English text at the bottom!

Jeg har opp gjennom årene prøvd å dyrke over 6000 spiselige planter i Malvik like øst for Trondheim. Dette har vært inspirert av Food for Free bevegelsen på 1970-tallet og i hovedsak tre hovedverker om verdens spiselige planter: Sturtevant’s Edible Plants of the World Hedrick (1919), Stephen Facciolas Cornucopia II (1998) og Plants for a Future databasen (www.pfaf.org). Dette ble en spennende reise inn i verdens mat, lokal domestisering og sanketradisjoner og jeg oppdaget etter hvert både ville vekster og prydplanter i Norge som var viktige matplanter i andre verdensdeler som var ukjent i Norge som mat. Attpåtil var de ofte godsmakende også.

Jeg skulle gjerne fortelle om disse oppdagelsene og jeg begynte derfor å skrive en serie artikler for bladet Våre Nyttevekster (senere Sopp og Nyttevekster): strutseving (2002), strandstjerne (2004), ormerot (2006), slirekne (2010). Jeg også begynte å holde et foredrag «Jorda rundt med plante som smaker» og dette ble etter hvert til en bok Around the World in 80 plants fra 2014 som handler om min topp 80 flerårige grønnsaker som jeg hadde dyrket og hvordan jeg hadde kommet frem til at flerårige grønnsaker var et bedre valg for kalde strøk, burde generelt dyrkes mer fordi de krever mindre energi og vann, binder mer karbon og er også sunnere enn tradisjonelle grønnsaker. Samtidig, takket være interessen i Middelhavsdietten har det blitt gjennomført hundrevis av etnobotaniske studier i Europa de siste 20 årene og mange nye spiselige arter er oppdaget siden min bok ble ferdig i 2013. Resultatene har vist at det har tradisjonelt vært spist over 3000 planter kun i Middelhavslandene, et enormt mangfold! Det er dette mangfoldet som karakteriserer tradisjonelle kosthold i mange land. I tillegg er det oppdaget mangfoldsretter ofte med over 50 planter villinnsamlet og dyrket. Dette ga inspirasjon til mine mangfoldsalater og min verdensrekord på 537 ingredienser i en salat fra 2004. Med økt interesse i lokal mat (både dyrket og sanket) er det flere av forfatterene av disse etnobotaniske studiene de siste årene som har foreslått dyrking av enkelte arter.

Jeg fikk lyst til å søke systematisk gjennom norsk flora på jakt etter andre spiselige planter som ikke er oppdaget enda og jeg fikk en Excel liste av alle karplanter registrert i Norge, dvs både hjemlige og fremmede arter, laget av Norsk Botanisk Forening (i 2008). Det er til sammen 4613 taksa i listen. Jeg har stort sett bare vurdert spiseligheten av arter (underarter og hybrider regnes å ha samme nytten). Det var igjen en liste over 2806 arter som er vurdert, et arbeid som har tatt 9 år å bli ferdig med (av forskjellige grunner, ikke bare arbeidsomfang som var riktignok mye større enn jeg hadde forestilt meg!). Spiseligheten av aller artene er vurdert og alle har fått en rangering på en verdiskala fra 1-5 hvor 5 er mest verdifull! Verdien i matlaging er basert på Plants for a Future databasen hvor alle plantene er rangert for spiselighet og dette er justert / supplert etter mine egne erfaringer. Når det gjelder de etterhvert mange spiselige arter som ikke er med i PFAF har jeg vurdert plantene så godt jeg kunne. Om det er snakk om planter hvor jeg ikke har erfaring selv og planten er lite brukt har den fått en verdi på 1. Det finnes en del giftige planter som er brukt etter koking / tørking (det gjelder feks smørblomstfamilien) og dette er notert ved å bruke en † symbol. NB! En del av artene er fredet og jeg på ingen måte oppfordrer til å spise feks orkideer, men etnobotaniske informasjon ER med for alle planter!

Spiseligheten er vurdert i korthet ved å notere hvilken plantedel som brukes og hvordan, feks blad eller rot i supper, salat osv. Dette er gjort først og fremst ved å sjekke Facciolas Cornucopia II, som jeg fikk av forfatteren som pdf slik at det er lett å søke. Deretter har jeg sjekket samme planten i PFAF. Om planten ikke finnes i primærdatabasene har jeg gjennomført følgende søk ved hjelp av Google Scholar: («Botaniske navn» +Edible +Ethnobotany). Siden 2018 har jeg hatt adgang til NTNUs søkesystem gjennom min gjesteforsker stilling på Ringve Botaniske Hagen. Dette har letet dette arbeidet betraktelig og gitt meg adgang til de fleste artikler jeg vil sjekke. Det er oppdaget ca 90 nye «spiselige» arter på denne måten og referansene brukt finnes nederst her. Analysen av de første 1600 (av 4613) taksa ble gjennomført uten full tilgang til litteraturen. Derfor har jeg startet fra begynnelsen igjen med fullt søk. Jeg kom igjen de første 600 taksa før jeg måtte sette sluttstreken for arbeidet. Derfor er det sikkert noen få uoppdagete spiselige arter. Jeg regner med å fullføre dette eterhvert.

Av de 2806 arter funnet en eller annen gang i norsk natur har jeg dokumentert 1242 av dem som «spist» et eller annet sted i verden, dvs 44% av alle arter registrert i Norge er «spiselige». Men, 458 eller 37% av de «spiselige» er i kategori 1 som er planter som brukes som nødmat evt planter som er sjelden brukt eller har ikke nok informasjon til å vurdere. Videre er 34% (427 arter) i kategori 2, 16% (200) i kategori 3, 7% (91) i kategori 4 og 5% (63) er i den øverste kategori.

Hele databasen er foreløpig ikke offentiggjort i påvente av hva som skal skje videre med dette.

Tabell 1 Eksempler av data fra den store norsk spiselig flora Excel ark (examples of data entries from the 2806 line Norwegian edible flora Excel sheet).

| LATIN | RANGERING (Verdiskala) († Mulig helseskadelig) | HVORDAN BRUKT? | VILL UTBREDELSES-OMRÅDET (fra Lids Norsk Flora, 2005) |

| Campanula latifolia L. | 4 | Blad (rå og kokt); Blomst (rå); Rot (rå og kokt); Se Barstow (2014) | Europa og V Asia |

| Rudbeckia laciniata L. | 3 | Ung blad og skudd (rå og kokt, tørket); Stilker (skrellet); Thayer (2017) sier at “Sochan is among the best known wild edibles of the Appalachians”. Cherokee navnet Sochan betyr “grønnsaker”. Er ikke med i Cornucopia II! Det finnes en rekke hagevarianter av denne planten! | Ø og M N Amerika |

| Scorzonera hispanica L. | 5 | Rot (kokt); Ung blad og skudd (rå og kokt); Blomsterstilker (søt; spises rå); Blomsterknopper (rå og kokt); Kronblad (i salat); se også Barstow (2014); a Norwegian article has been published recently here: http://www.edimentals.com/blog/?p=21016 | S Europa, Kaukasus, V Sibir |

| Lepidium latifolium L. | 3 | Blad (rå og kokt); Rot (brukt som pepperrot); Frø (krydder) | Europa, N Afrika til V Asia |

| Lunaria annua L. | 2 | Rot (rå); Frø (som sennep) | Europa |

| Erodium cicutarium (L.) L’Hér. | 3 | Ung blad (rå og kokt); Rot (tygget av barn) | Middelhavsområdet? |

Takk til Landbruksdirektoratet (og tidligere Genressurssenteret) som har støttet dette arbeidet gjennom prosjektet «Kartlegging – innsamling- dokumentasjon og vurdering av genetisk mangfold av spiselige planter i Norge»

References are below the English summary!

English summary: Over the years I have tried to grow over 6,000 different edible plants here in Malvik, Norway, just east of Trondheim. This has been inspired by the Food for Free movement in the 1970s and, mainly, three principal works about the world’s edible plants: Sturtevant’s Edible Plants of the World (Hedrick, 1919), Stephen Facciola’s Cornucopia II (1998) and the Plants for a Future database (www. pfaf.org). This was for me an exciting journey into the world’s food, local domestication and culinary traditions and I gradually discovered both wild plants and ornamentals here in Norway that were important food plants in other parts of the world that were unknown in Norway as food. They often tasted very good too.

I was excited to tell others about these discoveries and I therefore started writing a series of articles for the Norwegian Useful Plants Society’s magazine Våre Nyttevekster (later Sopp og Nyttevekster): ostrich fern (2002), sea aster (2004), bistort (2006), Japanese knotweed (2010). I also began to give a lecture in Norwegian with a title that literally translates as “Around the world in tasty plants” and this eventually evolved into my book Around the World in 80 plants from 2014 which is about my top 80 perennial vegetables that I have cultivated and how I had discovered that perennial vegetables were often a better choice for cold climates like mine, and that they also should generally be grown on a larger scale as they require less energy and water, bind more carbon and are also healthier than traditional vegetables (healthy both for us and the planet). At the same time, thanks to the interest in the so-called Mediterranean diet, hundreds of ethnobotanical studies have been conducted in Europe over the last 20 years and many new edible species have been discovered since my book was completed in 2013. The results have shown that there has traditionally been over 3000 plants only in Mediterranean countries, a huge diversity! It is this diversity that characterizes traditional diets in many countries. In addition, diversity dishes have been discovered often including over 50 plants collected and cultivated. This gave inspiration to my diversity salads and my world record of 537 ingredients in a salad from 2004. With increased interest in local food (both grown and harvested), several of the authors of these ethnobotanic studies have in recent years proposed cultivation of certain species.

I wanted to search systematically through the Norwegian flora in search of other edible plants that have not yet been discovered and I was given an Excel list of all vascular plants registered in Norway, i.e., both natives and introduced species, put together by the Norwegian Botanical Association (in 2008). There are a total of 4613 taxa in the list. I have basically only considered the edibility of species (subspecies and hybrids are considered to have the same use as the main species). This left a list of 2806 species that have all been evaluated, a study that has taken me 9 years to finish (for various reasons, not just the scope of work that was indeed much larger than I had imagined!). The edibility of all species is considered and each species has received a rating on a scale from 1-5 where 5 is most valuable! This is based on the Plants for a Future database (pfaf.org) where all the plants are ranked for edibility and this ranking has been adjusted / supplemented according to my own experience. When it comes to the many edible species that are not in PFAF, I have considered the value of the plants as best I could, although this is naturally quite subjective. If it is a matter of plants where I have no experience myself and the plant is little used, it is given a value of 1. There are some toxic plants that have been used traditionally after cooking / drying (for example, some members of the buttercup family) and this is noted by use of a † symbol. NB! Some of these species are rare and protected by law and I by no means encourage eating e.g., orchids, but ethnobotanic information IS given for all plants!

The edibility is assessed briefly by noting which plant part is used and how, e.g., leaf or root in soups, salad etc. This is done primarily by checking Facciola’s Cornucopia II, which I received from the author as a pdf so that it is easy to search. Then I checked the same plant in pfaf.org. If the plant is not found in the primary databases, I have performed the following keyword searches using Google Scholar: (“Botanical Name” + Edible + Ethnobotany). Since 2018 I have had access to NTNU’s (University) search system through my guest researcher position at Ringve Botanical Garden. This has made this work considerably easier and given me access to most articles I wanted to check. About 90 new “edible” species have been discovered in this way, and the references used are found at the bottom of this page. The analysis of the first 1600 (of 4613) taxa was conducted without full access to the literature. Therefore, I have started again from the beginning with the full search. I have now reanalysed the first 600 taxa before I had to finish the work. Therefore, there are probably a few undiscovered edible species.

Of the 2,806 species which have been registered at some time in Norwegian nature, I have documented 1,242 of these as “eaten” somewhere/sometime in the world, i.e., 44% of all species registered in Norway are “edible”. However, 458 or 37% of the “edibles” are in category 1 which are plants that are used as emergency food or plants that are rarely used or do not have enough information to evaluate properly. Furthermore, 34% (427 species) in category 2, 16% (200) are in category 3, 7% (91) are in category 4 and 5% (63) are in the highest category.

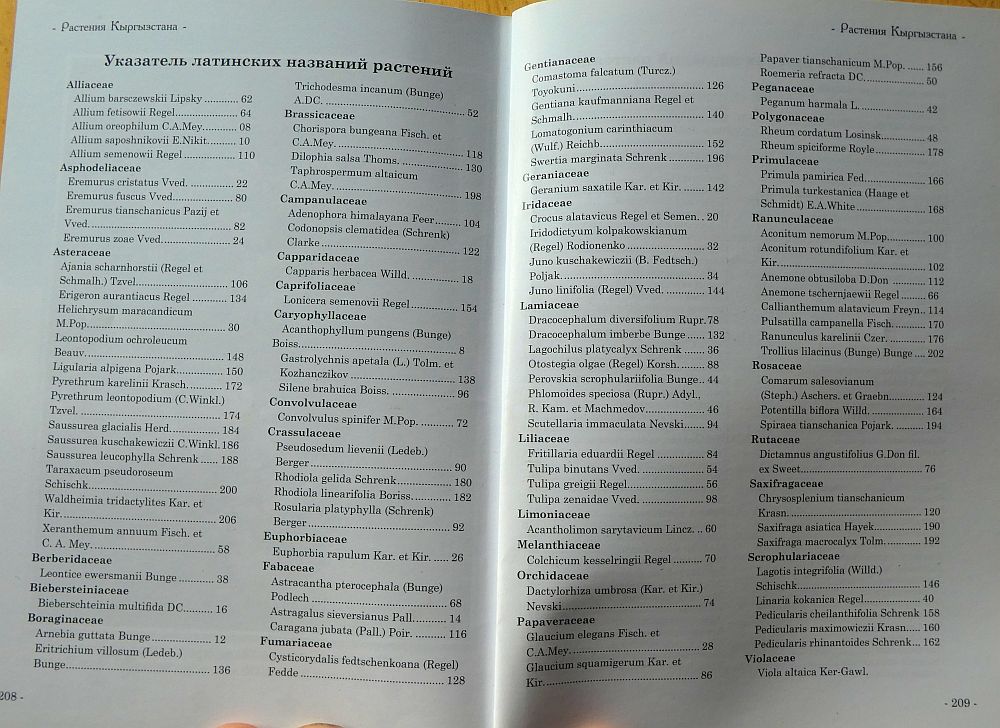

Referanser/ References

Abassi AM et al. 2015 Wild Edible Vegetables of Lesser Himalayas: Ethnobotanical and Nutraceutical Aspects, Volume 1. Springer

Abbett CP et al. 2014 Ethnobotanical survey on wild alpine food plants in Lower and Central Valais (Switzerland). J. Ethnopharmacology. 151, 624–634

Ager TA og LP Ager 1980 Ethnobotany of the Eskimos of Nelson Island, Alaska. Arctic Anthropology, 17, 26-48

Akan H et al. 2013 An ethnobotanical research of the Kalecik mountain area (Şanlıurfa, South-East Anatolia). Biological Diversity and Conservation. 6, 84-90

Aydin A et al. 2018 İkizce (Ordu-Türkiye) ilçesinde etnobotanik bir ön çalışma. Bağbahçe Bilim Dergisi. 5, 25-43

Barstow SF 2002 På leting etter strutser i det grønne. Våre Nyttevekster. 97, 2-8

Barstow SF 2004 Strandstjerne og andre spennende matplanter i fjæra. Våre Nyttevekster Nr 2, 26-40 (se http://www.edimentals.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Strandstjerne_V%C3%A5re_Nyttevekster_2014.pdf)

Barstow SF 2006 Ormerot – en tradisjonsrik vårgrønnsak og overlevelsesmat i Arktis. Sopp og nyttevekster 329-335.

Barstow SF 2010 Svartelistet godsak. Sopp og nyttevekster. 6, 22-24

Barstow SF 2014 Around the World in 80 plants. Permanent Publications

Barstow SF 2019a Spiked rampion: a perennial all season shade tolerant vegetable and one of the best edientomentals. Open source artikkel, se http://www.edimentals.com/blog/?p=21018

Barstow SF 2019b Stolt Henrik: Blad og brokkoli grønnsak, flerårig kornplante og godteri i en og samme plante. Open source artikkel, se http://www.edimentals.com/blog/?p=21016

Bautista-Cruz A et al. 2011 The traditional medicinal and food uses of four plants in Oaxaca, Mexico. J.Medicinal Plants Research. 5, 3404-3411

Benoliel D 2013 Northwest Foraging: The Classic Guide to Edible Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Skipstone Books

Bhardwaj J og MK Seth 2017 Edible wild plant resources of Bilaspur, Hamirpur and Una districts of Himachal Pradesh, India. Int. J Botany Studies. 2, 9-17

Biscotti N og A Pieroni 2015 The hidden Mediterranean diet: wild vegetables traditionally gathered and consumed in the Gargano area, Apulia, SE Italy. Soc Bot Pol 84, 327–338

Blanco-Salas J et al. 2019 Wild Plants Potentially Used in Human Food in the Protected Area “Sierra Grande de Hornachos” of Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability, 11, 456

Boesi A 2014 Traditional knowledge of wild food plants in a few Tibetan communities. J. Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 10, 75

Bowser M 2017 Handout on Edible Plants of the Kenai Peninsula

Bussmann RW et al. 2017 Ethnobotany of Samtskhe-Javakheti, Sakartvelo (Republic of Georgia), Caucasus. Indian J. Trad. Know. 16, 7-24

Çakır A 2017 Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants of Iğdır Province (East Anatolia, Turkey). Acta Soc Bot Pol. 86:3568

Çakır EA 2017 Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants of Iğdır Province (East Anatolia, Turkey) Acta Soc Bot Pol. 86, 3568.

Cansaran A og OF Kaya 2010 Contributions of the ethnobotanical ınvestigation carried out ın Amasya dıstrıct of Turkey (Amasya-Center, Bağlarüstü, Boğaköy and Vermiş villages; Yassıçal and Ziyaret towns). Biol. Diversity Conservation 3, 97-116

Cornara, L et al. 2009 Traditional uses of plants in the Eastern Riviera (Liguria, Italy). J Ethnopharmacology. 125, 16-30

Dickson C 1996 Food, medicinal and other plants from the 15th century drains of Paisley Abbey, Scotland. Veget Hist Archaeobot 5,25-31

Dénes A et al 2012 Wild plants used for food by Hungarian ethnic groups living in the Carpathian Basin. Acta Soc Bot Pol 81, 381–396

Dogan A og E Tuzlaci 2015 Wild Edible Plants of Pertek (Tunceli-Turkey). Marmara Pharmaceutical Journal 19, 126-135

Dogan Y 2012 Traditionally used wild edible greens in the Aegean Region of Turkey. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 81, 329-342

Dogan Y, S Baslar, G Ay and HH Mert 2004 The use of wild edible plants in western and central Anatolia (Turkey). Econ Bot. 58, 684–690

Ertug F 2003 Ethnobotanical Research in Friday Markets of Bodrum (Mugla, Turkey). Delpinoa 45, 167-172

Ertug F 2004 Wild Edible Plants of the Bodrum Area (Mugla, Turkey) Turk J Bot. 28, 161-174

Facciola S 1998 Cornucopia II: A Sourcebook of Edible Plants. Kampong Publications, Vista.

Gerard J 1633 The Herbal: or, general history of plants. 1975, Dover, New York

Gonzalez, JA et al. 2011 The consumption of wild and semi-domesticated edible plants in the Arribes del Duero (Salamanca-Zamora, Spain): an analysis of traditional knowledge

Guarrera PM og V Savo 2016 Wild food plants used in traditional vegetable mixtures in Italy. J. Ethnopharmacology. 185, 202–234

Hashimoto I 2003 Wild Food Lexicon, Japan. ISBN978-4-7601-3187-7

Hedrick UP 1919 Sturtevant’s Edible Plants of the World, Dover Publications, New York

Hu, S-Y 2005 Food Plants of China, Chinese University Press.

Jain A et al. 2011 Dietary Use and Conservation Concern of Edible Wetland Plants at Indo-Burma Hotspot: A Case Study from Northeast India. J. Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 7:29

Jernigan K (Red.) A Guide to the Ethnobotany of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Region

Kalle R og R Sõukand 2012 Historical ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants of Estonia (1770s–1960s). Acta Soc Bot Pol 81, 271–281

Kang Y et al. 2012 Wild food plants and wild edible fungi of Heihe valley (Qinling Mountains, Shaanxi, central China): herbophilia and indifference to fruits and mushrooms. Acta Soc Bot Pol 81, 405–413

Kang Y et al. 2013 Wild food plants and wild edible fungi in two valleys of the Qinling Mountains (Shaanxi, central China). J. Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 9, 26

Khan M 2009 Wild edible plants of Sewa catchment ara in Northwest Himalaya. J. Plant Development Sciences. 1, 1-7

Kim H og M-J Song 2013 Ethnobotanical analysis for traditional knowledge of wild edible plants in North Jeolla Province (Korea). Genet Resour Crop Evol. 60,1571–1585

Kim H-J et al. 2015 Ethnobotany of Jeju Island, Korea. Kor. J. Plant Res. 28, 217-234

Kim K-A 2012 Folk Plants in the Inland of Northern Area in Gangwon-do. Korean J. Plant Res. 25, 48-62

Kor, A et al. 2013 Wild edible plant resources used by the Mizos of Mizoram, India. Kathmandu Univ. J. Sci. Eng. Tech. 9, 106-126

Källman S 1980 A literature study that is important for the knowledge and ideas about the selection and nutrtional values of wild Swedish plants that can be used as food in emergency situations FAO Report D 54012-H2, Sweden

Ladio AH og S Morales 2013 Evaluating traditional wild edible plant knowledge among teachers of Patagonia: Patterns and prospects. Learning and Individual Differences. 27, 241-249

Lentini F and F Venza 2007 Wild food plants of popular use in Sicily. J. Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 3, 15-27

Li X-M og P-L Yang 2018 Research progress of Sonchus species. Int J Food Properties, 21, 147-157

Licata M et al. 2016 A survey of wild plant species for food use in Sicily (Italy) – results of a 3-year study in four Regional Parks J. Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 12:12

Łuczaj L 2010 Changes in the utilization of wild green vegetables in Poland since the 19th century: A comparison of four ethnobotanical surveys. J Ethnopharmacology 128, 395–404

Łuczaj L 2012 Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants of Slovakia. Acta Soc Bot Pol 81, 245-255

Łuczaj et al. 2013 Wild vegetable mixes sold in the markets of Dalmatia (southern Croatia). J. Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 9:2

Łuczaj L og A Pieroni 2016 Nutritional Ethnobotany in Europe: From Emergency Foods to Healthy Folk Cuisines and Contemporary Foraging Trends. In Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants, 35-56

MacNicol M 1967 Flower Cookery: The Art of Cooking with Flowers. Fleet Press

Malaisse F et al 2012 Ethnomycology and Ethnobotany (South Central Tibet).

Diversity, with emphasis on two underrated targets:

plants used for dyeing and incense. Geo-Eco-Trop. 6, 185-199

Manandhar NP 2002 Plants and People of Nepal, Timber Press, Portland.

Menendez-Baceta G et al. 2012 Wild edible plants traditionally gathered in Gorbeialdea (Biscay, Basque Country). Genet Resour Crop Evol. 59, 1329–1347

Moerman DE 1998 Native American Ethnobotany, Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

Moerman DE 1998 Native American Ethnobotany, Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

Mukemre M 2016 Survey of wild food plants for human consumption in villages of Catak (Van-Turkey). Indian J. Traditional Knowledge 15, 183-191

Nedelcheva A 2013 An ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Bulgaria. Eurasia J Biosci 7, 77-94

Ozbucak TB et al. 2006 The Contribution of Wild Edible Plants to Human Nutrtion in the Black Sea Region of Turkey. Ethnobotanical Leaflets 10, 98-103

Paoletti MG, AL Dreon and GG Lorenzoni 1995 Pistic. traditional food from western Friuli, N.E. Italy. Econ. Bot. 49, 26-30

Parada M 2011 Ethnobotany of food plants in the Alt Empordà region (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality 84, 11 – 25

Pascual JC og B Herrero 2017 Wild food plants gathered in the upper Pisuerga river basin, Palencia, Spain. Botany Letters, 164, 263-272

Pieroni A 1999 Gathered wild food plants in the upper valley of the Serchio River (Garfagnana), central Italy. Economic Botany 53, 327–341

Pieroni A et al. 2018 Celebrating Multi-Religious Co-Existence in Central Kurdistan: The Bio-Culturally Diverse Traditional Gathering of Wild Vegetables among Yazidis, Assyrians, and Muslim Kurds. Human Ecology, 46, 217–227

Plants for a Future (PFAF) databasen: www.pfaf.org

Polat R et al. 2015 Survey of wild food plants for human consumption in Elazig, Turkey. Indian J. Traditional Knowledge. 1, 69-75

Powell B et al. 2014 Wild leafy vegetable use and knowledge across multiple sites in Morocco: a case study for transmission of local knowledge? J. Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 10, 34

Ramachandran VS 2007 Wild edible plants of the Anamalais, Coimbatore district, western Ghats, Tamil Nadu. Ind. J. Traditional Knowledge. 6, 173-176

Ranfa A og M Bodesmo 2017 An Ethnobotanical investigation of traditional knowledge and uses of edible wild plants in the Umbria Region, Central Italy. J. Applied Botany and Food Quality. 90, 246 – 258

Redžić S og J Ferrier 2014 The Use of Wild Plants for Human Nutrition During a War: Eastern Bosnia (Western Balkans). I: Pieroni A., Quave C. (eds) Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans. Springer, New York, NY

Rendon B et al. 2001 Etnobotany of Anoda cristata. Econ. Bot. 55, 545-554

Renna M 2015 Crenate broomrape (Orobanche crenata Forskal): prospects as a food product for human nutrition. Genetic Res. Crop Evol. 62, 795-802

Senkardes I og E Tuzlaci 2016 Wild Edible Plants of Southern Part of Nevşehir in Turkey. Marmara Pharmaceutical Journal 20, 34-43

Sharma SK 1997 Studies on Kimaun Himalaya. 208ss. Indus Publishing, Kamaun, India.

Simkova K og Z Polesny 2015 Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants used in the Czech Republic. J. Applied Botany and Food Quality. 88, 49-67

Singh B 2012 Wild edible plants used by Garo tribes of Nokrek Biosphere Reserve in Meghalaya, India. Ind. J. Traditional Knowledge. 11, 166-71

Sõukand R et al. 2015 An ethnobotanical perspective on traditional fermented plant foods and beverages in Eastern Europe. J. Ethnopharmacology 170, 284–296

Sõukand R og R Kalle 2016 Changes in the Use of Wild Food Plants in Estonia 18th – 21st Century. SpringerBriefs in Plant Science.

Sõukand R og A Pieroni 2016 The importance of a border: Medical, veterinary, and wild food ethnobotany of the Hutsuls living on the Romanian and Ukrainian sides of Bukovina. J. Ethnopharmacology. 185, 17-40

Sulaini AA og SF Sabran 2018 Edible and medicinal plants sold at selected local markets in Batu Pahat, Johor, Malaysia. AIP Conference Proceedings 2002, 020006 (2018)

Svanberg I et al. 2012 Uses of tree saps in northern and eastern parts of Europe. Acta Soc Bot Pol 81, 343–357

Tardio J, M Pardo-de-Santayana og R Morales 2006 Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain. Botanical J. Linnean Soc. 152, 27–71

Tbatou M et al. 2013 Wild edible plants traditionally used in the countryside of El Jadida, coastal area in the centre of Morocco. Life Sciences Leaflets. 75, 28-48

Thayer S 2017 Incredible Wild Edibles: 36 plants that can change your life. Forager’s Harvest Press

Turner NC and MAM Bell 1971 The Ethnobotany of the Coast Salish Indians of Vancouver Island. Economic Botany. 25, 63-99

Turner NJ et al. 1992 Edible wood fern rootstocks of Western North America: Solving an Ethnobotanical Puzzle. J. Ethnobiology. 12, 1-34

Turner NJ et al. 2011 Edible and Tended Wild Plants, Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Agroecology. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 30,198-225

Uysal I et al. 2010 Ethnobotanical aspects of Kapıdağ Peninsula (Turkey). Biological Diversity and Conservation. 3, 15-22

Vitalini S et al. 2013 Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy)—An alpine ethnobotanical study J. Ethnopharmacology 145, 517–529

Wujisguleng W 2012 Ethnobotanical review of food uses of Polygonatum (Convallariaceae) in China. Acta Soc Bot Pol 81, 239–244

Özgen U et al. 2004 Ethnobotanical studies in the villages of the district of Ilica (Province Erzurum), Turkey. Economic Botany 58, 691-696