I saw my first ceiba trees in Guatemala in 1965 (as a Harvard student, working for 12 months for the Tikal archaeological project of the University of Pennsylvania museum). I was growing ceiba trees by the early 1970’s (along the entrance to my Yaxha Project camp, El Peten, while working five years to create the national park there). I continued studying Ceiba pentandra trees in the 1990’s and have increased my research on the conical spines over the last eight years. Today in 2015 I am still studying these trees: especially in the Costa Sur, Alta Verapaz, Izabal, and El Peten.

Thus it is sad to see how many web sites copy-and-paste mistaken beliefs about the Ceiba trees. Our page here is to correct a few misconceptions.

“Largely branchless” is a copy-and-paste error from people who have perhaps only seen the famous Ceiba pentandra tree of Tikal

80% of the web sites simply copy-and-paste (mis-)information from other web sites who have copied and pasted from elsewhere. To call a Ceiba pentandra tree “largely branchless” is no surprise, since 80% of the trees that grow along the tourist route have not many low branches.

But there are plenty of giant ceiba trees which have branches all up and down the truck. This is often a result of the top of the tree being injured (by lightening) so all the energy of growth remains in the lower area of the tree trunk.

If your data base is 100 ceiba trees, instead of one or two, it is easier to understand the growth patterns of Ceiba pentandra. Yes, most really tall trees have no branches, since the lower areas are in shade (caused by surrounding trees). When you see tall Ceiba trees with no branches in the middle of a cane sugar plantation, there are no branches because most were chopped off, or, this tree is 300 years old and 200 years ago it was still a jungle around it. The cane sugar clear-cutting only happened a few decades ago.

But if a ceiba tree has no other trees around it, and lots of sun everywhere, it may indeed have branches everywhere (especially if the top of the tree is injured, but I estimate this upper tree injury is not absolutely required to encourage branches all up and down the trunk).

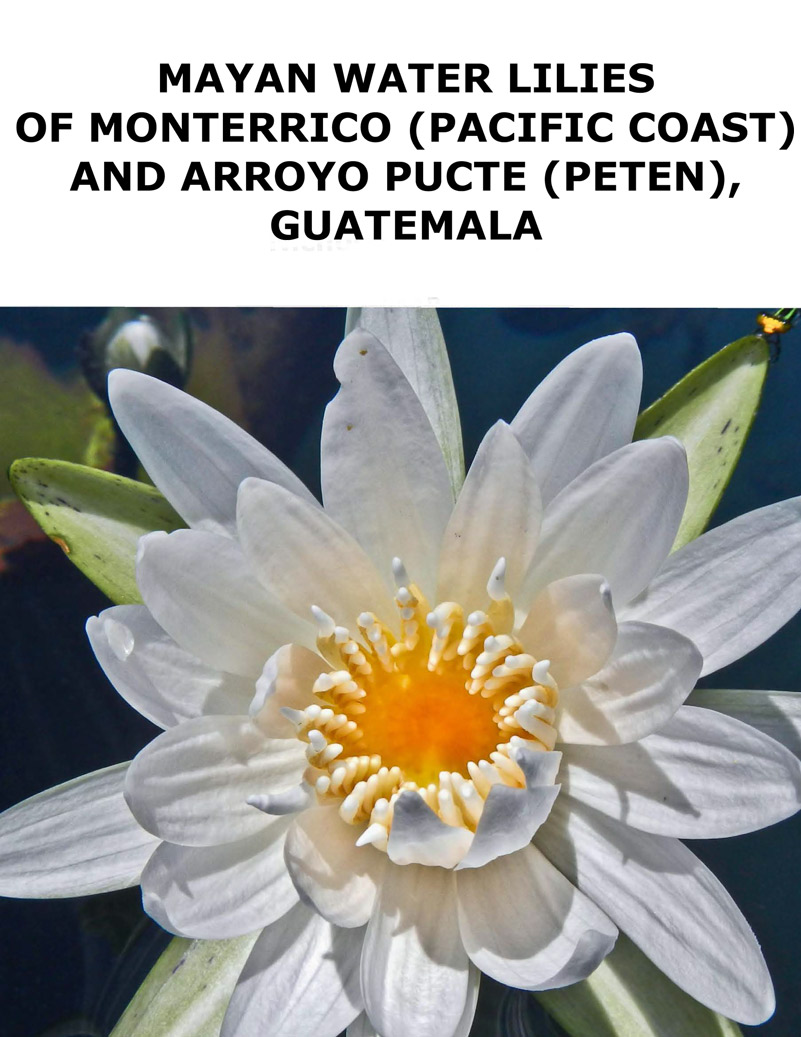

Sacred ceiba tree of life, the world tree of Maya religion and cosmology

Most civilizations of Mesoamerica show the spiny ceiba tree in their art: Mixtec, Aztec, Maya and other cultures. In most contexts it is clearly a sacred tree. There are plenty of ethnohistorical references to the ceiba tree as a giant tree upholding the world.

The roots are considered to go down into the underworld, but frankly most of the Maya area is Karst and there is not much soil, so the roots go horizontally along the surface of the ground, not way down. But in other non-karst areas the roots probably go down deep.

Spines (conical thorns) on the trunk of young ceiba trees are a major motif in Maya art

Incense burners from Lake Atitlan (Highland Guatemala) as well as funerary urns from the Quiche Highlands, and incense burners and cache vessels from Lowland Maya areas, frequently have effigies of sacred ceiba tree spikes up and down their sides. It is well known to all iconographers and most archaeologists that these spikes mimic the thorns on the trunk of young ceiba trees.

I am currently beginning a collection of ceiba bonsai, and already two totally different species of trees have been brought to me as “ceiba.” One had five leaves and obvious spines that were what I expected of the sacred ceiba of the Maya. The other “ceiba” had the swollen trunk that is also a typical feature of many of this family; but this other “ceiba” had seven leaves (and no spines, at least not yet).

Botanically the spikes are called stem emergences.

Botanists also tend to call these prickles. Sorry, but it is more realistic to call them conical spines or conical thorns.

Spanish nomenclature is very lax, such as for “zapotes,” as an example. Many completely different fruits are called zapote. For ceiba, the overall family is large, and many trees share some of the basic characteristics. But the tree that is generally considered the Maya tree of life and the national tree of Guatemala is Ceiba pentandra. It is called the kapok tree in English but almost all visitors of whatever language quickly learn to call it a ceiba.

Because the lay-person terms are so imprecise, and because even botanical names get changed, this is why FLAAR is establishing a photographic archive of all the plants, trees, flowers, fruits, etc that were sacred to the ancient Maya. I am primarily interested in species that appear in Maya murals or ceramics, or fruits which were shown as effigy vessels: cacao and guicoy are two of the most common.

More than one species of ceiba has spines: Two major species of ceiba in Guatemala

Eduardo Sacayon has pointed out to me that there are two major species of Ceiba in Guatemala; Ceiba pentandra and Ceiba aesculifolia (Pochote). The one I know best is the sacred tree of the Maya and the national tree of Guatemala, namely Ceiba pentandra.

Hura crepitans is named the “sandbox tree” in the Virgin Islands (St John, Virgin Islands, Beach Guide). But to me some of the images on Google of this tree looks like a perfect example of the Ceiba aesculifolia. Since just the trunk full of conical spines is pictured, only a botanist can tell for sure, and they normally need to see the flower. None of the Hura species that we have found in Guatemala have many spines; most Hura in Guatemala have no spines.

But there are several other trees in Guatemala that do have lots of conical spines. One is the genus of Zanthoxylum species. There will be many FLAAR Reports on “spiny trees” in future years.

COPNA, Erythrina fusca, also has spines. The reason we spend so much time on finding all the trees with spines is because Peten area Maya incensarios, some cache vessels, many later Quiche urns, and even Early Classic Teotihuacan-related Tiquisate area rectangular funerary ceramic boxes have the same conical spines (in clay). So it is suggested that iconographers cite this FLAAR web site as well as the FLAAR Reports that introduce iconographers to the actual flora and fauna that the Maya saw around them. Most of what is presented in Maya paintings and sculpture is a reflection of their natural world, from caves to specific flowers.

Not all Ceiba pentandra trees have prominent spines

Every tree species has variations. In many cases the spines simply do not exist. There is a substantial stand of Ceiba aesculifolia trees along the Rio Motagua. We have been doing photography here many times in the last five years. Most of the trees have spines, but many simply do not have spines, and not because someone has chiseled them off the trunk.

30 km away, we found a Ceiba aesculifolia with the longest spines I have yet measured, 5 cm for the longest spines on this remarkable specimen. Of course most ceiba trees, both species, have spines only one or two centimeters long; 3 cm at most (for an average tree; there are exceptions).

In other trees the lack of spines on the main truck is because they are old; so there are no more spines on the truck. But often you can see spines on the fresh young branches way up in the tree. In other instances the spines on the trunk have been knocked off so people do not scratch themselves.

If you were to photograph 20 trees with spines (as we have) there are not more than one or two that have the same pattern or size or shape of spines. I recently photographed a tree (perhaps 20 to 40 years old) that had several brown spines (but not ones that looked brown because they were sick or dying).

FLAAR Research in Maya ethnobotany, especially related to Maya iconography

| Nicholas Hellmuth showing the ceiba tree the day it was planted in the garden of FLAAR offices. |

As a comment, there are actually several other species of trees in Guatemala that also have similar spines: one of these trees has spines that are close to the same size and shape as those of the ceiba. We believe that the Maya potters and priests are imitating the spine of the Ceiba pentandra, but the other species need to be checked also, and at least added as a footnote.

|

|

|

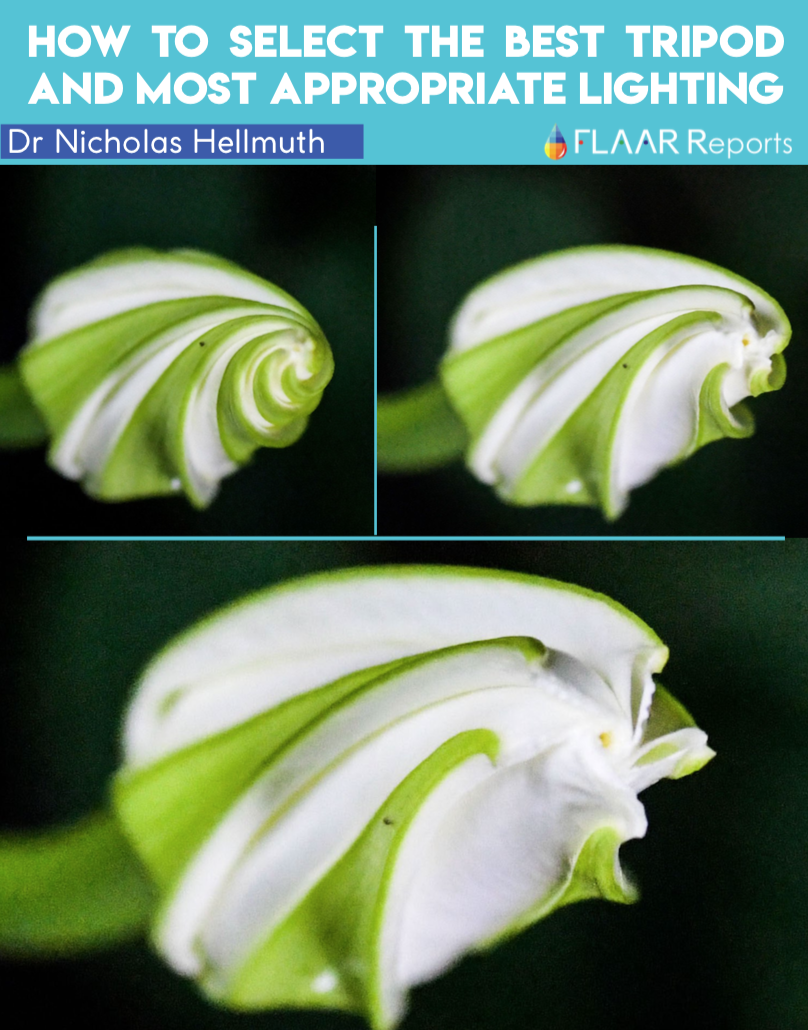

The trunk of a young ceiba tree planted in FLAAR's garden

|

There is a similar issue with identifying the “tree of Hun Hunaphu’s head” as a cacao, when the Popol Vuh clearly states it was a calabash tree (moro in local Spanish). There are actually two other trees (in addition to the cacao) which bear fruit from the trunk: the papaya and the jicara.

The jicara is a close relative of the moro. The moro is plentiful in the Departmentos of Zacapa and Chichimula; the jicara is reported to be common around Salama. Or at least this is where the artisans live that make handicrafts from the jicara. Both these trees also survive in the Peten, where you find them in gardens of local inhabitants. We have also been told that at least one of these species is common in the Costa Sur area of Guatemala.

Over and over again, statements made in books on iconography copy earlier claims. J. Eric S. Thompson claimed the Sun glyph was based on the Plumeria flower (flor de mayo). This is absurd, and probably the mistake of Thompson which more epigraphers and iconographers have repeated for decades. We have been studying Plumeria trees and flowers and, sorry, they are not the model for the sun glyph.

I have found plenty of flowers with four petals that are models for the Kin glyph: none of them are Plumeria. We even raise these 4-petaled flowers (and Plumeria) in our Mayan ethnobotanical garden around our office. My interest in 4-petaled flowers started in 1965 since the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar (Burial 196, Tikal) had several bowls and vases with 4-petaled flowers on them. Between 1965 and last year, no one that I know of had identified these flowers. Now we raise them in our garden.

FLAAR Photo Archive of Maya Ethnobotany

FLAAR is currently working on creating a photographic archive of Maya ethnobotany, especially plants, trees, and flowers that are pictured in Mayan art of the Classic Maya. Since the ceiba tree flowers only occasionally, and during the months when it’s quite hot, it is a challenge to achieve good photographs of the flowers. And since most Ceiba trees are taller than a multi-story building, it’s not easy to get close enough to their flowers to photograph them.

By irony of fate, I found a ceiba tree blooming outside my hotel during a business trip to Israel (I am a consultant to many international companies that develop and manufacture UV-cured wide-format inkjet printers). Although this was probably an African species, the trunk was identical (to me as a non-botanist) in every way, shape, and form to ceiba trees I so frequently see in Guatemala.

Since our funding is limited, we tend to be able to launch field trips primarily during December-early January, and during May-August (the times of the year I am in Guatemala). But from 2008 onward we will do our best to have some photography field trips when selected sacred flowers are blooming. Our goal is to become a preferred source of absolute top quality images of pertinent Maya plants, flowers, fruits, etc. for botanists, ethnobotanists, iconographers, epigraphers, students, authors of books and articles on these subjects, and members of the interested public.

Tzite (Palo de Pito), moro, jicaro, and Sangre de dragon (croton) are trees we also intend to study: trees that are mentioned in the Popol Vuh, trees that are sacred, and trees that produce resin for incense.

Is bark of ceiba tree an aphrodisiac ?

A web site, nationmaster, suggests an ethnomedical use of a decoction of bark of Ceiba pentandra is an aphrodisiac. Sorry, 75% of the plants and fruits claimed to be aphrodisiac are not (tomato is the best example). Aphrodisiac chemicals do exist in plants, and these plants do grow in Guatemala, but I doubt the Ceiba is one of them.

X-tabay (demon) lives in a ceiba tree

David Bolles, a linquist of Yucateco Maya, notes that xtabay: demonio maligno que, en forma de mujer, vive en el tronco de la ceiba (Ceiba pentandra). We have found fascinating documentation on the insides of 300 year old Ceiba pentandra trees and are making lists of all the zoological species which live inside Ceiba trees.

Relationship between bats and ceiba trees

A Guatemalan specialist in bats, Universidad de San Carlos, has observed that the false vampire may inhabit hollowed areas of large ceiba trees (areas that have rotted and for whatever reason are now hollow inside the otherwise living tree). He said that some of these hollow areas are large enough for a person to crawl into and stand up inside (remember that a ceiba is one of the largest trees in the Central American forest and may live several hundred years; so there is plenty of space to have a small “cave” inside that bats like to inhabit. He said there was such a hollow Ceiba in the yard of Dos Lagunas field station.

Botanical and zoological articles indicate that bats pollinate Ceiba pentandra (Gribel etai, 1999). Surely the Classic Maya would have noticed a bat as large as the false vampire coming in and out of an entrance. And clearly the Maya would have seen the bats swarming around the pretty flowers (especially since the tree has no leaves when it flowers).

We have found and photographed six enormous Ceiba pentandra trees with caves inside the trees. As soon as funding is available, we now have enough photographs from the last eight years to produce a coffee-table book to help provide visual documentation on the Ceiba tree. We have taught ourselves a lot in recent years, even by planting the seeds from the kapok puffs and growing baby ceiba trees.

Most recently updated September 28, 2015.

Checked May 25, 2010. More pictures posted June, 2010.

First posted January 2008. Updated December 2008 and August 2009.