccolosida nigraregina; Argyrophorus idealis, A. rubrostriata; Ancylosis larissae; Cyana lada, C. titovi; Eupoecilia jakarana, E. gedui, Lumaria phuntschona, Borneogena trashiyana,Bactra cophinana, Penthostola subnigrantis, M. brunnofasciana, Peridaedala nigrifasciana, Epiblema albulusana; Homaloxestis arcuatus, H. lactizonalis; Fujimacia cornutiprocera, F. dayaoensis, F. gracilenta, F. longispinosa; Cnephasia razowskii; Meleonoma foliiformis, M. projecta; Calisto gundlachi, Calisto siguanensis, Calisto disjunctus, Calisto sharkeyae, Calisto lastrai; Grapholita chytranthusi; Tentamen atrivirgulatum, Longistrebula argalata, Tectosquamae furvalata, Tectosquamae poguei, Tectosquamae solisae; Sufetula anania;

Echinoderms

- 2 new holothuroids: Sclerothyone reichi, Sclerothyone oloughlini;

Actinopterygians

- 2 new anguilliforms: Gymnothorax smithi; Gymnothorax andamanensis;

- 1 new aulopiform: Arctozenus australis;

- 1 new characiform: Pristella ariporo;

- 3 new cypriniforms: Garra simbalbaraensis; Neobola kinondo; Cabdio crassus;

- 2 new gobiiforms: Gymnesigobius medits; Luciogobius yubai;

- 1 new gymnotifom: Eigenmannia sirius;

- 3 new perciforms: Trachinotus macrospilus; Johnius taiwanensis; Branchiostegus biendong;

- 5 new siluriforms: Leiocassis rudicula; Chiloglanis mongoensis; Glyptothorax gopii; Synodontis denticulatus; Trichomycterus astromycterus;

Amphibians

- 17 new anurans: Cophyla fortuna; Spinomantis mirus; Ansonia kyaiktiyoensis; Pristimantis nelsongalloi; P. altillo, P. chomskyi, P. gloria, P. jimenezi, P. lutzae, P. multicolor, P. nangaritza, P. teslai, P. torresi, P. totoroi, P. verrucolatus; Noblella naturetrekii; Scinax sp.;

- 3 new caudates: Hynobius guttatus, H. tsurugiensis, H. kuishiensis;

Reptiles

- 15 new squamates: Lepidodactylus agnanus, L. dialeukos, L. zweifeli, L. mitchelli, L. kwasnickae; Helicops boitata; Cnemaspis amba, C. koynaensis; Cnemaspis aaronbaueri; Cnemaspis tanintharyi, Cnemaspis thayawthadangyi; Bothrops monsignifer; Larutia kecil; Takydromus yunkaiensis; Epictia rioignis;

– – –

* This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.