MT MABU, MOZAMBIQUE: - Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

MT MABU, MOZAMBIQUE: - Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

MT MABU, MOZAMBIQUE: - Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

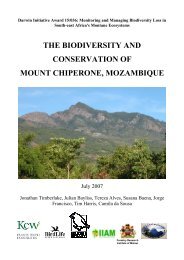

Darwin Initiative Award 15/036: Monitoring and Managing<br />

Biodiversity Loss in South-East Africa's Montane Ecosystems<br />

<strong>MT</strong> <strong>MABU</strong>, <strong>MOZAMBIQUE</strong>:<br />

BIODIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION<br />

November 2012<br />

Jonathan Timberlake, Julian Bayliss, Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire,<br />

Colin Congdon, Bill Branch, Steve Collins, Michael Curran, Robert J. Dowsett,<br />

Lincoln Fishpool, Jorge Francisco, Tim Harris, Mirjam Kopp & Camila de Sousa<br />

ABRI<br />

african butterfly research in<br />

Forestry Research<br />

Institute of Malawi

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 2<br />

Front cover: Main camp in lower forest area on Mt Mabu (JB).<br />

Frontispiece: View over Mabu forest to north (TT, top); Hermenegildo Matimele plant collecting (TT,<br />

middle L); view of Mt Mabu from abandoned tea estate (JT, middle R); butterflies (Lachnoptera ayresii)<br />

mating (JB, bottom L); Atheris mabuensis (JB, bottom R).<br />

Photo credits: JB – Julian Bayliss CS ‒ Camila de Sousa<br />

JT – Jonathan Timberlake TT – Tom Timberlake<br />

TH – Tim Harris<br />

Suggested citation: Timberlake, J.R., Bayliss, J., Dowsett-Lemaire, F.,<br />

Congdon, C., Branch, W.R., Collins, S., Curran, M., Dowsett, R.J., Fishpool,<br />

L., Francisco, J., Harris, T., Kopp, M. & de Sousa, C. (2012). Mt Mabu,<br />

Mozambique: Biodiversity and Conservation. Report produced under the<br />

Darwin Initiative Award 15/036. <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Botanic</strong> <strong>Gardens</strong>, <strong>Kew</strong>, London. 94 pp.

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 3<br />

LIST OF CONTENTS<br />

List of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3<br />

List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. 4<br />

List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 5<br />

SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 6<br />

1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 8<br />

1.1 Background .................................................................................................................... 8<br />

1.2 Media Coverage.............................................................................................................. 9<br />

2. DESCRIPTION OF STUDY AREA ................................................................................... 10<br />

2.1 Geography and Geology ............................................................................................... 10<br />

2.2 Climate ......................................................................................................................... 11<br />

2.3 Aerial Photos ................................................................................................................ 13<br />

3. HISTORY AND EARLY COLLECTING .......................................................................... 13<br />

3.1 Early History ................................................................................................................ 14<br />

3.2 Recent History .............................................................................................................. 16<br />

4. VEGETATION .. ................................................................................................................. 19<br />

4.1 Previous Studies ........................................................................................................... 19<br />

4.2 Vegetation Mapping ..................................................................................................... 19<br />

4.3 Vegetation Types .......................................................................................................... 22<br />

4.3.1 Plantations ............................................................................................................. 22<br />

4.3.2 Woodland .............................................................................................................. 22<br />

4.3.3 Moist Forest .......................................................................................................... 23<br />

4.3.4 Montane shrubland ............................................................................................... 27<br />

4.3.5 Vegetation of the Drier Western and Northern Slopes ......................................... 29<br />

4.4 Forest Plots ................................................................................................................... 29<br />

4.5 Observations on Tree Fruiting ...................................................................................... 29<br />

5. . PLANTS .............................................................................................................................. 33<br />

5.1 Previous Studies ........................................................................................................... 33<br />

5.2 Plant Collections ........................................................................................................... 33<br />

5.3 Species of Particular Interest ........................................................................................ 34<br />

6. BIRDS ................................................................................................................................. 37<br />

6.1 Previous Studies ........................................................................................................... 37<br />

6.2 Bird Survey ................................................................................................................... 37<br />

6.3 Biogeographical Significance ....................................................................................... 37<br />

6.4 Bird Species of Conservation Importance .................................................................... 39<br />

6.5 Bird Breeding Records ................................................................................................. 41<br />

7. OTHER VERTEBRATES & INVERTEBRATES ............................................................. 43<br />

7.1 Previous Studies ........................................................................................................... 43<br />

7.2 Larger Mammals .......................................................................................................... 43<br />

7.3 Bats ............................................................................................................................... 43<br />

7.4 Other Small Mammals .................................................................................................. 44<br />

7.5 Herpetofauna ................................................................................................................ 45<br />

7.6 Lepidoptera ................................................................................................................... 47<br />

7.7 Molluscs ....................................................................................................................... 49<br />

7.8 Freshwater Crustacea.................................................................................................... 49<br />

7.9 Biogeography ............................................................................................................... 50

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 4<br />

8. CONSERVATION .............................................................................................................. 51<br />

8.1 Conservation Threats .................................................................................................... 51<br />

8.2 Protection and Conservation......................................................................................... 54<br />

9. MAIN FINDINGS ............................................................................................................... 56<br />

10. RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................... 57<br />

11. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 59<br />

12. BIBLIOGRAPHY & REFERENCES ............................................................................... 60<br />

Annex 1. Participants on main Mt Mabu, October 2008 ......................................................... 66<br />

Annex 2. Media Coverage of Mt Mabu ................................................................................... 67<br />

Annex 3. Plant checklist for Mt Mabu above 800 m ............................................................... 71<br />

Annex 4. Annotated list of bird species on Mt Mabu recorded above 400 m .......................... 77<br />

Annex 5. Birds ringed near main forest camp on Mt Mabu, 16‒17 Oct 2008 ......................... 84<br />

Annex 6. List of larger mammal species recorded from the Mabu massif .............................. 85<br />

Annex 7. List of small mammal species collected or recorded from the Mabu massif ........... 87<br />

Annex 8. List of reptile and amphibian species collected or recorded from the Mabu massif 88<br />

Annex 9. Butterfly species collected on Mt Mabu from 2006 to 2010 .................................... 89<br />

LIST OF TABLES<br />

Table 1. Main visits to Mt Mabu, 2005‒2010 ............................................................................ 9<br />

Table 2. Extent of area above 1000 m by altitudinal class for the Mt Mabu massif ................ 10<br />

Table 3. Tea enterprises in the Mt Mabu area, with 1960 production figures ......................... 16<br />

Table 4. Extent of forest area by altitudinal class for the Mt Mabu massif ............................. 20<br />

Table 5. Summary of forest plot data, Mt Mabu ...................................................................... 31<br />

Table 6. Plant species of interest recorded from Mt Mabu ...................................................... 34<br />

Table 7. Species found on Mt Mabu mentioned on Sabonet Red Data lists as threatened<br />

or endemic .................................................................................................................. 36<br />

Table 8. Afromontane (near-)endemic and selected Eastern endemic bird species present<br />

on Namuli, Mulanje, Thyolo, Mabu and Chiperone Mountains ................................ 38<br />

Table 9. Location of bat sampling sites and sampling effort ................................................... 44<br />

Table 10. List of molluscs collected on Mt Mabu, 2005‒2009 ................................................ 49

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 5<br />

LIST OF FIGURES<br />

Fig. 1. Montane areas in N Mozambique studied under the Darwin Initiative project ............ 11<br />

Fig. 2. Google Earth image of Tacuane area showing Mt Mabuand roads (Aug 2006) .......... 11<br />

Fig. 3. Map of Mt Mabu area showing forest extent and main localities visited ..................... 12<br />

Fig. 4. Google Earth image of Mt Mabu massif from 2006 showing forest + dense woodland<br />

cover and abandoned tea plantations; and false-colour Landsat image from 2005 with<br />

dense vegetation cover ................................................................................................. 13<br />

Fig. 5. Map showing route of Joseph Last from Malawi to Quelimane, 1887 ......................... 15<br />

Fig. 6. Map of Zambezi Company territory (Maugham 1910) ................................................ 16<br />

Fig. 7. Base camp at abandoned tea estate manager's house, Cha Madal ................................ 17<br />

Fig. 8. Soviet map of Mt Mabu and Tacuane area, 1:250,000 scale ........................................ 18<br />

Fig. 9. Supervised classification of Mt Mabu forest vegetation, 2011 (J. Bayliss) .................. 21<br />

Fig. 10. Partially-supervised classification of Mt Mabu forest vegetation, 2008 (S. Baena) .. 21<br />

Fig. 11. Moist woodland (Syzygium cordatum) at forest margin ............................................. 23<br />

Fig. 12. Burnt woodland in agricultural zone on lower SE slopes of Mt Mabu; woodland at<br />

forest margin showing boundary ................................................................................ 23<br />

Fig. 13. Medium altitude moist forest, near Mt Mabu campsite .............................................. 25<br />

Fig. 14. Medium altitude moist forest canopy, Mt Mabu ........................................................ 25<br />

Fig. 15. Montane forest on upper slopes of Mt Mabu .............................................................. 26<br />

Fig. 16. View over montane forest on Mt Mabu ...................................................................... 27<br />

Fig. 17. Coleochloa 'grassland' on rocky slopes near summit of Mt Mabu ............................. 28<br />

Fig. 18. Upper forest margin with montane shrubland and Coleochloa 'grassland'................. 28<br />

Fig. 19. Montane shrubland near summit of Mt Mabu ............................................................ 28<br />

Fig. 20. Montane shrubland near summit of Mt Mabu ............................................................ 28<br />

Fig. 21. Cryptostephanus vansonii on upper slopes of Mt Mabu ............................................ 34<br />

Fig. 22. Polystachya songensis orchid on Mabu summit ......................................................... 34<br />

Fig. 23. Olive Sunbird in Mt Mabu forest ................................................................................ 42<br />

Fig. 24. Lesser Pouched Rat caught in medium altitude forest, Mt Mabu ............................... 45<br />

Fig. 25. Two Atheris mabuensis on forest floor ....................................................................... 46<br />

Fig. 26. Pygmy chameleon, sp. nov. ........................................................................................ 47<br />

Fig. 27. Butterfly, Papilio ophidicephalus ............................................................................... 48<br />

Fig. 28. Butterfly, Cymothoe sp. nov. ...................................................................................... 48<br />

Fig. 29. Butterfly, Baliochila sp. nov. ...................................................................................... 48<br />

Fig. 30. Woodland clearance for agriculture and fire .............................................................. 52<br />

Fig. 31. Sun squirrel caught in gin trap, Mt Mabu ................................................................... 53<br />

Fig. 32. Small mammal trap and fence, Mt Mabu .................................................................... 53<br />

Fig. 33. Small but powerful gin trap, Mabu summit ................................................................ 54<br />

Fig. 34. Large gin trap with Hassam Patel, Mabu forest .......................................................... 54<br />

Fig. 35. Villagers at Mt Mabu forest camp .............................................................................. 55

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 6<br />

SUMMARY<br />

Located in north-central Mozambique, 95 km south-east of Mt Mulanje in southern Malawi,<br />

Mt Mabu is a granitic massif rising to 1700 m. Much of it is covered in exceptionally welldeveloped<br />

and little-disturbed moist forest. It was first explored biologically in 2005 as part of<br />

a <strong>Kew</strong>-led project funded through the UK's Darwin Initiative, followed by a large expedition<br />

under the same project in 2008. Initially done with the help of Google Earth imagery,<br />

discovery of the extensive forest and the subsequent expedition gave rise to much<br />

international media coverage, some of which is outlined here. This report describes the area<br />

and its history, and outlines the main biological findings made under the project.<br />

Covering an estimated area of 7880 ha, with around 5270 ha of this at medium altitude<br />

(1000‒1400 m), the forests on Mt Mabu are some of the most extensive of this type in<br />

southern Africa. Mid-altitude forests are now increasingly rare as so many have been cleared<br />

for agriculture. In addition, Mabu's forest is also remarkably little disturbed, probably as it is<br />

mostly found on very steep and rugged terrain. Moist woodland (Syzygium cordatum,<br />

Pterocarpus angolensis, Xylopia aethiopica) and gully forest (Albizia adianthifolia,<br />

Erythrophleum suaveolens, Newtonia buchananii) are found below 1000 m, along with<br />

abandoned tea estates on the southern and south-eastern slopes. The main area of mid-altitude<br />

moist forest, perhaps the biologically richest and most important area, is characterised by<br />

large trees 40‒50 m high of Strombosia scheffleri, Newtonia buchananii, Chrysophyllum<br />

gorungosanum and Maranthes goetzeniana, with extensive clumps of the bamboo<br />

Oreobambos buchwaldii in gullies. Much moister Afromontane forest, 20‒25 m high, is<br />

found above 1350‒1400 m altitude, typically with Olea capensis, Rapanea melanophloeos,<br />

Aphloia theiformis, Faurea racemosa and Podocarpus latifolius. Emerging from the<br />

Afromontane forest at 1600‒1700 m are relatively small areas of granitic (syenite) rock with<br />

patches of montane shrubland and clumps of the sedge Coleochloa setifera, a common habitat<br />

in this region of inselbergs.<br />

Surveys carried out under the Darwin project yielded 249 plant species above 800 m<br />

altitude, of which two (a mistletoe Helixanthera schizocalyx and the shrub Vepris sp. nov.)<br />

are new to science and an additional 11 are significant range extensions from the<br />

Chimanimani Mountains or Tanzania's Southern Highlands and/or new records for<br />

Mozambique.<br />

Zoological findings of vertebrates were even more impressive with 126 bird species being<br />

recorded, including the discovery of significant populations of Cholo Alethe and the race<br />

belcheri of Green Barbet, along with smaller populations of Dapple-throat, Spotted Ground<br />

Thrush, Namuli Apalis (previously believed to be endemic to Mt Namuli) and Swynnerton's<br />

Robin. Of the 12 bat species recorded, one is new (Rhinolophus mabuensis) and two are new<br />

records for the country. A total of 15 reptile and 7 amphibian species were found, including<br />

three new species (the Mabu forest viper Atheris mabuensis, a chameleon Nadzikambia<br />

baylisii and a pygmy chameleon Rhampholeon). Two other snakes and a frog may also be<br />

new to science.

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 7<br />

Much effort went into surveying the butterflies, with 203 species on the checklist<br />

including 39 new country records. Four of these are new species (Baliochila sp. nov.,<br />

Cymothoe sp. nov., Epamera sp. nov., Leptomyrina sp. nov.) with a further three new<br />

subspecies.<br />

At present the threats to the forests of Mt Mabu are not particularly great, with the great<br />

majority of it showing very little sign of human disturbance apart from hunting/snaring for<br />

bushmeat. However, there is a notable impact on the forest‒woodland margin from fire and<br />

clearance for subsistence agriculture. Logging and clearance for commercial agriculture<br />

remain potential threats, especially with the recent marked expansion of agriculture in<br />

Mozambique and new ownership of the abandoned tea estates. At present the Mabu area is<br />

not formally protected, although there are moves to gazette it at a Provincial level and develop<br />

a conservation project through a local NGO, Justica Ambiental, and Fauna and Flora<br />

International.<br />

Twelve recommendations for both management and further research are given. At this<br />

stage it is not our technical or scientific knowledge on Mabu's biodiversity that is the limiting<br />

factor for focussed conservation action, but the development of management plans and<br />

implementation of such action on the ground. As with many forests, the forests on Mt Mabu<br />

are still able to regenerate and maintain themselves if the underlying ecological factors<br />

(rainfall, soils, regeneration microclimate and availability of propagules) remain functional.<br />

And on Mt Mabu these attributes are, at present, still healthy.

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 8<br />

1. INTRODUCTION<br />

The discovery in 2005 of a large expanse of forest on Mt Mabu in north-central Mozambique<br />

and the subsequent 2008 expedition, gave rise to much interest nationally and internationally<br />

‒ some said a "lost Eden", others called it the "Google Forest" as it was first noted using<br />

Google Earth imagery. In truth, the mountain had already been mapped and named and the<br />

forest was, of course, known to the local population. It is just that early explorers and, more<br />

recently, scientists and similar professionals had not recorded or visited it. But the large extent<br />

and relatively little-disturbed nature of the forest was indeed a very significant find, as were<br />

the number of new species found.<br />

Lying just west of the district centre of Tacuane in Zambézia Province, about 80 km southeast<br />

of the Malawi border near Mt Mulanje, Mt Mabu is one of a series of granitic blocks or<br />

inselbergs rising above the surrounding coastal lowlands. The country is sufficiently rugged<br />

that it has attracted little agriculture except on the more gentle footslopes, where tea and other<br />

plantations were established during the Portuguese colonial period.<br />

Mt Mabu and its forests had no formal protection, nor was it in any way recognised as an area<br />

worthy of conservation before this project's major expedition in October 2008. It is hoped that<br />

its now greatly increased profile will lead to sustainable conservation initiatives.<br />

1.1 Background<br />

Under a collaborative project – "Monitoring and Managing Biodiversity Loss on South-East<br />

Africa's Montane Ecosystems" funded by a UK Government Darwin Initiative grant – various<br />

trips were made to Mt Mabu area from 2005 to 2010 (Table 1), in particular a major<br />

expedition was undertaken in October 2008 (see Bayliss 2009). This was followed<br />

subsequently by a smaller trips in 2009‒2010 looking at butterflies and reptiles and for natural<br />

history filming. Most of these trips were a collaborative effort between the <strong>Royal</strong> <strong>Botanic</strong><br />

<strong>Gardens</strong> <strong>Kew</strong> (RBG <strong>Kew</strong>), the Instituto de Investigação Agraria de Moçambique (IIAM), the<br />

Maputo Natural History Museum (MHN), the Mulanje Mountain Conservation Trust<br />

(MMCT), the Forest Research Institute of Malawi (FRIM), the African Butterfly Research<br />

Institute (ABRI) in Kenya, and BirdLife International. A full list of participants on the main<br />

2008 expedition is given in Annex 1. Additional persons who contributed to sections of this<br />

report are listed in the Acknowledgements.<br />

The objectives of the study and expeditions were:<br />

1. To undertake botanical and vegetation field survey of Mt Mabu,<br />

2. To gather additional zoological information on the mountain, particularly on birds,<br />

reptiles and butterflies,<br />

3. To train a team of Mozambican and Malawian biologists in botanical and vegetation<br />

survey techniques,<br />

4. To assess the extent, status and threats to the moist forest and other biodiversity on the<br />

mountain,<br />

5. Based on gathered field data, to develop species and habitat recovery plans.<br />

This report presents and discusses findings from the main 2008 expedition, reconnaissance<br />

and subsequent trips, but also attempts to place these in a broader context as well as draw<br />

conclusions relevant to Mabu's conservation. Detailed species lists for plants, birds and<br />

butterflies are presented, along with partial data on bats, reptiles and other groups. In addition

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 9<br />

to the species lists we give the first detailed account of the vegetation, and discuss the threats<br />

to all biodiversity. Particular attention has been paid to endemic, rare or threatened species.<br />

Our main attention was given to areas and species above 800 m altitude, as below this height<br />

much of the vegetation has already been transformed.<br />

Table 1. Main visits to Mt Mabu, 2005‒2010.<br />

dates taxa recorded persons involved<br />

Dec 2005 birds, plants, herps, butterflies J. Bayliss, C. Spottiswoode, E.<br />

Herrmann, H. Patel<br />

Jan 2006 butterflies, herps J. Bayliss and others<br />

Sept-Oct 2008 herps, plants, butterflies J. Bayliss, H. Patel and others<br />

Oct 2008 plants, birds, herps, small main Darwin project expedition<br />

mammals, butterflies<br />

May 2009<br />

Oct-Nov 2010<br />

butterflies, herps<br />

butterflies, herps<br />

J. Bayliss, W. Branch, ABRI<br />

and others<br />

J. Bayliss, ABRI, FFI<br />

Nov-Dec 2010 butterflies, herps<br />

J. Bayliss, BBC filming<br />

1.2 Media Coverage<br />

Unlike other expeditions to mountains in northern Mozambique and Malawi carried out under<br />

this Darwin Initiative project, the 2008 trip to Mt Mabu gave rise to a phenomenal amount of<br />

international media attention. This coverage and interest ‒ which still continues in 2012 ‒ is<br />

outlined in Annex 2, along with a selection of references to some of the main articles and web<br />

links, including videos.

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 10<br />

2. DESCRIPTION OF STUDY AREA<br />

2.1 Geography and Geology<br />

The highest of a series of blocks, Mt Mabu rises above the surrounding lowland plains at<br />

around 350‒450 m altitude, just north of the Rio Lugela in Zambézia Province, north-central<br />

Mozambique. It is centred on 16 o 17'S, 36 o 24'E, with the 1710 m summit at 16 o 17'56.5"S,<br />

36 o 23'44.3"E. Situated within the District of Lugela, it lies some 95 km south-east of Mt<br />

Mulanje in southern Malawi, 120 km south-west of Mt Namuli and 200 km from the<br />

Provincial Capital of Quelimane on the Indian Ocean coast (Figure 1). The district centre of<br />

Lugela is 40 km away, while the larger town of Mocuba, at the confluence of the Lugela and<br />

Licungo rivers, is 85 km to the south-east.<br />

The Mabu massif is essentially a complex of granitic inselbergs ('whalebacks') or ancient<br />

igneous intrusions, exposed by millions of years of subsequent erosion. It is significantly<br />

smaller than the Namuli complex (see Timberlake et al. 2009) and, unlike that massif, does<br />

not include any substantive area of upland plateau. The rock forming the Mabu massif is<br />

syenite, similar to granite, an igneous intrusion of the younger Precambrian Namarroi series<br />

dating from 850‒1100 Mya (Instituto Nacional de Geologia 1987). This intrusion is<br />

surrounded by migmatites, also of the Namarroi series.<br />

Lugela District contains four Posto Administrativos and 16 Localidades ‒ Mabu is in the<br />

Posto Administrativo (P.A.) of Tacuane, Mabu Localidade. The nearest main administrative<br />

centre is Tacuane 15 km away (Figure 2), with the lesser administrative post of Limbuè lying<br />

on the southern footslopes of Mabu. The population of P.A. Tacuane in January 2005 was<br />

18,191 persons (Ministério da Administração Estatal 2005), a relatively low number.<br />

Population pressure is not high in this area, although the area may well have been more<br />

populous during the colonial period when the tea estates were providing employment. Areas<br />

visited by the 2008 expedition overlain by contours are shown in Figure 3.<br />

A GIS-based altitudinal analysis of the Mt Mabu area by J. Bayliss showed that out of a broad<br />

study area surrounding the Mabu massif of around 300 km 2 , 8308 ha lies above 1000 m<br />

(Table 2), which is around the lower limit of true moist forest (at least on the eastern slopes),<br />

although lowland gully forest can be found below this (see Section 4.3.3).<br />

Table 2. Extent of area above 1000 m by altitudinal class<br />

for the Mt Mabu massif.<br />

Altitude (m) extent (ha) %<br />

1000‒1200 3527 42.5<br />

1200‒1400 3723 44.8<br />

1400‒1600 1031 12.4<br />

1600+ 27 0.3<br />

Total 8308 100.0<br />

Although the forest on Mt Mabu was first noted on Google Earth (Figure 4a), and has<br />

sometimes been called the "Google Forest", there are some inaccuracies present on the<br />

webpage images (accessed January 2012). The main one is that the peak of Mt Mabu is<br />

shown on Google Earth as being 18 km east of its actual location ‒ the peak shown as "Mt<br />

Mabu" is a wooded area away from the main massif. Secondly, on the ground it is clear that<br />

the peak is along a bare open ridge south-west of the main rock outcrop, but the highest point<br />

appearing on Google Earth imagery is 1651 m, not 1710 m as on all cadastral maps, and is

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 11<br />

apparently situated on a vegetated lower ledge some 600 m to the south-east. This could be an<br />

artefact resulting from cloud cover.<br />

Fig. 1. Montane areas in N Mozambique studied<br />

under the Darwin Initiative project [JB].<br />

Fig. 2. Google Earth image of Tacuane area showing Mt Mabu (centre left) and roads (Aug 2006)[JF].<br />

2.2 Climate<br />

Climate data from the Mabu massif itself above 1000 m altitude are not available, but data for<br />

the Madal tea estates near Tacuane (16 o 21'S, 36 o 22'E, 400 m altitude), possibly at Limbuè just

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 12<br />

7 km away, is summarised in Kassam et al. (1981). These data are for only 16 years and<br />

probably date from the mid-1960s.<br />

Mean annual rainfall is given as 2119.1 mm, ranging from a monthly mean of 34.2 mm in<br />

September to 362.3 mm in January. The main rainfall months are November to April (1793.1<br />

mm over 6 months or 84.6% of annual total), while the four months from December to March<br />

have a mean of 1410.9 mm (66.6% of total). Over the 16 years recorded the wettest months<br />

were March (mean 381.1 mm) and January (mean 362.3 mm).<br />

Mean annual temperature was 23.7 o C, ranging from 21.0 in July to 25.5 o C in October. The<br />

mean maximum of 32.9 o C was in October with a mean minimum of 14.9 o C in July. Unlike<br />

the situation on Mt Namuli (Timberlake et al. 2009), the occurrence of frost is likely to be<br />

rare. Evapotranspiration (Penman) was 1252.6 mm/year ranging from 63.7 mm in June to<br />

142.5 in October. During the cooler winter months potential evapotranspiration is roughly<br />

equivalent to rainfall, but in October it is more than three times monthly rainfall.<br />

According to Reddy (1984) in his overview of Mozambique's climate, rainfall in the area<br />

should be around 1500 mm/year (surprisingly less than shown by actual rainfall records) with<br />

a low variation of only 20%. The winter rainfall index (30) indicates that some winter<br />

cropping is possible. In a national context the Cha Madal area is a relatively high rainfall area<br />

similar to Mt Namuli (zone 1‒2a, moderately cool; national climatic resources inventory,<br />

Voortman & Spiers 1982), with the possibility of two rainfed growing periods in 10% of<br />

years, perhaps with a 300 day growing period each year.<br />

Fig. 3. Map of Mt Mabu area showing forest extent and main localities visited (Oct 2008)[JB].

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 13<br />

2.3 Aerial Photos<br />

The only aerial photos apparently available are from August 1965 and June 1969 at a given<br />

scale of around 1:43,000, although subsequent analysis and measurements from the 1:50,000<br />

map sheet suggest the scale is actually around 1:35,000. Owing to distortion, all area<br />

determinations were made using satellite imagery.<br />

Aerial photos of Mt Mabu, ±1:43,000 scale:<br />

row 418/062‒072 (north), 17 August 1965<br />

row 3111/076‒086 (mid), 15 June 1969<br />

row 418/118‒111 (south), 17 August 1965<br />

Fig. 4a,b. Google Earth image of Mt Mabu massif from 2006 (left) showing forest + dense woodland<br />

cover in dense green and abandoned tea plantations in paler blue-green (lower right and lower centre,<br />

with straight lines) and false-colour Landsat image (right) from July 2005 with dense vegetation cover<br />

shown in red.

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 14<br />

3. HISTORY AND EARLY COLLECTING<br />

3.1 Early History<br />

We have not been able to find any reports of early colonial explorers noting or visiting the<br />

Mabu massif, at least in the British sources that describe the exploration of Mt Namuli and<br />

travels across northern Mozambique to southern Malawi in the latter 19 th and first half of the<br />

20 th century (e.g. Johnson 1884, O'Neill 1884, Last 1887, Vincent 1933a).<br />

Joseph Last, an intrepid 19th Century British traveller, carried out a lengthy journey in 1885‒<br />

1887 from the southern Tanzania coast to Blantyre in what is now Malawi, around parts of<br />

southern Malawi and then down to the coast at Quelimane and back to Blantyre (Last 1887,<br />

1890, Timberlake et al. 2009). Part of this long trip involved a foot safari from Mt Namuli<br />

down along the Rio Licungo to the coast and then, in mid-December 1886 after a few days<br />

rest in Quelimane, upstream along the Rio Licungo to what is now Mocuba, along the Rio<br />

Lugela and through the hilly country north of Lugela town to what is now Namarroi. From<br />

there he walked along the Rio Luo entering Malawi just south of Lake Chilwa (Chirwa) and<br />

north of Mt Mulanje, arriving in Blantyre on 14 January 1887. Unfortunately, in the account<br />

published by his sponsors, the <strong>Royal</strong> Geographical Society (Last 1887), he hardly mentions<br />

the Lugela leg of this trip. The route he took is shown on a subsequent map (Last 1890,<br />

portion shown in Figure 5). However, despite attempts to match the Lugela portion with<br />

present 1:250,000 and 1:50,000 map sheets, his route could not be traced except in fairly<br />

broad terms.<br />

All that can be said is that Last left the Rio Lugela heading north upstream of present-day<br />

Mocuba (not marked on his map) somewhere between Mt Cuba/Murra (16 o 40'S, 36 o 50'E) and<br />

just upstream of the Xilusi‒Lugela confluence (16 o 32'S, 36 o 38'E). From there he made his<br />

way between the hills west of Mt Mavigue ("Mavugwe", 16 o 22'S, 36 o 45'E), passing east of<br />

what is now Muabana but west of Mt Muiane ("Mwiani",16 o 02'S, 36 o 37'E), and then crossing<br />

the present-day Rio Mucodi soon after, some 30 km west of Namarroi, before travelling along<br />

the Rio Luo. Thereafter he followed the Luo westwards towards Malawi, which he entered<br />

just south of Lake Chilwa (Chirwa).<br />

In those days, fixing longitude was not easily done and distances were estimated from time<br />

spent walking, so many distortions are apparent in the 1890 map (Figure 5). Thus it has not<br />

been possible to identify more than a very few of the hills or other points it shows, and the<br />

relative positions of peaks seem highly distorted compared to present-day maps. However,<br />

although it seems fairly certain that of the early recorded travellers Last perhaps came closest,<br />

he did not pass close to Mt Mabu or see it (despite an intriguingly-named peak "Mapu<br />

H"[hill] on his 1890 map), or travel along the route of the present-day Tacuane‒Muabana<br />

road. Unfortunately, in his account there is also no mention of the type of country he passed<br />

through, the people or the life in these areas, or even whom he went with.<br />

Earlier, in 1884, Daniel Rankin and H.E. O'Neill (then the British Consul on Mozambique<br />

Island) plus 23 porters, walked from Blantyre to Quelimane along an existing and significant<br />

trade route to see how quick and effective that route was to the coast (Rankin 1885). It took<br />

them just 39 days. At the time there was concern that the Rio Zambezi was becoming less<br />

passable to boats owing to river silting, and that this route into the important new settlements<br />

of Blantyre and Zomba in southern Malawi could be easily cut by hostile forces. Their route<br />

passed south of the Mulanje massif, across the headwaters of the Rio Lugela but kept to<br />

higher ground until it met the Rio Tetema. From here it followed the river down to the<br />

Munguze ("Mulongusi") confluence and then down the Rio Licuare ("Likwati") to<br />

Quelimane. However, this route, also shown on Last's map (Last 1990), passes quite a long<br />

way south of Mt Mabu.

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 15<br />

Fig. 5. Map showing route of Joseph<br />

Last from Malawi to Quelimane,<br />

1887.<br />

Another book by an early traveller (Maugham 1910) on the whole Zambezia area does not<br />

mention Mabu or the area around, focussing more on the coastal strip. Although the Namuli<br />

area is clearly shown on his map, the Mabu area is almost omitted (Figure 6).<br />

Hence despite a significant amount of trading and travelling in this part of north-central<br />

Mozambique, it appears that the Mabu area was continually by-passed, perhaps because of its<br />

rugged terrain, poor agricultural potential, thus scattered and low human population.

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 16<br />

Fig. 6. Map of Zambezi Company territory (from Maugham 1910).<br />

3.2 Recent History<br />

The first major economic development in the area appears to have been the establishment of<br />

tea plantations in what was then Tacuane District on the lower slopes of Mt Mabu in the<br />

1930s (Wilson, Smithett & Co. 1962). By 1961 there were three tea estates in the area and<br />

two tea factories, compared to 14 estates and 11 factories in the Gurué area around Mt Namuli<br />

and 7 estates and 3 factories in the Milange area just across the border from Mt Mulanje in<br />

Malawi. Details of the three Tacuane estates are given in Table 3. From these records it<br />

appears that the estate where the present Darwin expedition was initially based ‒ Cha Madal ‒<br />

was by far the largest.<br />

Table 3. Tea enterprises in the Mt Mabu area, with 1960 production figures<br />

(from Wilson, Smithett & Co. 1962).<br />

Company<br />

altitude<br />

(m)<br />

Company<br />

area under<br />

tea (ha)<br />

tea production<br />

(kg)<br />

Cha Madal 400 Sociedade Agricola do Madal 607.5 444,466<br />

Cha Tacuane 700 Manuel Nunes 342.2 182,217<br />

Cha Lugela 700 João Martins 93.2 (no factory)<br />

1042.9 626,683<br />

The area under tea in northern Mozambique in the 1960s was surprisingly large at 15,010 ha,<br />

greater than that in Malawi (12,110 ha) or Kenya (14,950 ha). Mozambique's total tea<br />

production in 1961 was 23,368,000 lbs [pounds] (10,609,072 kg), with exports being<br />

21,362,000 lbs (9,698,348 kg), compared to production of 31,518,000 lbs (14,309,172 kg) in<br />

Nyasaland [Malawi], 27,869,000 lbs in Kenya, 9,830,000 lbs in Tanganyika [Tanzania] and<br />

2,379,000 lbs in Southern Rhodesia [Zimbabwe]. Hence production per hectare in<br />

Mozambique at 706.9 kg/ha was significantly less than that in Malawi (1182 kg/ha) or Kenya<br />

(847 kg/ha) (all figures from Wilson, Smithett & Co. 1962). Tea production was obviously a

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 17<br />

major economic and agricultural activity in the area in the 1960s, but probably declined<br />

significantly in the 1970s with the Independence struggle and subsequent civil war.<br />

At the base of Mt Mabu on the southeastern side is the now-derelict Cha Madal Tea Estate,<br />

until recently owned by Madal (now Rift Valley Holdings), a large Mozambican company<br />

best known for its coconut plantations on the coast near Quelimane. In 1961 the estate<br />

manager was John Edge (Wilson, Smithett & Co. 1962). It was obviously a large estate, with<br />

an extensive factory, out-buildings, workers' and managers' housing. What was presumably<br />

the Estate Manager's house (16°18'20.5"S, 36°25'28.8"E, Figure 7a,b) was a large, spreading,<br />

opulent building with a wonderful view over the surrounding plains. The estate was<br />

abandoned in August 1982 as fighting in the area reached a stage where tea production was no<br />

longer viable; the tea estate later became a Renamo base.<br />

Fig. 7a,b. Base camp at abandoned tea estate manager's house, Cha Madal (left TH, right CS).<br />

Around the Estate Manager's house many exotic tree species were planted, presumably both<br />

for utilitarian purposes and for shade and beautification. These included Artocarpus<br />

heterophylla (Jackfruit), Eucalyptus cf. grandis (probably for fuelwood and construction),<br />

Vernicia montana (Tung oil), Grevillea robusta, Delonix regia, Ceiba pentandra (Kapok),<br />

Encephalartos cycads and Ficus elastica (India Rubber tree).<br />

The area of plantation tea can be clearly seen in the satellite imagery as a vegetation block<br />

south-east of the main forest area (Figure 4a). The estate was planted with over 600 ha of<br />

China hybrid tea (Camellia sinensis cultivar.), of which 520 ha were in production as of June<br />

1961 (Wilson, Smithett & Co. 1962). As it has not been managed for almost 30 years, the tea<br />

bushes have grown up to 15 m forming an almost solid-canopy forest. Apparently, it may still<br />

be commercially viable if pruned, and could be linked to neighbouring tea-producing areas in<br />

Gurué or even in Mulanje in southern Malawi. Recently, a senior Madal representative<br />

suggested that the planned rehabilitation of the estate may take the form of removing the tea<br />

and replanting with other, more viable crops. However, Madal have now (2011 or early 2012)<br />

sold the estate to a company called Mozambique Holdings.<br />

There is a Soviet map of the area, possibly forming part of a national 1:250,000 series<br />

produced in the late 1970s or early 1980s. The section of the sheet covering Mabu is shown in<br />

Figure 8. It gives a bit more detail than is available on the national Dinegeca 1:250,000 scale<br />

map series, and seems to have been derived separately, possibly from more recent aerial<br />

photos.<br />

On the summit of Mt Mabu we noted the destroyed remains of a trigonometrical point<br />

(presumably from which the spot height of 1710 m was determined), and this was

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 18<br />

subsequently borne out by David Scott (pers. comm., Feb. 2009) who reported constructing<br />

such a point with the Mozambique mapping agency Dinegeca in 1995.<br />

Fig. 8. Soviet map of Mt Mabu and Tacuane area, 1:250,000 scale (probably<br />

late 1970s). Mt Mabu indicated with red arrow.

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 19<br />

4. VEGETATION<br />

4.1 Previous Studies<br />

It seems that there have been no previous studies on, or even recognition of, the vegetation of<br />

Mt Mabu or the immediate area. However, as mentioned earlier, the presence of a number of<br />

tea estates on the lower slopes means that the surrounding vegetation must have been known<br />

to agriculturalists, even if it appears not to have been formally documented.<br />

On a continental or regional scale, the Mabu area is shown by White (1983) as forest patches<br />

of the East African coastal mosaic (type 16b) surrounded by Wetter Zambezian miombo<br />

woodland (type 21). White is wrong in his assertion that these forests are linked to those on<br />

the East African coast as they are clearly montane and medium altitude forests, very similar to<br />

those found on mountains in southern Malawi and Eastern Zimbabwe. The more detailed<br />

study by Wild & Barbosa (1968), on which White's study for this area was based, maps the<br />

Mabu area as Moist Evergreen Forest at low and medium altitudes (Type 1) surrounded by<br />

Brachystegia spiciformis (high rainfall) woodland (Type 21).<br />

The more detailed (and earlier) map of Zambézia Province by Barbosa (1952) shows the<br />

Mabu massif as Unit 1 "Floresta higrófila tropical altimontana, de chuvas e nevoeiros" (moist<br />

high-altitude rain and cloud forest), the same as Mt Namuli, surrounded by Unit 2 "Floresta<br />

sub-higrófila, das altitudes medias, de Brachystegia spiciformis com elementos da floresta<br />

higrófila" (medium-altitude sub-moist forest [woodland] with Brachystegia spiciformis and<br />

moist forest patches). They describe the moist status due to incoming rain and clouds, with a<br />

transition to xerophytic cold-adapted vegetation higher up. A few forest species are listed.<br />

A subsequent, more detailed study by Pedro & Barbosa (1955) looked at vegetation across the<br />

whole country from an agro-ecological viewpoint. The accompanying map shows Mabu<br />

("Alto Lugela") as unit 79 (Zonas altimontanas da Zambézia‒Niassa) occurring between<br />

1000‒1800 m. However, they mention that these zones have not been visited by them so they<br />

can not say much, and no species are listed.<br />

4.2 Vegetation Mapping<br />

Vegetation description of Mt Mabu was carried out by us in two ways ‒ determination of the<br />

possible extent of forest using satellite imagery supported by the use of historical<br />

panchromatic aerial photos, and categorisation of vegetation types seen up the altitudinal<br />

gradient to the peak in the south-eastern part of the massif.<br />

Two separate studies were done for area determination. One was carried out in 2006 using<br />

Landsat 7 ETM+ image (reference S-37-15-2000, 30 m resolution) from the year 2000 viewed<br />

through very near infra-red (VNIR) filters (Bayliss in Spottiswoode et al. 2008). This was not<br />

a supervised classification. The second area determination was done by Julian Bayliss in 2011<br />

using a supervised classification based on locations noted in the field during October 2008<br />

(see below).<br />

Results from the first, Spottiswoode et al. study, although not rigorous, suggested an area of<br />

dense vegetation above 1000 m altitude ‒ which was assumed to be moist forest, but this had<br />

not been confirmed at that stage ‒ of between 5000 and 7000 ha, excluding the fairly obvious<br />

extent of old tea plantation (about 2000 ha, seen through the presence of straight margins,<br />

Figure 4a).

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 20<br />

The second determination of forest extent (J. Bayliss) ‒ the one which we are using here ‒<br />

was done by making a draft vegetation map based on an unsupervised classification using<br />

Erdas Imagine (maximum likelihood algorithm applied to a 6-band stack image) of a Landsat<br />

ETM+ image with 30 m resolution from July 2005 (path 166, row 071). Twelve classes in 9<br />

broad habitat types were recognised, including an 'unclassified' class.<br />

Following fieldwork a final vegetation map was developed using a supervised classification<br />

of the same Landsat image with radiometric and geometric correction, in which four broad<br />

habitat types were separated out ‒ moist forest, woodland, agriculture, rock and bare ground<br />

(Figure 9). Based on this latter interpretation, it was calculated that 6937.4 ha of moist forest<br />

were present on Mt Mabu, most of it above 1000 m; a substantial buffer of woodland is also<br />

shown. Although the figure for forest extent may be an overestimate as the difference between<br />

moist forest and dense woodland is not clear-cut and shadow effects may be significant, it is<br />

thought to be the best estimate possible at this stage without more detailed interpretation and<br />

field survey. Using these figures, forest covers 66% of the total area above 1000 m (see Table<br />

2).<br />

This forested area was divided into altitudinal classes (see Table 4). Out of a total<br />

(planimetric) forest area of 6937.4 ha, 4563.6 ha lies between 1000 and 1400 m, which we<br />

consider to be primarily mid-altitude moist forest, and an additional 919.5 ha lies above 1400<br />

m, which we consider to be high altitude or Afromontane moist forest. In addition, there is a<br />

significant amount of forest below 1000 m, but much of this is riverine or gully forest and<br />

perhaps some is overgrown plantation. The main forest block is that area above 1000 m<br />

altitude, which is 5483 ha.<br />

Table 4. Extent of forest area by altitudinal class for the Mt Mabu massif<br />

(derived from J. Bayliss supervised classification, 2011).<br />

Altitude (m)<br />

measured planimetric<br />

extent (ha)<br />

% estimated extent using<br />

slope correction factors (ha)<br />

below 1000 1454.3 21.0 1600<br />

1000‒1200 1719.9 24.8<br />

1200‒1400 2843.7 41.0<br />

5270<br />

1400+ 919.5 13.2 1010<br />

Total 6937.4 100.0 7880<br />

What should be also taken into account is that these forests are mostly on steep slopes, hence<br />

the actual area covered is significantly larger than the planimetric figures given above. Using<br />

an approximation of a 30 o slope between 1000‒1400 m (not an unreasonable assumption<br />

given the steep slopes there) and an estimated 15 o slope below 1000 m and above 1400 m,<br />

coupled with tangent tables, a rough rounded estimate of forest area in these various<br />

altitudinal bands is shown in the right-hand column of Table 4. The forest extent in the<br />

1000‒1400 m band is 5270 ha, higher than the cumulative planimetric figure of 4564 ha.<br />

Coupled with the forest extent above and below on less steep slopes, this gives a total forest<br />

cover on the mountain (excluding the tea plantations) of around 7880 ha.<br />

In totally separate exercises, the National Land Cover map of Mozambique gives the total<br />

extent (planimetric) of forest cover in the Mabu area as around 5500 ha (J. Francisco, pers.<br />

comm. 2010), while Susana Baena (RBG <strong>Kew</strong> GIS Unit) did an initial partially supervised<br />

classification using 26 ground control points derived from a reconnaissance in June 2008 that<br />

arrived at a more conservative figure of 5998 ha (see Figure 10).

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 21<br />

All these studies show that the area of moist forest is very extensive for the region (between<br />

5500 and 7900 ha) with the great majority of it being found between 1000 and 1400 m. Such<br />

mid-altitude forest is increasingly rare in the southern African region as these areas have often<br />

been cleared in the past 100 years for timber and agriculture. We believe that it represents<br />

perhaps the largest extent of moist forest at such altitudes in southern Africa; in addition these<br />

forests are in excellent condition and little disturbed.<br />

Fig. 9. Supervised classification of Mt Mabu forest vegetation, 2011 (J. Bayliss). Red dots<br />

indicate routes travelled on 2008 expedition.<br />

Fig. 10. Partially-supervised classification of Mt Mabu forest vegetation, early 2008<br />

(S. Baena, RBG <strong>Kew</strong>). Red dots indicate path used in 2006.

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 22<br />

4.3 Vegetation Types<br />

As the expedition only studied vegetation of the lower slopes in the south-eastern corner<br />

above the abandoned tea estate, and was not able to visit the majority of the forested area of<br />

Mt Mabu, any account of the vegetation must be limited in scope. The account below covers<br />

primarily the south-eastern side of the mountain that was extensively visited. Vegetation<br />

types and patterns on the drier western and northern slopes appear to be somewhat different<br />

from those described here (see Section 4.3.5).<br />

Above 600 m altitude vegetation on the Mabu massif can be classified into three main groups<br />

‒ woodland, forest, and scrub/sedge patches on bare rock. Below this altitude abandoned<br />

plantations and secondary vegetation are found, along with patches of lowland riparian forest.<br />

Above 800 m the forest group can be further subdivided into tall riparian forest, tall medium<br />

altitude forest and shorter high altitude ("montane") forest (sub-montane in the classification<br />

of Müller 1999), but within which there was significant variation.<br />

The great majority of the area studied was under forest, the main vegetation type of interest.<br />

In our study less emphasis was placed on woodland and the vegetation of rocky outcrops<br />

around the summit. Boundaries between the different vegetation types were sometimes<br />

surprisingly clear-cut, e.g. between montane forest and low scrub on the summit, and in<br />

places between woodland and medium altitude forest. These 'hard' boundaries may in part be<br />

due to fire.<br />

The main vegetation types are characterised and described below in terms of their structure<br />

(height, cover, etc.), species composition and ecology. This was done both through general<br />

observation and through the recording of 48 vegetation survey plots, each of around 0.25 ha<br />

extent (forest) to 0.5 ha (more open habitats), placed subjectively in what were considered to<br />

be representative sites. A GPS point was recorded for each. Additional clarification was<br />

obtained from viewing old aerial photographs (see Section 2.3) and the use of 0.04 ha forest<br />

mensuration plots (see Section 4.4). The descriptions follow an altitudinal sequence.<br />

Additional details on vegetation are given in Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett (2009).<br />

4.3.1 Plantations (400‒600 m)<br />

Around the ruined tea estate manager's house (16°18'20.5"S, 36°25'28.8"E, 550 m) there are a<br />

number of overgrown plantations of tea (Camellia sinensis) and Eucalyptus cf. grandis. Tea<br />

bushes, originally kept to around 1.5 m in height, have now grown up to 12–14 m high, many<br />

2–3 stemmed with stems 10–15 cm in diameter. These are overtopped by Albizia<br />

adianthifolia, locally forming a closed canopy. Other native trees found here include<br />

Macaranga capensis.<br />

Much of the planted and secondary growth around this area contains exotics (Grevillea<br />

robusta, Delonix regia, Eucalyptus cf. grandis and Vernicia montana) mixed with pioneer<br />

forest trees such as Macaranga capensis. Other exotics planted near the estate manager's<br />

house include Ceiba pentandra, Artocarpus heterophyllus (jackfruit) and Ficus lutea.<br />

4.3.2 Woodland (600‒1000 m)<br />

This type was not examined in detail, but on the lower sections of the main path up to Mt<br />

Mabu the woodland is clearly dominated by Pterocarpus angolensis. Other common trees<br />

include Pteleopsis myrtifolia and Vitex doniana, while Pericopsis angolensis and<br />

Stereospermum kunthianum were noted occasionally. The woodland is underlain by a carpet<br />

of Aframomum albiflorum; clumps of Oxytenanthera abyssinica bamboo often grow at the<br />

ecotone between woodland and dry forest or near dry streams. With increasing altitude,<br />

Syzygium cordatum becomes more common until it is locally dominant above 800 m (Figure<br />

11), forming pure stands sometimes closed enough to be called forest. Aframomum remains

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 23<br />

common under Syzygium and the number of low-level epiphytes (ferns and orchids, also<br />

Rhipsalis) at 800–950 m suggests a high level of humidity for much of the year.<br />

At 900 m the transitional woodland‒forest on the ridge is drier, being dominated by Syzygium<br />

cordatum and Xylopia aethiopica. Other species noted were emergent Newtonia buchananii,<br />

Albizia adianthifolia and Macaranga capensis, with an understorey of Craterispermum<br />

schweinfurthii, Cussonia arborea, Englerophytum magalismontanum, Erythroxylum<br />

emarginatum, Oxyanthus speciosus, Phoenix reclinata, Synsepalum cerasiferum and<br />

Tabernaemontana ventricosa. Lianas were mainly Dalbergia lactea, Landolphia kirkii and<br />

Urera trinervis.<br />

Fig. 11. Moist woodland (Syzygium<br />

cordatum) at forest margin (JT).<br />

Fig. 12 a,b. Burnt woodland in agricultural zone on lower SE slopes of Mt Mabu (left, TH); woodland<br />

at forest margin showing boundary (right, JT).<br />

4.3.3 Moist Forest (400‒1650 m)<br />

The following categories of forest can be recognized: lowland riparian forest (400–900 m),<br />

mid-altitude moist forest (980 to 1350–1400 m) and Afromontane moist forest (from 1350–<br />

1400 m to 1650 m). Only the latter two were extensively studied by us.<br />

a) Lowland riparian forest (400‒1000 m)<br />

This forest type occurs over a significant altitudinal range and is fairly narrow in extent, so<br />

varies greatly in its composition and structure.<br />

Lower down, in patches of lowland riparian forest at 400–500 m near the tea estate<br />

managers's house (16°18'26"S, 36°25'39"E), large (40‒50 m high) trees of Albizia<br />

adianthifolia (dominant), Erythrophleum suaveolens, Khaya anthotheca, Macaranga

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 24<br />

capensis, Newtonia buchananii, Parkia filicoidea, Pteleopsis myrtifolia and Synsepalum<br />

cerasiferum were noted in the canopy. Edge or pioneer species included Bridelia micrantha,<br />

Harungana madagascariensis, Trema orientalis and Vitex doniana, while understorey species<br />

included Dracaena mannii, Celtis gomphophylla, Clausena anisata, Ensete ventricosum and<br />

various lianes.<br />

Lowland riparian forest at 800–900 m near the path to the main forest camp was characterised<br />

by 45 m high emergent trees of Newtonia buchananii (Khaya anthotheca was rarely seen),<br />

with other canopy trees being Albizia adianthifolia, Anthocleista grandiflora, Erythrophleum<br />

suaveolens, Macaranga capensis, Parinari excelsa, Synsepalum cerasiferum and Xylopia<br />

aethiopica, with Pteleopsis myrtifolia, Vitex doniana and, locally, Shirakiopsis (Sapium)<br />

elliptica at the edges. The commonest understorey species were Craterispermum<br />

schweinfurthii and Erythroxylum emarginatum; others include Dracaena mannii, Oxyanthus<br />

speciosus, Englerophytum magalismontanum, Tabernaemontana ventricosa, small trees and<br />

saplings of Cryptocarya liebertiana, Cussonia spicata and Polyscias fulva (from 850 m).<br />

Oreobambos buchwaldii bamboo was fairly common, and locally the palm Phoenix reclinata.<br />

The tree fern Cyathea dregei occurs along the main streams, the large fern Marattia fraxinea<br />

is frequent, and the shrub Carvalhoa campanulata grows in light gaps. The commonest<br />

canopy liana by far is Millettia lasiantha, found with various Apocynaceae (Dictyophleba,<br />

Landolphia kirkii, Saba comorensis), Combretum paniculatum, Dalbergia lactea and Urera<br />

trinervis.<br />

b) Mid-altitude moist forest (980‒1400 m) (Figures 13, 14)<br />

This is found between the altitudes of 980–1000 m and 1350–1400 m, after which a sudden<br />

change in the dominant canopy species occurs.<br />

From the forest plots (see Section 4.4) and general observation, the main forest canopy trees<br />

in terms of basal area in the lower parts of medium-altitude forest were Strombosia scheffleri,<br />

Newtonia buchananii, Chrysophyllum gorongosanum and Maranthes goetzeniana. In<br />

addition, Cryptocarya liebertiana, Ficus sansibarica and Trichila dregeana were also seen.<br />

Occasional large trees of Cassia angolensis were noted elsewhere. Large strangling figs at<br />

1000–1350 m belong to two species, Ficus sansibarica and Ficus thonningii, replaced at<br />

higher elevations by Ficus scassellatii. Away from the stream gullies the forest canopy is<br />

usually closed, except for small gaps caused by tree-falls.<br />

The main sub-canopy trees (often with more stems but alower basal area) were Drypetes<br />

gerrardii, Drypetes natalensis, Funtumia africana, Garcinia kingaensis, Rawsonia lucida,<br />

Tabernaemontana ventricosa and a number of Rubiaceae including Heinsenia diervilleoides,<br />

Aidia micrantha, Tricalysia acocantheroides (all the way to the top) and Tricalysia pallens.<br />

Other sub-canopy trees and shrubs seen included Allophylus chaunostachys, Blighia<br />

unijugata, Cola greenwayi, Diospyros abyssinica (starts appearing just above 1100 m),<br />

Myrianthus holstii, Oxyanthus speciosus, Vepris nobilis and Zanthoxylum gilletii.<br />

Haplocoelum foliolosum is common from 1150–1300 m and the first big Tabernaemontana<br />

stapfiana appear on the ridge at 1200–1250 m. Canopy lianas are dominated by Millettia<br />

lasiantha, with Acacia pentagona, Agelaea heterophylla, Combretum paniculatum,<br />

Dictyophleba lucida, Landolphia kirkii, Oncinotis tenuiloba and Urera trinervis also<br />

common.<br />

Enormous clumps of Oreobambos buchwaldii bamboo to 18–20 m tall are frequent all the<br />

way up to 1400 m, particularly on dry slopes and in gullies.<br />

At around 1000 m near the main forest camp (16°17'10"S, 36°24'01"E), tall trees reach an<br />

impressive height of 40–45 m (see front cover), with Strombosia scheffleri being the

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 25<br />

commonest (largest between 45–50 m tall, 90 cm DBH). Apart from Strombosia, common<br />

canopy large trees here were Newtonia buchananii (largest seen 50 m tall, 140 cm DBH),<br />

Chrysophyllum gorungosanum (over 45 m) and Maranthes goetzeniana (40 m, 35 cm DBH).<br />

At about 1100 m altitude, beyond a large rocky stream (16°17'05"S, 36°23'44"E) on a gentle<br />

slope, the forest is very impressive with the tallest trees (at least 40 m) including many<br />

Strombosia. Several Chrysophyllum gorungosanum, Maranthes goetzeniana and Newtonia<br />

buchananii were noted, with one or two tall Cryptocarya liebertiana, Trichilia dregeana and<br />

strangling figs (Ficus sansibarica). In the subcanopy Drypetes gerrardii, Garcinia kingaensis<br />

and Myrianthus holstii were seen. Smaller trees include Drypetes natalensis (also conspicuous<br />

along the stream, with arching branches), Pavetta gurueënsis, Rawsonia lucida, Rinorea<br />

ferruginea, Vepris sp. nov. and Synsepalum muelleri.<br />

Steep, wide gullies with permanent streams contain more light-demanding tree species such<br />

as Albizia adianthifolia, Macaranga capensis, Newtonia and Polyscias fulva (the latter<br />

becoming bigger and more frequent with increasing altitude). Also found here were<br />

Anthocleista grandiflora, Funtumia africana and medium-sized Bridelia micrantha,<br />

Englerophytum magalismontanum, Xylopia aethopica and small Bersama abyssinica. Tree<br />

ferns (Cyathea dregei) occur along streams to at least 1400 m while Dracaena fragrans is<br />

common in humid hollows and on some slopes.<br />

Fig. 13 a,b. Medium altitude moist forest, near Mt Mabu campsite (JB).<br />

Fig. 14. Medium altitude moist<br />

forest canopy, Mt Mabu (JT).<br />

c) Afromontane forest (1350‒1650 m) (Figures 15, 16)<br />

This forest type with its lower canopy height and much moister aspect is found up to 1650 m.<br />

The change from medium-altitude to high altitude forest is fairly abrupt at about 1350‒1400

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 26<br />

m, at least on the south-eastern slopes, and is seen in the dropping out of Newtonia<br />

buchananii, the replacement of Albizia adianthifolia by A. gummifera, and in Olea capensis<br />

becoming a conspicuous tall tree.<br />

Canopy trees in the lower parts of Afromontane forest include Strombosia scheffleri,<br />

Chrysophyllum gorungosanum, Maranthes goetzeniana and Newtonia buchananii, with Cola<br />

greenwayi, Garcinia kingaensis, Heinsenia diervilleoides, Myrianthus holstii,<br />

Tabernaemontana stapfiana and Vepris nobilis in the sub-canopy. Small Cassipourea<br />

malosana and the understorey tree Lasiodiscus usambarensis appear around 1300 m, while<br />

Maytenus acuminata and Eugenia capensis subsp. nyassensis are common between 1300–<br />

1400 m. Higher up Podocarpus latifolius becomes increasingly common. Anthocleista<br />

grandiflora and Polyscias fulva are found in openings or gaps.<br />

One site on a ridge in the transition zone (16°17'31"S, 36°23'34"E, 1400 m), had several large<br />

Newtonia, Olea capensis, Parinari excelsa and Polyscias fulva (30–35 m tall), with Aphloia<br />

theiformis in the gaps. Other trees present included Chrysophyllum gorungosanum,<br />

Maranthes goetzeniana, Strombosia scheffleri and Zanthoxylum gilletii in the canopy, and<br />

Cola greenwayi, Craibia brevicaudata, Garcinia kingaensis, Myrianthus holstii,<br />

Tabernaemontana stapfiana and Vepris nobilis in the subcanopy. Common small trees and<br />

shrubs were Alchornea hirtella, Heinsenia diervilleoides, Carissa bispinosa, Chassalia<br />

parvifolia, Clausena anisata, Diospyros abyssinica, Dovyalis macrocalyx, Dracaena<br />

laxissima, Drypetes natalensis, Erythrococca polyandra, Eugenia capensis subsp. nyassensis,<br />

Lasianthus kilimandscharicus, Maytenus acuminata, Mostuea brunonis, Pauridiantha<br />

paucinervis, Pavetta gurueënsis, Peddiea fischeri, Psychotria zombamontana, Rinorea<br />

angustifolia, Rytigynia uhligii, Synsepalum muelleri, Tricalysia acocantheroides, Vepris sp.<br />

nov., Vepris nobilis and Memecylon sp. (FD-L 2538, 2–4 m tall).<br />

At the upper end of the forest at 1600 m, the taller trees (to 25 m high) are Olea capensis and<br />

Rapanea melanophloeos, with lower trees of Aphloia theiformis, Bersama abyssinica,<br />

Cassine aethiopica, Cassipourea malosana, Cryptocarya liebertiana, Faurea racemosa,<br />

Macaranga capensis, Nuxia congesta, Ochna holstii, Pittosporum viridiflorum, Podocarpus<br />

latifolius, Polyscias fulva, Prunus africana and Syzygium guineense subsp. afromontanum.<br />

Conspicuous lianas at the forest edge include Rutidea orientalis and Schefflera goetzenii,<br />

which are already common around 1400 m, and Canthium gueinzii.<br />

Lower down at 1550‒1600 m the following small understorey trees and shrubs were noted:<br />

Carissa bispinosa, Chassalia parvifolia, Diospyros abyssinica, Diospyros whyteana (at<br />

edges), Dovyalis macrocalyx, Dracaena laxissima, Erythroxylum emarginatum, Eugenia<br />

capensis, Lasianthus kilimandscharicus, Maytenus acuminata, Mostuea brunonis, Pavetta<br />

gurueënsis, Rinorea angustifolia, Rytigynia uhligii, Tricalysia acokantheroides, Memecylon<br />

sp. (FD-L 2538) and Vepris nobilis.<br />

Fig. 15. Montane forest on upper<br />

slopes of Mt Mabu (TT).

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 27<br />

Fig. 16. View over montane forest on Mt Mabu (JB).<br />

4.3.4 Montane Shrubland (1600‒1700 m) (Figures 18, 19, 20)<br />

At 1600–1700 m just below the peak there is a limited area of montane shrubland where large<br />

boulders and rocky slopes are covered by scattered tufts of grass and sedge. Above this the<br />

summit is exposed and vegetation comprises mostly sedges and shrubby herbs. Such<br />

vegetation appears to be very typical of exposed granitic peaks across the region. Less time<br />

was spent exploring this habitat, which covers just a few hectares on the rounded peaks.<br />

Much of the area is bare rock with patches of small trees and shrubs in sheltered or more<br />

moisture-rich sites. In these patches Rapanea melanophloeos is the most frequent small tree,<br />

next to a few stunted Syzygium cordatum, Aphloia theiformis, Maytenus acuminata,<br />

Aeollanthus buchnerianus, Tetradenia riparia and Dissotis sp. Scattered Aloe arborescens<br />

were also seen.<br />

In somewhat more exposed sites, the dominant low shrub, 0.5–2.5 m high is Aeschynomene<br />

nodulosa, along with Kotschya recurvifolia. Common prostrate or semi-prostrate herbs<br />

include Ipomoea involucrata, Corrigola drymerioides, Indigofera sp. and Lobelia trullifolia.<br />

The dominant feature, however, is large clumps of the sedge Coleochloa setifera (Figure 17),<br />

with smaller clumps of the grasses (?)Danthoniopsis sp. and Helictotrichon elongatum and<br />

the sedge Cyperus fischerianus. Many of the large clumps had an abundance of the small<br />

pink-flowered orchid, Polystachya songaniensis (Figure 22).

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 28<br />

Fig. 17. Coleochloa 'grassland'<br />

on rocky slopes near summit of<br />

Mt Mabu (TT).<br />

Fig. 18. Upper forest margin with montane<br />

shrubland and Coleochloa 'grassland' (JT).<br />

Fig. 19. Montane shrubland near summit of Mt<br />

Mabu (JT).<br />

Fig. 20. Montane shrubland near summit of Mt Mabu (JT).

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 29<br />

4.3.5 Vegetation of the Drier Western and Northern Slopes<br />

In the western parts of the massif, which lie in the rain shadow and away from the prevailing<br />

oceanic moisture-bearing air currents, aerial photographs and study of Google Earth imagery<br />

suggest that the lower limit of moist forest is around 1200‒1250 m, although extending lower<br />

to 1050 m on sheltered slopes and along drainage lines and gullies. On the northern boundary<br />

the lower limit is around 1400 m. Below the forest on this drier side is what appears to be<br />

woodland and bushland. However, as these areas were not visited it is not possible to confirm<br />

this. This compares to a lower forest limit of 950 m in gullies and valleys on the southern and<br />

eastern slopes.<br />

There appears to be a marked break on the western side of Mabu between higher altitude<br />

forest (smooth texture, low canopy height) and medium altitude forest (rough texture, varying<br />

canopy height and colour) at around 1350‒1400 m. This disjunction is not so apparent on the<br />

moister eastern slopes.<br />

4.4 Forest Plots<br />

In order to help characterise forest composition and density, nine 20 × 20 m (0.04 ha)<br />

enumeration plots were recorded. These were all sited within 1 km of the main campsite, 8 in<br />

medium-altitude forest and one in adjacent woodland near a small stream. All trees were<br />

identified to species, and diameter breast height (dbh) for trees above 5 cm dbh recorded<br />

along with an estimated height. Summarised results are shown in Table 5.<br />

In the eight forest plots, the main large canopy trees in terms of basal area were (in declining<br />

order of importance): Newtonia buchananii (primarily in Plot 5), Strombosia scheffleri,<br />

Chrysophyllum gorongosanum and Maranthes goetzeniana. The main sub-canopy trees (often<br />

with more stems but lower basal area) were Drypetes gerrardii, Funtumia africana, Rawsonia<br />

lucida, Drypetes natalensis and a number of Rubiaceae (many being unidentified species but<br />

also Heinsenia diervilleoides and Aidia micrantha). Plot 1 was situated in the main campsite.<br />

The total number of stems over 5 cm dbh recorded in the forest plots was 279, giving a mean<br />

stem density of around 872 stems/ha. Figures for each plot ranged from 50 (= 1250 stems/ha)<br />

down to 20 (= 500 stems/ha).<br />

Mean basal area of all trees above 5 cm dbh for the eight forest plots was 29.94 (= 93.56<br />

m 2 /ha), ranging from 1.97 m 2 (= 49.32 m 2 /ha) to 5.72 m 2 (= 143.0 m 2 /ha). Of this figure, the<br />

four main canopy trees comprised over 76%, while the main sub-canopy trees (including<br />

unidentified Rubiaceae) contributed a further 16%, giving a combined total of over 92%.<br />

In the woodland plot (Plot 9) the major trees were Syzygium cordatum and Parinari excelsa,<br />

both in terms of number of stems in the plot (11 and 8 respectively) and basal area (equivalent<br />

to 36.55 and 8.61 m 2 /ha, respectively). Total basal area was 2.0782 (= 51.96 m 2 /ha). There<br />

were only 4 tree species in the woodland plot in comparison to the forest plots, which had<br />

from 9 to 17 species (mean 14.5).<br />

4.5 Observations on Tree Fruiting<br />

A striking feature of the forest on Mabu during the expedition was the near-absence of figs on<br />

large stranglers, in contrast to the situation for example in Malawi when October is normally a<br />

productive month and large hornbills are breeding (Dowsett-Lemaire & Dowsett 2006). Of<br />

the more than 30 strangler figs examined, only one Ficus bubu was in fruit, one F. scassellatii<br />

was in unripe fruit and another had ripe figs. Not a single F. thonningii nor F. sansibarica was<br />

fruiting. The ripe figs of F. scassellatii were taken by Silvery-cheeked Hornbills and Green

Biodiversity of Mt Mabu, Mozambique, page 30<br />

Barbets, but observations were of short duration.<br />

Of other large trees, Olea capensis were generally flowering except for a few trees at the<br />

forest edge at 1600 m that were out of phase and fruiting (with attendant Rameron Pigeons).<br />

Cryptocarya were also in flower, and Polyscias were near the end of the fruiting season<br />

(Rameron Pigeons were seen eating them). Aphloia were in young, fully formed fruit (already<br />

consumed by Green Barbet and Stripe-cheeked Greenbul). Lower down at 900 m, several<br />

Xylopia aethiopica were in ripe fruit, the arils being eaten occasionally by Green Barbet,<br />

White-eared Barbet, Golden-rumped Tinkerbird and Little Greenbul. One pair of Green<br />

Barbets was breeding there in a territory including many fruiting Xylopia, and the local<br />

Syzygium cordatum (some flowering) will provide an abundance of fruits in the middle of the<br />

rainy season. At 1600 m, a tall Syzygium guineense had just finished flowering. The fruiting<br />

of Pittosporum (common at 1600 m) was finished, with some old capsules still visible on the<br />