One of the most distinctive features of polychaetes are their parapodia. Parapodia are the paired “legs” of a polychaete that are outgrowths of each body segment. They can have a variety of functions and thus take on a variety of forms. The purpose of this blog post is to explore the diversity in the morphology and function of parapodia in different polychaete families.

The General Parapodium

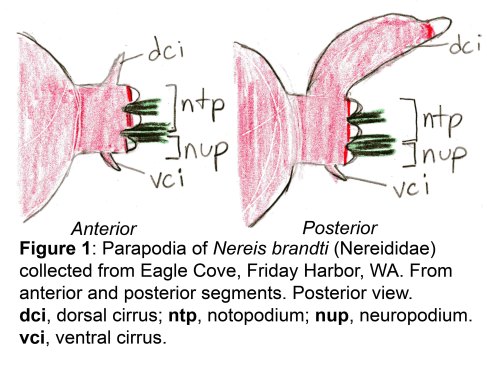

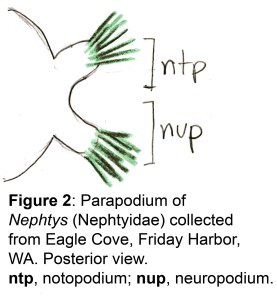

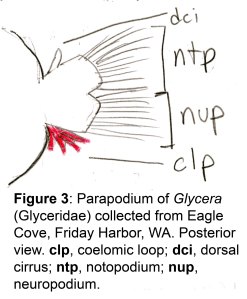

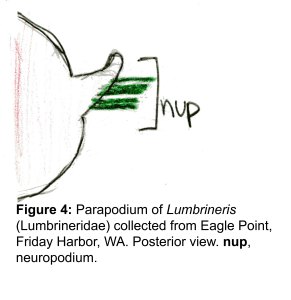

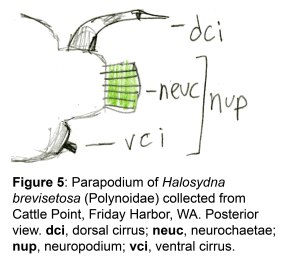

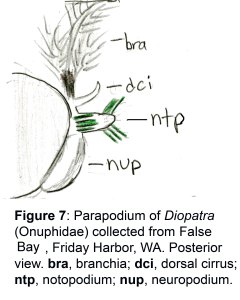

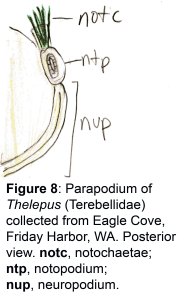

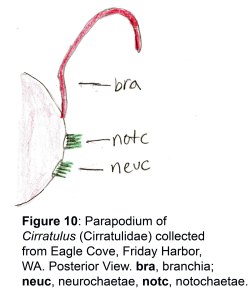

Parapodia are biramous. They have a dorsal notopodium and a ventral neuropodium. These lobes usually have chaetae (notochaetae or neurochaetae), which are bristles made of chitin and protein. The notopodium can have a dorsal outgrowth called a dorsal cirrus while the neuropodium can have a ventral cirrus. These cirri generally have sensory functions. Parapodia can also have branched outgrowths called branchia which often function as gills.

Errantia

Errantia is one of the two major groups of polychaetes. They generally have large, well-developed parapodia.

Nereididae—Nereis brandti: Parapodia are large and are used for fast crawling and swimming. The dorsal cirri get progressively larger in the posterior direction, with the posterior segments having very prominent lobe-shaped dorsal cirri. that may help with locomotion by increasing the surface area of the parapodia.

Nephtyidae—Nephtys: Parapodia are also quite large. Nephtys have rigid, muscular bodies and are active burrowers. Their large parapodia are relatively simple and facilitate movement through substrate.

Glyceridae—Glycera: Glycerids are generally carnivorous. They have elaborate burrow systems to lie in wait for prey, and presumably use their large parapodia to dig and move quickly. They have a huge eversible pharynx. I observed a red tuft that resembled branchia on the ventral side of the parapodium. However, the literature describes this tuft to be on the dorsal side. Regardless, these filamentous red structures are not true branchiae because they contain no circulatory system, which has been lost in this family. Instead, they are known as coelomic loops, and are red because the coelomic fluid that flows through it contains hemoglobin.

Lumbrineridae—Lumbrineris: These worms are long, stringy and fairly firm. They have small uniramous parapodia, with only the neuropodium present. Reduction of the notopodium occurs in several families, since the ventral neuropodium is usually more important for locomotion. Like Nephtys, they use their well-developed musculature to burrow. They are generally found in masses under rocks.

Polynoidae—Halosydna brevisetosa (the scale worm): This polychaete family has scales, called elytra, that are secreted from parts of the notopodium. This particular species have 18 pairs of elytra. Parapodia are large, with a wide bunch of chaetae on the neuropodium. The notopodium is also reduced and the dorsal cirri are present on every other parapodium. They are found sticking to the undersides of rocks.

Eunicidae—Eunice: These worms construct tubes in the sediment, from which they extend to feed. They have long branchiae for respiration. The notopodium is reduced to just the dorsal cirrus.

Onuphidae—Diopatra: These worms live in tubes that can get very deep and deoxygenated. Ours was found in a tube that was arm’s-length deep into the mud. Thus, they have very large gills anteriorly for respiration but the gills get progressively smaller down the length of the body.

Sedentaria

Sedentaria is the other major group of polychaetes. They generally have smaller, simpler parapodia than Errantia. Two major groups of these sedentary worms are Canalipalpata and Scolecida.

Canalipalpata generally live in tubes.

Terebellidae—Thelepus (the spaghetti worm): Terebellids live in tubes and stick their head tentacles out to feed. The neuropodium is a compressed, long, thick structure that extends ventrally. When the neuropodium takes this form, it is called a torus. The tori bear hook-like chaetae called uncini, while the notopodium is smaller and bears the regular, long chaetae. The uncini help anchor the worm in its tube, while the long chaetae help it to move around in the tube.

Sabellidae—Eudistylia (the feather duster worm): The thoracic and abdominal sections of this worm are distinct because of chaetal inversion. In the thorax, the notopodium has the long chaetae while in the abdomen, the neuropodium has it. The thoracic neuropodium and abdominal notopodium are tori and have uncini.

Cirratulidae—Cirratulus: The most characteristic feature of this worm are the long branchia, which function in respiration. Cirratulids live in mud or sand underneath rocks. Though they don’t have very active lifestyles, they still seem to need lots of gills. I observed they tend to tangle themselves up in their gills. The notopodium and neuropodium are reduced to just the chaetae.

Scolecida are earthworm-like polychaetes.

Arenicolidae—Abarenicola pacifica (the lugworm): These worms are deposit feeders. Because they live in burrows, oxygen can be limited so their parapodia have large branchia. Like the Lumbrineris and Nephtys, they rely on musculature to burrow. Their neuropodia are tori.

Andrea Wong

University of Washington

Cool site Thanks for being there