Minyumai Rangers

Introduction. ‘Minyumai’ is an approx. 2000ha property owned by Minyumai Landholding Aboriginal Corporation (MLHAC) and managed by the MLAC board and the Minyumai Rangers. The property is located on the far north coast of NSW, adjacent to Bundjalung National Park and Tabbimoble Nature Reserve and was dedicated as an Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) in 2011.

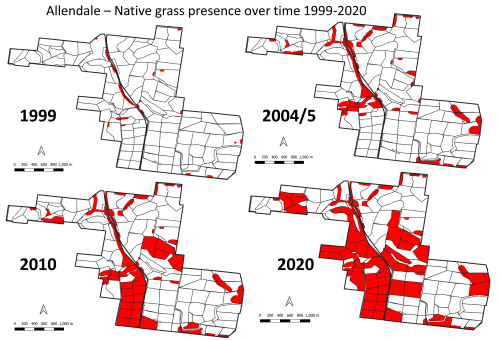

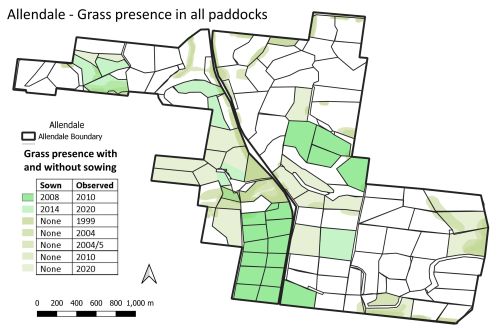

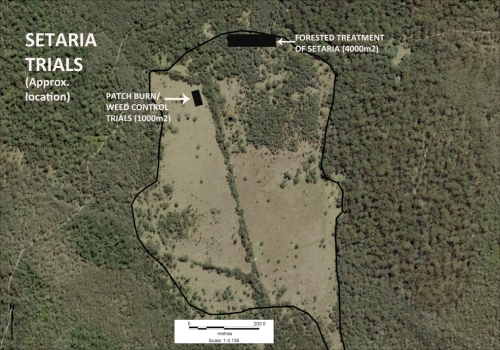

The property is largely comprised of native ecosystems, including five Endangered Ecological Communities (EECs), however it has a history of grazing in largely three sizeable clearings. The largest and most degraded of these clearings (the ‘middle clearing’) (Figs. 1 and 2) became known to the Rangers as the ‘Setaria plots’ as it was almost completely devoid of trees, was dominated by the introduced pasture grass Setaria (Setaria sphacelata) and was subsequently divided into multiple plots for treatment and monitoring.

The purpose of the work in the Setaria plots is to convert the vegetation from weed dominance to dominance by native species of the site’s prior ‘Swamp sclerophyll forest on coastal floodplains’ EEC. The project started in 2014 and is an ongoing part of the Ranger’s regular works program.

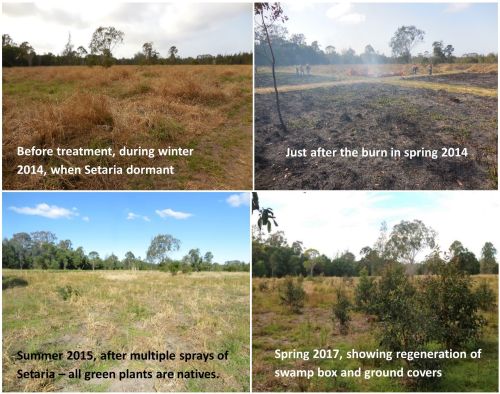

Works undertaken. After a successful trial sponsored by Firesticks in an adjacent area, a facilitated natural regeneration approach was adopted in the Setaria plots, supplemented by some tree planting. While there were little or no above-ground natives evident among the mature Setaria at the start of the project (Fig 2), the Firesticks trial showed that the use of fire followed by precision weed spraying would result in at least some regeneration of native ground covers from the soil seed bank.

The plot-by-plot approach subsequently adopted involved creating firebreaks, overspraying the mature setaria with 1% glyphosate and subsequent burning of the dried weed biomass (Figs 3 and 4). Subsequent follow-up spot-spraying was then systematically and regularly carried out.

Monitoring. The project offered an opportunity to separate and compare burn and spray treatments with spray-only treatments – i.e. all plots (except untreated controls) were subjected to systematic weed management but some were additionally burnt. Species counts and cover was measured at 2 years of age and again at 4 years of age – with the ground stratum monitored using 15 quadrats (7 burn+spray, 6 spray only and 3 controls) and woody cover monitored using 18 (20m) transects (line intercepts).

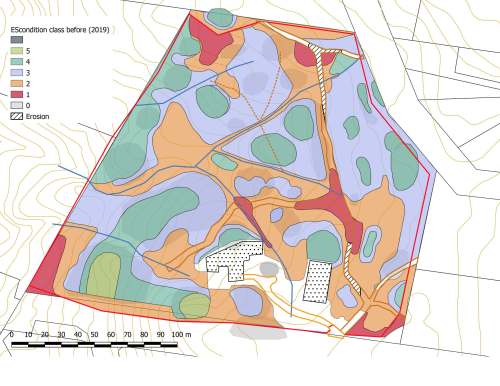

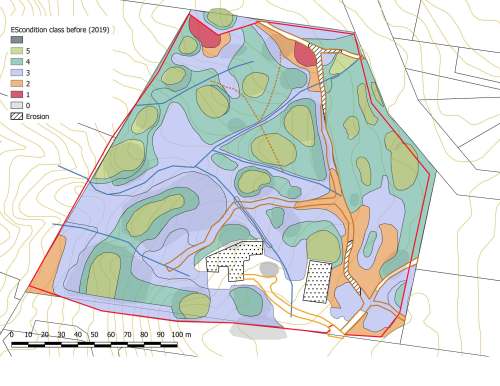

Results to date. While the initial follow up treatments revealed extensive weed, this rapidly transitioned to native dominance over time (Fig 5) and with fairly rigorous herbicide treatment of all weed by the Rangers. The site developed high levels of cover within 18 months. A total of 37 native species were recorded over the four years (including 5 trees, 2 shrubs, 1 vine, 18 forbs, 7 sedges and 4 grasses) . A total of 26 weed species (1 shrub, 14 forbs, 2 sedges and 9 grasses) occurred and while weed cover reduced over time ) most species of weed remained present in the system.

The quadrat data showed that the fire plus spot-spraying treatment resulted in improved native cover in the ground stratum (scoring an average of 3.38 on a 5 level cover scale) compared to spot-spraying alone (scoring an average of 2.17 on the 5-level cover scale) with the controls remaining in the lowest cover level.

Transect monitoring of woody species cover over time showed a significant increase in tree cover after both fire plus spray (n=5) and spray alone (n=9) treatments compared to the untreated controls (n=4) but there was no significant difference between the burn plus spray and spray only treatments, which is understandable as none of the tree species form soil seed banks.

Changes over time. The sedges, which were initially abundant in the understorey, became less abundant over the two readings. Native grasses were initially far less common but increased over time, and 10 years on are still far less prevalent than sedges, which makes sense considering the wetland nature of the site.

Some forbs, such as Buttercups (Ranunculus spp.), Gotu Kola (Centella asiatica), Pennyworts (Hydryocotyle spp.), Kidney Weed (Dichondra repens) and Native St Johns Wort (Hypericum perforatum) became frequent or abundant and remained so over the monitoring period. while other forbs such as Grass Lily (Murdannia graminea), Ludwigia (Ludwigia and Native Bluebell (Wahlenbergia sp.) remained uncommon or even rare.

Over the 10 years since the project began, the tree species Swamp Box (Lophosptemon suaveolens), Swamp Oak (Casuarina glauca) and Broad-leaved Paperbark (Melaleuca quinquinervia) have all become markedly more abundant over time through colonisation from the surrounding forest (Fig. 6) – with natural regeneration far outweighing any tree planting efforts made at the start of the project. Forest Red Gum (Eucalyptus tereticornis) did not however increase from the remnant tree on site nor did planted seedlings of this species survive.

Lessons learned and future directions. When comparing the treated areas with untreated areas it is clear that the native tree colonisaton is confined to the treated areas. Although the treated areas developed high native herbaceous cover it is likely that the open niches created by the weed control and fire allowed colonisation by trees, while the dense Setaria cover prevented regrowth.

A major challenge has been the presence of wild cattle on the property that have proved resistant to capture. This required electric fencing of the site for some years to avoid damage to plantings, although natural regeneration has now overtaken the plantings.

Critical to success was rigorous follow up prior to the weed reseeding. Complete avoidance of reseeding was not always possible due to funding limitations or personnel changes. This has resulted in some reinvasion of Setaria in some of the plots, although the Rangers continue to manage the site well.

As the mown firebreaks are still in place, there is potential for cool fire to be reintroduced into the site (followed by further weed control) should this be considered ecologically beneficial. The site may also benefit from a project (being conducted in collaboration with Nature Glenelg Trust) to fill in the artificial drain visible in Fig 1.

Stakeholders and Funding bodies. We acknowledge the valuable contributions of all the Minyumai IPA Rangers, particularly the early leadership of Minyumai Rangers, Daniel Gomes, Justin Gomes and Belinda Gomes. The Commonwealth Government’s IPA program funded the delivery of biodiversity management services by MLHAC, and funding and advice for the fire trials was provided by the NSW Nature Conservation Council’s Firesticks initiative, with advice from Oliver Costello and Richard Brittingham. Tein McDonald advised on techniques and monitoring and Andrew Johnston provided training for the Minyumai Rangers in the first years of the project.

Contact: Mary Wilson, Minyumai Land Holding Aboriginal Corporation. Email: <admin@minyumai.org.au>