Parkia biglobosa - Bioversity International

Parkia biglobosa - Bioversity International

Parkia biglobosa - Bioversity International

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

07<br />

Common name<br />

African locust bean (English)<br />

Néré, nété, mimosa pourpre, arbre à<br />

farine (French)<br />

■ Niéyidouba LAMIEN INERA, Centre régional<br />

de recherches environnementales et agricoles,<br />

BP 10,Koudougou, Burkina Faso<br />

■ Marius RM EKUÉ Laboratoire d’écologie<br />

appliquée, Faculté des Sciences agronomiques,<br />

Université d’Abomey-Calavi (LEA/FSA/UAC), 05 BP 993<br />

Cotonou, Bénin<br />

■ Moussa OUEDRAOGO Centre national de<br />

semences forestières (CNSF), 01 BP 2682 Ouagadougou<br />

01, Burkina Faso<br />

■ Judy LOO <strong>Bioversity</strong> <strong>International</strong>, Via dei Tre<br />

Denari, 472/a, 00057 Maccarese, Rome, Italy<br />

Conservation and Sustainable Use of Genetic Resources<br />

of Priority Food Tree Species in sub-Saharan Africa<br />

<strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong><br />

African locust bean<br />

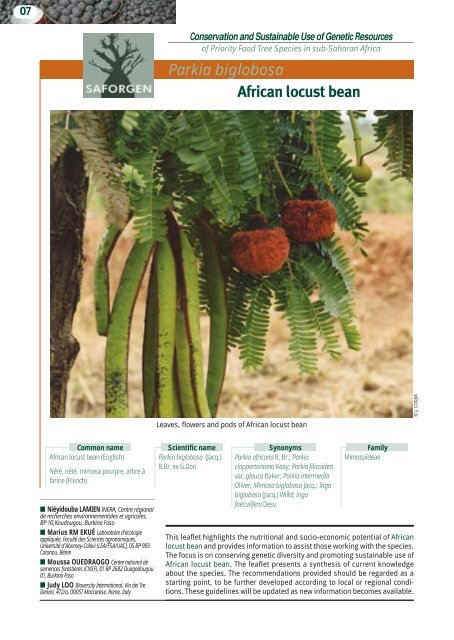

Leaves, flowers and pods of African locust bean<br />

Scientific name<br />

<strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> (Jacq.)<br />

R.Br. ex G.Don<br />

Synonyms<br />

<strong>Parkia</strong> africana R. Br.; <strong>Parkia</strong><br />

clappertoniana Keay; <strong>Parkia</strong> filicoidea<br />

var. glauca Baker; <strong>Parkia</strong> intermedia<br />

Oliver; Mimosa <strong>biglobosa</strong> Jacq.; Inga<br />

<strong>biglobosa</strong> (Jacq.) Willd; Inga<br />

faeculifera Desv.<br />

Family<br />

Mimosoïdeae<br />

This leaflet highlights the nutritional and socio-economic potential of African<br />

locust bean and provides information to assist those working with the species.<br />

The focus is on conserving genetic diversity and promoting sustainable use of<br />

African locust bean. The leaflet presents a synthesis of current knowledge<br />

about the species. The recommendations provided should be regarded as a<br />

starting point, to be further developed according to local or regional conditions.<br />

These guidelines will be updated as new information becomes available.<br />

© J. CODJIA

<strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African locust bean <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African lo<br />

02<br />

© N. LAMIEN<br />

Socio-cultural Vernacular<br />

group Country name<br />

Mossi<br />

Jula<br />

Bemoka<br />

Dagt<br />

Bambara<br />

Hausa<br />

Yoruba<br />

Ibo<br />

Djerma<br />

Kanouri<br />

Mina<br />

Fulbe<br />

Burkina Faso<br />

Burkina Faso<br />

Ghana<br />

Ghana<br />

Mali<br />

Nigeria<br />

Nigeria<br />

Nigeria<br />

Niger<br />

Niger, Nigeria<br />

and Chad<br />

Togo<br />

West Africa<br />

Geographical distribution<br />

The natural range of African locust bean covers a<br />

broad area extending from Senegal in the west to<br />

Uganda in the east and includesSudanian as well<br />

as Guineo–Congolese zones.<br />

Importance and use<br />

Zaanga<br />

Néré<br />

Du<br />

Dua<br />

Néré<br />

Dorawa<br />

Igba,<br />

Irugba-abata<br />

aridan-abata<br />

Dawadawa,<br />

nitta, nete<br />

Dosso<br />

Runo<br />

Woti<br />

Narghi<br />

The most important product is a fermented paste<br />

that is made from the dried seeds. The flowers<br />

and immature pods are eaten by children. The<br />

Soumbala from Burkina Faso, a food condiment<br />

obtained by fermentation of African locust bean seeds<br />

Distribution<br />

range of<br />

African locust<br />

bean<br />

pulp surrounding the seeds is transformed into<br />

pure dough or mixed with millet flour and eaten,<br />

especially by children on farms. The pulp and<br />

millet flour mixture is also used to produce other<br />

foods, such as couscous, porridge, a local drink,<br />

fritters and cakes.<br />

The fermented seeds are processed to make a<br />

black, highly aromatic, tasty paste that has high<br />

protein content and is used as a spice or<br />

condiment. The name varies depending on the<br />

country and local language and includes<br />

dawadawa (Nigeria), soumbala (Burkina Faso,<br />

Mali), afitin (Benin), iru (Nigeria), kinda (Sierra<br />

Leone) and nététou (Gambia). Dried fermented<br />

seeds keep for more than a year without<br />

Uses<br />

Food<br />

Fodder<br />

Fuel wood or wood<br />

production<br />

Soil protection<br />

Medicines<br />

Part of plant<br />

Flowers, pods, fruit pulp, seed<br />

Fruit, leaves<br />

Branches, stems<br />

Whole tree<br />

Flowers, fruits, leaves, bark, roots

ust bean <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African locust bean <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong><br />

© M. EKUÉ<br />

Afitin from Benin<br />

refrigeration in traditional earthenware pots.<br />

Small quantities of fermented seeds are crumbled<br />

into traditional soups and stews during cooking.<br />

Because of its savoury taste and high protein and<br />

fatcontents dawadawa is sometimes described<br />

as a meat or cheese substitute. However, it is<br />

usually eaten in small quantities. Dawadawa is<br />

also rich in vitamin B2. African locust bean<br />

probably contributes significantly to alleviating<br />

the most widespread nutritional problems in<br />

Africa, such as energy and protein deficiencies.<br />

Seeds are used as a coffee substitute. They are<br />

also embedded in a mealy pulp, sometimes<br />

called dozim that is high in energy value.<br />

The flowers and fruits are used as medicines.<br />

In addition, leaves and bark from the trunk or roots<br />

are used to treat various diseases and wounds.<br />

Fruit and leaves are also important fodder for<br />

livestock.<br />

Socio-economic value<br />

The African locust bean tree is highly valued and<br />

is commonly left standing when woodland is<br />

cleared. The trees are often individually owned.<br />

Dawadawa constitutes the main economic value<br />

for the species. It is widely eaten throughout West<br />

Africa as a diet staple, and is used in one daily<br />

meal for up to 90% of the year in some areas.<br />

Giving gifts is an important social practice and<br />

Flour from the pods<br />

Cakesfrom the pulp<br />

Seeds for sale<br />

dawadawa is one of the most appreciated<br />

culinary gifts in West Africa.<br />

The seeds and processed products are<br />

frequently traded in local markets. Some 200 000<br />

tonnes of seeds are collected every year in<br />

© N. LAMIEN<br />

© N. LAMIEN<br />

© N. LAMIEN<br />

03

<strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African locust bean <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African lo<br />

04<br />

© J. CODJIA<br />

northern Nigeria. The seeds commonly fetch two<br />

to four times as much as major staples such as<br />

maize, sorghum and millet on the market.<br />

Purchase of locust bean seed accounts for 10–20 %<br />

of regular weekly expenditures of most rural<br />

women in the Bassila region of Benin. In Burkina<br />

Faso seed sales account for up to 25% of<br />

household income.<br />

Ecology and biology<br />

<strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> tree is deciduous with a very<br />

broad crown that may reach a height of 20 m.<br />

The species grows under a wide range of<br />

conditions, where annual rainfall ranges from 600<br />

to 1500 mm and the dry season lasts 5–7 months.<br />

It occurs in natural and semi-natural habitats such<br />

as savannahs and woodlands, sometimes on<br />

rockyslopes, stony ridges and sandstone hills. It<br />

is able to withstand drought because of its deep<br />

taproot. Together with the shea butter tree<br />

(Vittelaria paradoxa), African locust bean is one of<br />

the main components of agroforestry parklands in<br />

West Africa.<br />

Reproductive biology<br />

African locust bean flowers are hermaphroditic,<br />

which means that each flower is both male and<br />

female, but the trees are largely outcrossing. This<br />

implies a degree of self-incompatibility. Flowers<br />

African locust bean tree<br />

© N. LAMIEN<br />

© N. LAMIEN<br />

are orange or red and seed pods are<br />

pink–brown to dark brown when mature, about<br />

45 cm long and 2 cm wide. They may contain up<br />

to 30 seeds embedded in a yellow fleshy pulp.<br />

Seeds have hard seed coats, are large (mean<br />

weight of 0.26 g/seed) with large cotyledons<br />

forming about 70% of their weight.<br />

Bats and some sunbirds (Nectarinidae) are<br />

reported to be important pollinators of the genus<br />

<strong>Parkia</strong>. However, in the savannah area, where<br />

bats are scarce, insects, notably bees, moths and<br />

wasps, are the main pollinators. With the long<br />

history of cultivation and use of the species<br />

across West Africa, humans are probably the<br />

main seed dispersers in many areas. Primates<br />

and small mammals are also potential seed<br />

dispersers in natural ecosystems.<br />

Phenology<br />

A link between the reproductive phase and leaf<br />

phenology has been observed. Leaves fall rapidly<br />

as increasing numbers of flowers appear and<br />

flushes of new foliage develop after flowering<br />

passes its peak. Flowering occurs near the end of<br />

the dry season, which lasts from December to April<br />

in West Africa, beginning later with increasing lati-<br />

Different stages of flowering<br />

Different stages of fruiting<br />

© N. LAMIEN © N. LAMIEN

ust bean <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African locust bean <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong><br />

tude. Spasmodic flowering sometimes occurs in<br />

other months. The availability of soil moisture<br />

seems to be a major determinant of the onset of<br />

flowering. Fruit is produced from January to May.<br />

Related species<br />

<strong>Parkia</strong> is a pantropical genus. Debates continue<br />

in the literature on the number of<br />

species but there are five well recognized<br />

species besides African locust bean: P.<br />

filicoidea, P. bicolor, P. roxburghii, P.<br />

biglandulosa and P. madagascariensis.<br />

Morphological traits<br />

and their variation<br />

African locust bean has a dark grey–brown, thick,<br />

fissured bark. Leaves are alternate, dark green<br />

and bipinnate (doubly compound). They are up to<br />

30 cm long and consist of up to 17 pairs of pinnae,<br />

with 13–60 pairs of leaflets on each. A high<br />

degree of variation has been documented in fruit<br />

production, fruit size and oil content. Trees in<br />

forests are generally taller than those in savannah<br />

areas but savannah trees have larger canopies.<br />

Genetic knowledge<br />

Genetic diversity is reported to be high, both<br />

within and among populations. On the basis of<br />

one study, the African locust bean appears to<br />

have considerably higher genetic diversity<br />

than most tropical tree species. Gene flow<br />

was estimated to be fairly low; less than two<br />

individuals on average moving between any two<br />

populations per generation. Differentiation<br />

between populations was substantial; 13% of the<br />

total diversity is estimated to be between<br />

populations and 87% is within, although the<br />

degree of differentiation between populations<br />

varies. Unpublished provenance trial results<br />

show a correlation between genetic differences<br />

and geographic distance.<br />

Gene flow between populations is facilitated<br />

by the tree’s reproductive biology, with high<br />

flowering synchronism and high level of crosspollination<br />

and the parkland systems in which<br />

the tree commonly grows.<br />

Local practices<br />

Local people in West Africa identify different<br />

‘types’ of African locust bean based on differences<br />

in morphology and fruit production. For example,<br />

people belonging to the Bariba ethnic group in<br />

north-east Benin recognize two types of African<br />

locust bean tree based on the fruiting period:<br />

trees that produce fruit early, in January, are<br />

known as dom sinkou while trees that produce<br />

fruits in March are called dom. In Burkina Faso,<br />

local people distinguish four types, according to<br />

seed size and colour: white, black, red and small<br />

seeds.<br />

Tree tenure is an important factor in determining<br />

who can harvest and process which tree products.<br />

African locust bean trees on farms, whether<br />

planted or naturally established, are generally<br />

considered to be owned by men. Women have free<br />

access only to trees in forests in spite of the fact<br />

that they play a crucial role in harvesting and processing<br />

pods and seeds and adding value to them.<br />

Threats<br />

Land and tree ownership and use<br />

The system of land and tree ownership and use<br />

policies and practices in West Africa may be a<br />

disincentive to the conservation and sustainable<br />

use of African locust bean. Women play the<br />

primary role in harvesting, processing and<br />

selling the most valuable product, dawadawa,<br />

but they do not own the trees nor can they make<br />

decisions about leaving trees standing during<br />

land clearance or conversion of parkland to other<br />

agricultural use.<br />

Climate change<br />

Successive droughts in recent years may have<br />

contributed to the observed poor regeneration of<br />

05

<strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African locust bean <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African lo<br />

06<br />

the tree. Reduction in rainfall as a result of climate<br />

change poses a threat to the species, particularly<br />

to populations in more arid regions. There have<br />

been no studies of genetic variation in tolerance<br />

to drought stress, but populations in drier areas<br />

are likely to be the most tolerant; if there is little<br />

regeneration in those areas an important genetic<br />

resource may be lost.<br />

Agricultural expansion and<br />

livestock grazing<br />

African locust bean is mainly known from<br />

parklands rather than intact forest. The trees are<br />

aging in the parklands and regeneration is low<br />

because of a variety of factors related to human<br />

population pressures. The species requires fields<br />

to lie fallow for it to regenerate, but fields are no<br />

longer being left fallow. Mechanization of farming<br />

practices, uncontrolled bush burning and<br />

increased livestock grazing all reduce habitat for<br />

the tree. When intactforestiscleared for conversion<br />

to intensive agriculture, all trees are now commonly<br />

removed, whereas in the past the practice was to<br />

leave African locust bean trees standing.<br />

Harvesting fruit and other products<br />

Excessive harvesting of fruit may be one reason<br />

for the lackof regeneration observed in parklands.<br />

Girdling is often used to increase fruit production<br />

and it may have a detrimental effect on tree<br />

survival and vigour.<br />

Conservation status<br />

African locust bean is still fairly common,<br />

especially in the semi-natural and multi-cropped<br />

agroforestry parkland systems in sub-Saharan<br />

Africa. However, according to reports, the species<br />

is declining and conservation is urgently needed.<br />

The seeds are orthodox, which means that<br />

they can be kept in long-term storage at 0-5°Cwith<br />

5% moisture content. Proper seed handling is<br />

very important, however, as seeds lose viability if<br />

the moisture content is allowed to increase above<br />

about 5%. Several seedbanks in sub-Saharan<br />

Collecting and transporting African locust bean<br />

pods in Burkina Faso<br />

Africa have ex situ collections of the species,<br />

including tree seed centres in Burkina Faso,<br />

Senegal and Togo.<br />

It is not known how many populations are<br />

protected in situ in existing parks or other<br />

protected areas.<br />

Some national institutions have established<br />

provenance trials. For example, the agricultural<br />

research institute (INERA) and the seed centre<br />

(CNSF) of Burkina Faso have trials established<br />

since 1984. Two international provenances with<br />

15 provenances from 11 African countries<br />

established by CNSF in 1995 still exist and<br />

represent unique resources, both for gene<br />

conservation and for comparative studies.<br />

Management<br />

and improvement<br />

African locust bean trees are rarely planted but are<br />

a significant component of parkland agroforestry<br />

systems because farmers preserve valuable trees<br />

when they clear new fields. The selected trees<br />

benefit from the farm husbandry and consequently<br />

grow better and produce more fruit than trees in<br />

naturalconditions. Farmers also practice girdling<br />

and branch pruning to stimulate fruit production or<br />

to reduce the negative influence of big trees on<br />

annual crops growing under their canopies.<br />

© N. LAMIEN

ust bean <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African locust bean <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong><br />

Propagation from seed<br />

Seeds can be kept for short periods in polyethylene<br />

bags at ambient temperature. The seed has a hard<br />

coat and should be soaked in concentrated<br />

sulphuric acid (98%) for three minutes, then<br />

thoroughly washed in water to increase<br />

germination. Alternatively, it should be dipped in<br />

boiling water for four seconds to soften the shell<br />

and then soaked overnight. Longer periods of<br />

treatment will damage the seeds.<br />

Vegetative propagation<br />

African locust tree can also be propagated vegetatively<br />

from rooting cuttings, air layering and<br />

tissue culture. This is an attractive option<br />

because it allows farmers to capitalise on trees<br />

with good traits and it may speed up fruit<br />

production.<br />

Guidelines for<br />

conservation and use<br />

African locust tree may be conserved through<br />

sustainable use, while ensuring that standard ex<br />

situ conservation measures are taken as a backup<br />

and in situ protection is afforded to unmanaged<br />

populations to allow them to continue to evolve<br />

under relatively natural conditions. Ex situ<br />

conservation efforts should focus on target<br />

populations in arid regions that have little or no<br />

natural regeneration. Other populations of<br />

importance are those that have been shown to<br />

have high genetic diversity or are known to have<br />

valuable characteristics for production. Data from<br />

the field trials in Burkina Faso and elsewhere<br />

should be used to guide collection of the most<br />

useful sources. Seed should be collected from at<br />

least 15 well-spaced trees in each population.<br />

Sampled populations should be distributed<br />

across a range of environments to capture<br />

potential adaptive variation. Enough seed should<br />

be collected to use in field studies in addition to<br />

quantities for long-term storage.<br />

Populations conserved in situ in protected<br />

areas may be used and conserved at the same<br />

time, depending on the regulations associated<br />

with the particular protected area.<br />

Irrespective of the regulations, sufficient fruit<br />

must be left on site to allow natural<br />

evolutionary processes to occur and trees<br />

must not be removed or girdled.<br />

It is important to ensure that women have a<br />

voice in land management to promote<br />

sustainable use and conservation. Farmers may<br />

be interested in participating in conservation<br />

projects if the revenues they derive from<br />

dawadawa and other products are considerably<br />

improved. Markets need to be developed to<br />

ensure long-term conservation and sustainable<br />

use of the species. The challenge for the<br />

establishment and maintenance of these<br />

conservation stands is how to financially support<br />

their existence for the long term. Regional and<br />

international partnership studies is indispensable<br />

to maintain such a programme.<br />

Research needs<br />

— Determine the number of viable populations in<br />

protected natural areas such as national parks<br />

— Determine genetic variation in drought<br />

tolerance and identify location of important<br />

sources of variability<br />

— Determine genetic variation in tree growth and<br />

fruit production parameters<br />

— Identify pollinator species, investigate effective<br />

pollen flow and determine threats to pollinator<br />

species<br />

— Investigate effectiveness of seed dispersal and<br />

degree of dependence on fauna that are rare or<br />

threatened<br />

— Determine effective population sizes in seminatural<br />

farmland populations and minimum<br />

viable populations for conservation and longterm<br />

sustainable use<br />

— Develop best practicesfor nursery propagation<br />

— Carry out reproductive phenology studies in<br />

different conditions. ■<br />

07

This leaflet was produced by<br />

members of the SAFORGEN Food Tree<br />

Species Working Group. The<br />

objective of the working group is to<br />

encourage collaboration among<br />

experts and researchers in order to<br />

promote sustainable use and<br />

conservation of the valuable food<br />

tree species of sub-Saharan Africa.<br />

Coordination committee:<br />

Dolores Agúndez (INIA, Spain)<br />

Oscar Eyog-Matig (<strong>Bioversity</strong> <strong>International</strong>)<br />

Niéyidouba Lamien (INERA, Burkina Faso)<br />

Lolona Ramamonjisoa (SNGF, Madagascar)<br />

Citation:<br />

Lamien N, Ekué M, Ouedraogo M and Loo J.<br />

2011.<strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong>, African locustbean.<br />

Conservation and Sustainable Use of<br />

Genetic Resources of Priority Food Tree<br />

Species in sub-Saharan Africa.<br />

<strong>Bioversity</strong> <strong>International</strong> (Rome, Italy).<br />

ISBN: 978-84-694-3166-5<br />

<strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> African locust bean<br />

Bibliography<br />

Hall JB, Tomlinson HF, Oni PI, Buche M and Aebischer DP. 1997. <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong>: a<br />

monograph. School of Agricultural and Forest Sciences, University of Wales,<br />

Bangor, UK. 107 pp.<br />

Hopkins HC. 1983. The taxonomy, reproductive biology and economic potential of<br />

<strong>Parkia</strong> (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae) in Africa and Madagascar. Botanical Journalofthe<br />

Linnean Society 87: 135–167.<br />

ICRAF. n.d. Agroforestree database [online]. Available at: http://www.worldagro<br />

forestrycentre.org/sites/treedbs/aft.asp. Accessed 17 December 2009.<br />

Lamien N and Vognan G. 2001. Importance of non-wood forest products as source<br />

of rural women’s income in western Burkina Faso. In: Pasternak D and Schlissel<br />

A, editors. Combating desertification with plants. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The<br />

Netherlands. pp. 69–79.<br />

Ouédraogo AS. 1995. <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> (Leguminosae) en Afrique de l’ouest: biosystématique<br />

et amélioration. Institut for Forestry and Nature Research, Wageningen,<br />

The Netherlands. 205 pp.<br />

Sacande M and Clethero C. 2007. <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> (Jacq.) G. Don. Seed leaflet no.<br />

124. Forest & Landscape Denmark, Hørsholm, Denmark.<br />

Schreckenberg K. 1996. Forests, fields and markets: A study of indigenous tree<br />

products in the woody savannas of the Bassila region, Benin. PhD thesis. University<br />

of London, UK. 326 pp.<br />

Sina S. 2006. Reproduction et diversité génétique chez <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> (Jacq.)<br />

G.Don. PhD thesis. Wagenigen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands. 102<br />

pp.<br />

Sina S and Traoré SA. 2002. <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> (Jacq.) R.Br. ex G.Don. [online]. Record<br />

from Protabase. Oyen LPA and Lemmens RHMJ (editors). PROTA (Plant Resources<br />

of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen,<br />

Netherlands. Available at: http://database.prota.org/search.htm.<br />

Accessed 18 December 2009.<br />

Teklehaimanot Z, Lanek J and Tomlinson HF. 1998. Provenance variation in morphology<br />

and leaflet anatomy of <strong>Parkia</strong> <strong>biglobosa</strong> and its relation to drought<br />

tolerance. Trees 13: 96–102.<br />

www.bioversityinternational.org www.inia.es www.cita-aragon.es<br />

EN