Biodiversity (1 - SRK Consulting

Biodiversity (1 - SRK Consulting

Biodiversity (1 - SRK Consulting

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

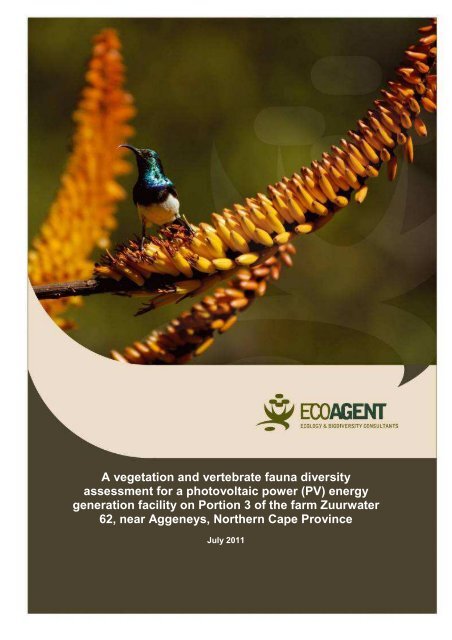

A vegetation and vertebrate fauna diversity<br />

assessment for a photovoltaic power (PV) energy<br />

generation facility on Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater<br />

62, near Aggeneys, Northern Cape Province<br />

July 2011

July 2011<br />

A vegetation and vertebrate fauna diversity<br />

assessment for a photovoltaic power (PV) energy<br />

generation facility on Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater<br />

62, near Aggeneys, Northern Cape Province<br />

Commissioned by:<br />

<strong>SRK</strong> <strong>Consulting</strong> Engineers and Scientists<br />

Conducted by<br />

EcoAgent CC<br />

PO Box 23355<br />

Monument Park<br />

0181<br />

Tel 012 4602525<br />

Fax 012 460 2525<br />

Cell 082 5767046<br />

Contributors:<br />

G.J. Bredenkamp D.Sc., Pr.Sci.Nat., Botanist<br />

I.L. Rautenbach Ph.D., Pr.Sci.Nat., Mammalogist<br />

A. Kemp Ph.D., Pr.Sci.Nat., Ornithologist<br />

J.C.P. van Wyk M.Sc., Pr.Sci.Nat., Herpetologist<br />

July 2011<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 2

Some of the rare or beautiful succulent plants found on the Farm Zuurberg 62<br />

near Aggeneys, Northern Cape Province<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE ................................................................... 12<br />

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ 13<br />

1. PROJECT BACKGROUND ................................................................................ 16<br />

2. ASSIGNMENT ................................................................................................. 19<br />

2.1. Initial preparations: .................................................................................... 19<br />

2.2. Vegetation and habitat survey: .................................................................. 19<br />

2.3. Plant community delimitation and description ............................................ 19<br />

2.4. Faunal assessment ................................................................................... 20<br />

2.5. General ..................................................................................................... 20<br />

3. RATIONALE .................................................................................................... 21<br />

4. SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY.................................................. 23<br />

5. STUDY AREA ..................................................................................................... 24<br />

5.1 Regional setting ............................................................................................. 24<br />

5.2 Physical Environment .................................................................................... 26<br />

5.3 Vegetation Types ........................................................................................... 27<br />

5.4 The Study Site for the Proposed Development .............................................. 28<br />

6. METHODS .......................................................................................................... 31<br />

6.1. Flora.......................................................................................................... 31<br />

6.1.1 Vegetation and flora ................................................................................ 31<br />

6.1.2 Plant Conservation Priority ................................................................. 32<br />

6.1.3 Sensitivity ........................................................................................... 33<br />

6.2. Mammals .................................................................................................. 33<br />

6.2.1. Field Survey ....................................................................................... 34<br />

6.2.2. Desktop Survey .................................................................................. 34<br />

6.2.3. Specific Requirements ....................................................................... 35<br />

6.3. Birds.......................................................................................................... 35<br />

6.3.1 Bird Habitats ...................................................................................... 36<br />

6.3.2 Bird Species ....................................................................................... 38<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 4

6.3.3 Field Survey ....................................................................................... 38<br />

6.3.4 Desktop Survey .................................................................................. 39<br />

6.4. Herpetofauna ............................................................................................ 41<br />

6.4.1. Field Surveys ..................................................................................... 41<br />

6.4.2. Desktop Surveys ............................................................................... 41<br />

6.4.3. Specific Requirements ....................................................................... 42<br />

7. RESULTS: VEGETATION AND FLORA ............................................................ 44<br />

7.1 Classification of the vegetation ...................................................................... 44<br />

7.2 Description of the plant communities ............................................................. 45<br />

1 Bushmanland Sandy Grassland .................................................................... 45<br />

2 Bushmanland Arid Grassland ........................................................................ 48<br />

2.1. Grassland on sandy hummocky plains ...................................................... 50<br />

2.2. Grassland on flat sandy plains................................................................... 51<br />

3. Gravelly calcrete plains (=Aggeneys Gravel Vygieveld) ................................ 52<br />

4. Bushmanland Inselberg Shrubveld ............................................................... 53<br />

4.1 Shrubveld on mountains, hills, slopes and crests ....................................... 54<br />

4.2 South facing slopes .................................................................................... 55<br />

4.2.1 South-facing scree slopes ....................................................................... 55<br />

4.2.2 Steep south-facing slopes ....................................................................... 57<br />

4.3 Rocky north-facing foot slopes ................................................................... 58<br />

5. Azonal vegetation ......................................................................................... 60<br />

5.1 Pans ........................................................................................................... 60<br />

5.2 Washes ...................................................................................................... 63<br />

7.3 <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Areas .......................................................................................... 64<br />

7.4 Fine Scale <strong>Biodiversity</strong> ................................................................................... 67<br />

7.5 Zuurberg Important <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Areas ........................................................... 67<br />

7.6 Sensitive Vegetation ...................................................................................... 69<br />

7.7 Species of Conservation Concern .................................................................. 70<br />

7.7.1 Protected species .................................................................................... 71<br />

7.7.2 Threatened species ................................................................................. 71<br />

7.8 Land Use in the Zuurwater Area .................................................................... 72<br />

7.9. Discussion .................................................................................................... 74<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 5

7.10 References .................................................................................................. 75<br />

8. RESULTS: MAMMALS ....................................................................................... 78<br />

8.1 Mammal Habitat Assessment ................................................................... 78<br />

8.2 Observed and Expected Mammal Species Richness ................................ 82<br />

8.3 Red Listed Mammals ................................................................................ 85<br />

8.4 Discussion ..................................................................................................... 86<br />

8.5 Conclusion ..................................................................................................... 87<br />

8.6 References .................................................................................................... 87<br />

9. RESULTS: AVIFAUNA ....................................................................................... 90<br />

9.1 General .......................................................................................................... 90<br />

9.2 On-site Bird Habitat Assessment ............................................................... 90<br />

9.3. Expected and Observed Bird Species Diversity ...................................... 100<br />

9.4. Threatened and Red-Listed Bird Species ................................................ 106<br />

9.5. General Conclusions................................................................................... 108<br />

9.6 Limitations, Assumptions and Gaps in Knowledge ...................................... 109<br />

9.7 References .................................................................................................. 109<br />

10. RESULTS: HERPETOFAUNA ........................................................................ 112<br />

10.1. Herpetofauna Habitat Assessment ............................................................ 112<br />

10.2. Observed and Expected Herpetofauna Species Richness ................... 119<br />

10.3. Red Data Listed Reptiles .......................................................................... 120<br />

10.4. Red Data Listed Amphibians ..................................................................... 121<br />

10.5 Discussion ................................................................................................. 126<br />

10.6 Conclusions ............................................................................................... 128<br />

10.7. References ............................................................................................... 128<br />

11. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR BIODIVERSITY ............... 130<br />

11.1 The ecological importance of the study site ............................................ 130<br />

11.2 General impacts associated with PV arrays ............................................ 130<br />

12 RECOMMENDED MITIGATION MEASURES .................................................. 139<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 6

12.1 Specific mitigation measures ..................................................................... 139<br />

12.2 Generic Mitigation measures ..................................................................... 142<br />

13. ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN .................................................... 143<br />

Fauna and Flora ............................................................................................. 144<br />

Decommissioning phase ................................................................................ 145<br />

Flora ............................................................................................................... 146<br />

Fauna ............................................................................................................. 146<br />

APPENDICES ....................................................................................................... 147<br />

APPENDIX 1: EIA METHODS ........................................................................... 147<br />

APPENDIX 2: CURRICULII VITAE .................................................................... 152<br />

Abridged Curriculum Vitae: George Johannes Bredenkamp .............................. 152<br />

Abridged Curriculum Vitae: Ignatius Lourens Rautenbach ................................. 158<br />

Abridged Curriculum Vitae: Alan Charles Kemp ................................................. 160<br />

Abridged Curriculum Vitae: Jacobus Casparus Petrus van Wyk ........................ 164<br />

List of Figures<br />

Figure 1. Map of solar radiation, showing the high levels of radiation expected in<br />

western South Africa (www.slc-group.net) ............................................................... 16<br />

Figure 2. The locality of the SATO/SHE property, Portion 3 of the Farm Zuurwater<br />

63, in relation to Aggeneys, the N14 National Road and the Koa River drainage<br />

system..................................................................................................................... 24<br />

Figure 3. Satellite image showing the location of Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater 63<br />

(purple line), in relation to the N14 National Road and the currently dominant<br />

drainage line of the Koa River wash. Aggeneys mines and villages are situated in<br />

and below the hills just above the N14 sign. ............................................................ 25<br />

Figure 4. Satellite image of Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater 62 (purple lines), in<br />

relation to the general area around Aggeneys and the route of the N14 National<br />

Road. ...................................................................................................................... 25<br />

Figure 5. Satellite image of Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater 62 (purple lines), showing<br />

the principal features of and names for the topography, habitats and relevant<br />

neighbouring features. ............................................................................................. 26<br />

Figure 6. Close-up satellite image of the east-central section of Portion 3 of the farm<br />

Zuurwater 62 (cf. Figures 2-4), showing the principal habitat and topographical<br />

features influencing the identification of this site as ecologically of low sensitivity but<br />

still technologically and socially suitable. The least ecologically sensitive sector of the<br />

development (1, thick dark blue line) is proposed for west of the N14 (yellow line),<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 7

with adjacent slightly more sensitive extensions, including east of the N14 (2, shaded<br />

pale blue), and an even less preferable north-western extension (3, thin dark blue<br />

line).The route of a high-voltage transmission line and pylons (green lines) is also<br />

shown, from the Eskom substation to the east to Springbok in the west. The eastern<br />

boundary of Zuurwater is also shown (purple line). Engineers will present a final<br />

footprint, outline and spacing for how to fit the 5-panel table arrays into minimum<br />

non-sensitive space available and as close as possible to the Eskom substation.<br />

Access to a water pipeline between Zuurwater farmhouse and Aggeneys also has to<br />

be accommodated. .................................................................................................. 29<br />

Figure 7. Impression of how solar panel tables are arranged and spaced, but note<br />

this is only a 2-deep panel array, supported on a single leg/foot line embedded in the<br />

ground and with only a narrow space between tables (from www.slc-group.net). The<br />

Zuurwater design calls for a 5-deep array, supported on a 2-feet line and bolted to a<br />

concrete slab resting on the ground surface, and with an 8 m shade gap between<br />

tables. ..................................................................................................................... 30<br />

Figure 8. View of power connection and distribution cables housed under the solar<br />

panel tables. The design allows small livestock to graze under and around the tables<br />

(sheep, but not goats, cattle or horses on Zuurwater). The upper surfaces of the solar<br />

panels are washed automatically with water at appropriate intervals, and the waste<br />

runs into collection channels for recycling (from www.slc-group.net). ...................... 30<br />

Figure 9. Vegetation map of the study site .............................................................. 45<br />

Figure 10. Typical Bushmanland Sandy Grassland with mobile sand dunes ........... 46<br />

Figure 11. Bushmanland Sandy Grassland on the sands dunes. ............................ 46<br />

Figure 12. Stipagrostis namaquensis typical of dune crests. ................................... 47<br />

Figure 12: Figure 13. Typical Bushmanland Arid Grassland. Note the Inselberg on<br />

the right. .................................................................................................................. 49<br />

Figure 14. Grassland on sandy hummocky plains ................................................... 51<br />

Figure 15. Grassland on flat sandy plains ................................................................ 52<br />

Figure 16. Typical mountains and hills – the habitat of Bushmanland Inselberg<br />

Shrubveld. ............................................................................................................... 53<br />

Figure 17. A scree slope ......................................................................................... 57<br />

Figure 18 Steep south-facing slopes and cliffs ........................................................ 58<br />

Figure 19. Rocky north-facing slopes ...................................................................... 59<br />

Figure 20. Two examples of Pans – above dry during the survey period, below still<br />

with water. ............................................................................................................... 62<br />

Figure 21. Critical <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Areas (CBA’s) in the Namakwa District Municipality.<br />

Note the presence of CBA1 north of Aggeneys, with CBA2 in the vicinity, while an<br />

Ecological Support Area (ESA) forms a corridor south of Aggeneys (from Marsh et al.<br />

2009) ....................................................................................................................... 65<br />

Figure 22. Map indicating biodiversity areas (Image provided by <strong>SRK</strong> <strong>Consulting</strong>) . 67<br />

Figure 23. Map indicating Zuurwater Important <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Areas (SKEP 2005)<br />

(Image provided by <strong>SRK</strong> <strong>Consulting</strong>) ...................................................................... 68<br />

Figure 24. Sensitive vegetation types (Image provided by <strong>SRK</strong> <strong>Consulting</strong>) ............ 69<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 8

Figure 25. The vegetation sensitivity map compiled for the site during this survey. . 70<br />

Figure 26. A map indicating the Black Mountain Land Use Plan (SKEP 2008) with the<br />

Zuurwater area immediately west of the mining area (Image provided by <strong>SRK</strong><br />

<strong>Consulting</strong>) .............................................................................................................. 73<br />

Figure 27. A south-westerly view over the gravelly plain earmarked for the proposed<br />

development. Note the sparse basal cover. ............................................................ 80<br />

Figure 28. The dammed water in the Koa River wash and pan. This water body<br />

appears to be a permanent feature and as such probably support insects which can<br />

be expected to rise during summer sunsets and serve as feeding patches for<br />

hawking bats commuting from roosting sites in the various mountains on the<br />

property. .................................................................................................................. 80<br />

Figure 29. An aardvark burrow in the Kalahari duneveld. ........................................ 81<br />

Figure 30. The Bobbejaansgat Mountain. The many boulder overhangs and deep<br />

crevices are likely to offer suitable daytime roosting sites for bats. .......................... 81<br />

Figure 31. View north down the Koa River drainage where the deepest part passes<br />

under the N14, about where the eastern boundary of Zuurwater meets the road. Note<br />

the good but patchy stands of grasses, few woody plants, and the mountains,<br />

Hoedkop (left) around Aggeneys in the background (right). ..................................... 91<br />

Figure 32. View west from the east boundary of Zuurwater, with Hoedkop on the<br />

centre and Skelemberg on the left horizon, showing the open flats of the Koa wash<br />

with the Springbok powerline on the right side of the proposed northeast end of the<br />

PV arrays. ............................................................................................................... 91<br />

Figure 33. View east from the Zuurwater farmhouse, showing a Karoo Korhaan in the<br />

overgrazed plains on a calcrete substrate with shallow soils and some Rhigozum<br />

trichotomum shrubs, the sort of habitat at the south end of the PV array. ................ 92<br />

Figure 34. View east from a dune crest in the northern dune fields, looking across a<br />

dune street with a lone Acacia karroo to the Springbok power lines coming from the<br />

Eskom substation behind the Aggeneys hills on the left. ......................................... 93<br />

Figure 35. View south west from rocky outcrop at crest of the northern dune field on<br />

Zuurwater, showing the tussocky grass, few trees/bushes and the Koa wash behind,<br />

with the Skelemberg on the left and Hoedkop on the right. ...................................... 93<br />

Figure 36. View north from the southern sandy area with mainly Centropodia grass,<br />

looking north of the eastern half of the Windhoekberg (with the N14 passing at the<br />

extreme left of the picture. ....................................................................................... 94<br />

Figure 37. View west from northeast corner of Zuurwater, showing the pan just inside<br />

the fenceline that forms the downstream end and overflow of water from the mine<br />

dam/vlei just outside the farm. Hoedkop ison the horizon. ....................................... 95<br />

Figure 38. View west down the main Koa River wash where it would flow into the<br />

wide expanese of Pan 1, looking along the fence line that marks the approximate<br />

northern edge of the PV array and also the ecotone between the open plains (left)<br />

and the start (right) of the northern dune fields. Hoedkop is in the background, with<br />

Pan 2 near its base. ................................................................................................ 95<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 9

Figure 39. View west towards Hoedkop, looking across Pan 2 and the water that<br />

accumulated in the ditch dug across its centre from the unexpected 30 mm of rain<br />

that fell the fortnight before. ..................................................................................... 96<br />

Figure 40. Panoramic view along the south side of Windhoekberg W, showing the<br />

steep, shaded southern slope, the collections of rocks and gravels forming a skirt<br />

around its base, and the small drainage lines formed by previous runoff. Note the<br />

lack of mountains to the west towards Springbok and the Namaqualand habitats. .. 97<br />

Figure 41. Panoramic view over the north side of Skelemberg, showing the less<br />

steep, sunny northern slope, with fewer rocks and gravels forming less of a skirt<br />

around its base, but many small drainage lines from previous runoff and denser<br />

bushes around the 'gutter'. Hoedkop is on the left and the Aggeneys mountains on<br />

the centre horizon. .................................................................................................. 97<br />

Figure 42. Patch of green vegetation formed on the gravel skirt below the north slope<br />

of the western Windhoekberg, from runoff and seepage after the 30 mm of rain that<br />

fell a fortnight previously. ......................................................................................... 98<br />

Figure 43. Flowers blooming and succulents growing on the gravel skirt below the<br />

north slope of the western Windhoekberg, after the 30 mm of rain that fell a fortnight<br />

previously. ............................................................................................................... 98<br />

Figure 44. A patch of succulent mesembryanthemums/vygies flowering on a patch of<br />

rocks and gravels at the crest of red dunes just south of Aggeneys, after the 30 mm<br />

of rain that fell a fortnight previously. Hoedkop on the left and Skelemberg on the<br />

right horizon. ........................................................................................................... 99<br />

Figure 45. A north-easterly view from Windhoekberg towards Springbok. Note the<br />

two main habitat types of the study: terrestrial to the left and rupiculous towards the<br />

right. ...................................................................................................................... 113<br />

Figure 46. A view of red dunes and their vegetation in the foreground. Skelemberg is<br />

on the right-hand side and in the distance Windhoekberg lies on the left-hand side.<br />

.............................................................................................................................. 114<br />

Figure 47. Typical natural rupiculous habitat on the unnamed hill near the farmhouse.<br />

.............................................................................................................................. 114<br />

Figure 48. Habitat on Skelemberg. Note the rupiculous habitat on the left and the red<br />

sand and dunes to the left. .................................................................................... 115<br />

Figure 49. Man-made rupiculous habitat in natural terrestrial habitat. Often many<br />

species use these structures for refuge. ................................................................ 115<br />

Figure 50. Man-made quarry on the western side of the study site. In the<br />

background is Windhoekberg. ............................................................................... 116<br />

Figure 51. A dry pan in the Koa River drainage line with Skelemberg on the left. .. 116<br />

Figure 52. A man-made dam in the Koa River drainage line, with Hoedkopberg in the<br />

background. .......................................................................................................... 117<br />

Figure 53. A view west from the man-made dam in the northeast corner of the study<br />

site. Note Hoedkopberg in the background. .......................................................... 117<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 10

Figure 54. An easterly view from Bobbejaansgat towards Windhoekberg. Note the<br />

cement weir and the pool of water in the foreground. Such artificial aquatic sources<br />

can create habitat for the Namaqua stream frog and other frog species. ............... 118<br />

Figure 55. A view to the west from Windhoekberg. Note the few quiver trees. The<br />

farmhouse is in the centre of the picture with flat terrestrial habitat surrounding it. On<br />

the left is Skelemberg and in the distance on the right lies Ghaamsberg. .............. 119<br />

Figure 56. Bibron’s tubercled gecko found on the study site. ................................. 127<br />

Figure 57. A giant ground gecko found on the study site. ...................................... 127<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 11

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE<br />

I, George Johannes Bredenkamp, Id 4602105019086, declare that I am the owner of<br />

Eco-Agent CC, CK 95/37116/23, and we (George Johannes Bredenkamp<br />

Id4602105019086, Ignatius Lourens Rautenbach Id4212015012005, Alan Charles<br />

Kemp Id4405075033081, Jacobus Casparus Petrus van Wyk Id6808045041084) and<br />

Lukas Jurie Niemand Id 7403125004084 furthermore declare that we<br />

• Are committed to biodiversity conservation but concomitantly recognize the need<br />

for economic development. Whereas we appreciate the opportunity to also learn<br />

through the processes of constructive criticism and debate, we reserve the right<br />

to form and hold our own opinions and therefore will not willingly submit to the<br />

interests of other parties, be it the client or the relevant competent authorities, or<br />

change our statements to appease them;<br />

• Abide by the Code of Ethics of the S.A. Council for Natural Scientific Profession;<br />

• Act as independent specialist consultants respectively in the fields of ecology,<br />

vegetation science and botany, as well as in mammalogy, ornithology,<br />

herpetology and as well as invertebrates;<br />

• Are assigned as specialist consultants by the <strong>SRK</strong> Group for the proposed<br />

project “A vegetation and vertebrate fauna diversity assessment for a<br />

photovoltaic power (PV) energy generation facility on Portion 3 of the farm<br />

Zuurwater 62, near Aggeneys, Northern Cape Province ” described in this report;<br />

• Do not have or will not have any financial interest in the undertaking of the activity<br />

other than remuneration for work performed;<br />

• Have or will not have any vested interest in the proposed activity proceeding;<br />

• Have no and will not engage in conflicting interests in the undertaking of the<br />

activity;<br />

• Undertake to disclose to the client and the competent authority any material<br />

information that have or may have the potential to influence the decision of the<br />

competent authority required in terms of the Environmental Impact Assessment<br />

Regulations 2006;<br />

• Will provide the client and competent authority with access to all information at<br />

our disposal, regarding this project, whether favourable or not.<br />

GJ Bredenkamp<br />

I. L. Rautenbach<br />

A. C. Kemp JCP van Wyk<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 12

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

Vegetation<br />

Although there are no statutory conservation area within this vegetation type, very<br />

little of the area has been transformed. A local exception is in the mine area close to<br />

Aggeneys, where mining infrastructure and mine dumps, and also residential areas,<br />

transformed some land.<br />

All the results indicate that the area is of biodiversity importance. However, the most<br />

important areas are the Inselbergs including their quartz gravel plateaus and foot<br />

slopes. The dry grassy plains are of relatively less biodiversity importance. Although<br />

the proposed development site is not located on the Inselbergs or quartz plains, it is<br />

still emphasized that these are considered as No-Go areas and should be protected.<br />

Any development on the property should be in accordance with the conservation<br />

policies of the relevant authorities.<br />

It is suggested that the proposed the development of proposed photovoltaic power<br />

generation facility be supported with the condition that the lay-out as shown in this<br />

document be strictly followed and no changes be done to the lay-out without<br />

consultation of the biodiversity specialists.<br />

Mammals<br />

Four pertinent matters emerge from the list of mammals compiled during the site visit<br />

and the subsequent desktop study:<br />

1. the species assemblage is typical of a western semi-arid region (particularly<br />

species such as the elephants shrew species, the ground squirrel, the spectacled<br />

dormouse, the various gerbil species, the dassie rat, whistling rats, the blackfooted<br />

cat, the bat-eared fox, the Cape fox, the gemsbok, the springbok etc.);<br />

2. the species richness of 56 is typical of an extensive area such as the property<br />

(5000 ha) and of adjoining areas, with a near-natural degree of connectivity;<br />

3. land-use practices and civilization pressures are geared to low-key grazing with a<br />

focus on concomitant floral conservation to benefit year-round grazing, which are<br />

conducive to species richness; and<br />

4. field observations suggested that population levels were low during the site visit.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 13

Population fluctuations are not uncommon, and often have a domino effect (for<br />

instance when prey population densities decrease in numbers, this will have an<br />

adverse effect on carnivore and raptor numbers).<br />

The rest of the species richness is made up from common and robust mammals with<br />

wide distributional ranges such as aardvarks, springhares, four-striped grass mouse,<br />

porcupines, the caracal, the genet, the two mongoose species, the black-backed<br />

jackal etc.<br />

The role of insectivorous bats in an ecosystem is often under-estimated, whereas<br />

their susceptibility to reigning environmental conditions is under-appreciated. Bats<br />

are sensitive to adverse daytime environmental conditions and predation, and<br />

suitable daytime roosting sites are of cardinal importance. Especially the<br />

Bobbejaansgat Mountain has many boulders and rock faces forming many<br />

overhangs and deep crevices suitable for daytime roosts. The dammed water and<br />

marshland conditions in the Koa River Wash to the north-east of the site are likely to<br />

support insect populations for hawking bats.<br />

The intended development will result in a progressive loss of ecological sensitive and<br />

important habitat units, ecosystem function e.g. reduction in water quality, loss of<br />

faunal habitat, and of loss/displacement of threatened or protected fauna. The main<br />

conservation objectives for mammals on Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater 62 are to<br />

retain untransformed the mountains and their gravel skirts, the deep red sands and<br />

dunes, and as much as possible of the Koa River washes and pans, and the<br />

untransformed adjacent grassy plains. The mountains, pans and dunes should be<br />

designated sensitive areas and excluded from any development, apart from low<br />

densities of livestock grazing.<br />

Birds<br />

The main conservation objectives for birds on Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater 63 are<br />

to retain untransformed the mountains and their gravel skirts, the deep red sands<br />

and dunes, and as much as possible of the Koa River washes and pans, together<br />

with whatever of the adjacent grassy plains is not transformed by the proposed solar<br />

PV electricity generation facility. The mountains, pans and dunes should be<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 14

designated sensitive areas and excluded from any development, apart from low<br />

densities of livestock grazing. Of 169 bird species recorded and/or expected on<br />

Zuurwater, nine are threatened species, of which the resident, near-endemic, habitatspecific<br />

and range-restricted Ludwig's Bustard and Red Lark are both considered<br />

Vulnerable by IUCN criteria. The PV array is not considered a direct threat to any<br />

bird species, given its limited impact in space (

1. PROJECT BACKGROUND<br />

South Africa, along with many other parts of the world, is experiencing a rising<br />

demand for various forms of energy, especially electricity. Traditionally, the country's<br />

electricity has been generated mainly by coal-fired power stations, plus a single<br />

nuclear energy plant. Coal is a non-renewable resource, and burning coal also adds<br />

to the rising threat of global warming, so South Africa is joining the worldwide trend to<br />

develop additional and renewable sources of energy. The arid western region of<br />

South Africa enjoys many days of clear unpolluted skies and hence one of the higher<br />

incidences of solar radiation in the world, making it an ideal area to invest in solar<br />

power generation.<br />

Figure 1. Map of solar radiation, showing the high levels of radiation expected in western<br />

South Africa (www.slc-group.net)<br />

The mining and mineral beneficiation industries are among the major consumers of<br />

electricity in South Africa, so placement of energy generation facilities as close as<br />

possible to such activities makes sense for both economic and power-distribution<br />

reasons. The farm Zuurwater 63 borders the property of the Aggeneys mining<br />

complex, in particular the Black Mountain Mining (Pty) Ltd zinc-lead-copper mines.<br />

These mines currently receive their electricity from the Eskom grid via an on-site<br />

transformer substation, and from here it is distributed to their shafts at Broken Hill,<br />

Swartberg, Big Syncline and Gamsberg.<br />

The proposed development is to generate 500MW of electricity daily using<br />

photovoltaic (PV, solar panel) power generation and is planned by Sato Energy<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 16

Holdings (SHE, Pty Ltd). The main components would be shipped to South Africa<br />

from Germany in containers before being transported to and erected on the site. SHE<br />

will use local contractors to produce the 'feet' of concrete slabs for the units, and to<br />

assist with erection and maintenance of the units and the terrain. SHE will purchase<br />

the property for the duration of the project, estimated at 30-40 years. The property is<br />

currently being used for low-density livestock grazing (sheep, goats, cattle, horses),<br />

typical of such a semi-arid area, and such activities will continue on the property<br />

alongside re-zoning of all or part of the land from agricultural to a different use.<br />

The c. 5,000 ha Portion 3 of the Farm Zuurwater 62 straddles the National N14 Road<br />

about 10 km east of the mining village of Aggeneys, 60 km west of Pofadder and 100<br />

km east of Springbok, in the Khai Ma Local Municipality of the Northern Cape<br />

Province. Most of the farm lies north of the road on flat to undulating terrain classified<br />

as part of the Bushmanland Sandy Grassland vegetation unit (NKb 4), with isolated<br />

mountains that create conditions for the Aggeneys Gravel Vygieveld (SKr 19, Mucina<br />

& Rutherford 2006).<br />

The proposed development is for 26 generation units, with each site capable of<br />

producing 19.5 MWp (megawatts of power), that all together would cover a total area<br />

of about 884 ha (18% of the farm's area) and produce about 500MWp of electricity<br />

daily. Each unit consists of 820 5-solar-panel-deep 'tables', with each table statically<br />

supported on metal legs and beams with the feet anchored on concrete slabs that<br />

rest on the ground surface. Each table is orientated to face due north, at an<br />

appropriate angle (25 o ) to capture as much sunlight as possible throughout the year,<br />

but with a gap between tables of 8.5 m (minimum 7.7 m) to ensure that one table<br />

does not cast shade on another in any of the sun's positions during its annual<br />

passage between the tropical meridians. Each generation unit covers a site of total<br />

area 33,83 ha.<br />

Each solar panel is 1,956 x 992 x 50 mm, can produce 280Wp and weighs 27 kg,<br />

with a total of 1,812,200 panels with a payload mass of almost 50 metric tons<br />

required for the whole development. The panels will be shipped from Germany in<br />

3,596 40' high-cube containers, each with a tare mass of c. 3,800 kg. The concrete<br />

'foot' slabs will be manufactured locally, and possibly the metal frameworks to<br />

support the panels.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 17

The original plan was for all units/sites/tables to be placed in one section of<br />

Zuurwater, ideal for connectivity and management, but during our assessments we<br />

detected various biodiversity sensitivities that suggested where possible alternative<br />

sites were needed for some of the tables.<br />

This report combines a 2-day site visit by the EcoAgent team (Vegetation Scientist<br />

mammalogist, ornithologist and herpetologist), on 27-28 June 2011; accompanied by<br />

the <strong>SRK</strong> Environmental Assessment Practitioners (EAPs) to assess the vegetation<br />

and vertebrate fauna and possible impacts of the development and to suggest<br />

possible mitigation options should it be approved.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 18

2. ASSIGNMENT<br />

Eco-Agent Ecological Consultants CC was appointed by <strong>SRK</strong> <strong>Consulting</strong> Engineers<br />

and Scientists to assess the vegetation and undertake a mammal, bird, reptile and<br />

amphibian study for the relevant portion of the Farm Zuurwater 62. This assignment<br />

is in accordance with the EIA Regulations (No. R.385, Department of Environmental<br />

Affairs and Tourism, 21 April 2006) emanating from Chapter 5 of the National<br />

Environmental Management Act 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998), as well as according to<br />

the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA, Act No. of 2002)<br />

The assignment is interpreted as follows: Compile a study of the vegetation, flora and<br />

vertebrate fauna of the site, with emphasis on Red Data plant and vertebrate species<br />

that occur or may occur on the site. In order to compile this, the following had to be<br />

done:<br />

2.1. Initial preparations:<br />

<br />

<br />

Obtain all relevant maps and information on the natural environment of the<br />

concerned area.<br />

This includes information on Red Data plant and vertebrate species that may<br />

occur in the area.<br />

2.2. Vegetation and habitat survey:<br />

<br />

<br />

List the plant species (trees, shrubs, grasses and herbaceous species)<br />

present for plant community and ecosystem delimitation.<br />

Identify potential red data plant species, alien plant species, and medicinal<br />

plants.<br />

2.3. Plant community delimitation and description<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Process data (vegetation and habitat classification) to determine vegetation<br />

types (= plant communities) on an ecological basis.<br />

Describe the habitat and vegetation.<br />

Determine the sensitivity of the site for biodiversity, veld condition and<br />

presence of rare or protected species.<br />

Prepare a vegetation map of the area.<br />

Prepare a sensitivity map of the plant communities present, if relevant.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 19

2.4. Faunal assessment<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Obtain lists of the Red Data vertebrates that can be expected in the area.<br />

Assess the quantitative and qualitative condition of suitable habitat for the<br />

Red Listed vertebrates that may occur in the area.<br />

Assess the possibility of Red Listed fauna being present on the study site.<br />

Compile a list of occurrences.<br />

2.5. General<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Identify and describe particular ecologically sensitive areas.<br />

Identify problem areas in need of special treatment or management, e.g. bush<br />

encroachment, erosion, water pollution, degraded areas, reclamation areas.<br />

Make recommendations on aspects that should be monitored during<br />

development.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 20

3. RATIONALE<br />

It is widely recognised that to conserve natural resources it is of the utmost<br />

importance to maintain ecological processes and life support systems for plants,<br />

animals and humans. To ensure that sustainable development takes place, it is<br />

therefore important that possible impacts on the environment are considered before<br />

relevant authorities approve any development. This led to legislation protecting the<br />

natural environment. In 1992, the Convention of Biological Diversity, a landmark<br />

convention, was signed by more than 90 % of all members of the United Nations. In<br />

South Africa, the Environmental Conservation Act (Act 73 of 1989), the National<br />

Environmental Management Act, 1998 (NEMA) (Act 107 of 1998) and the National<br />

Environmental Management <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Act, 2004 (Act 10 0f 2004) ensure the<br />

protection of ecological processes, natural systems and natural beauty, as well as<br />

the preservation of biotic diversity within the natural environment. They also ensure<br />

the protection of the environment against disturbance, deterioration, defacement or<br />

destruction as a result of man-made structures, installations, processes, products or<br />

activities. In support of these Acts, a draft list of Threatened Ecosystems was<br />

published (Government Gazette 2009), as part of the National Environmental<br />

Management <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Act, 2004 (Act 10 of 2004), and these Threatened<br />

Ecosystems are described by SANBI & DEAT (2009). International and national Red<br />

Data lists have also been produced for various plant and animal taxa.<br />

All components of the ecosystems (physical environment, vegetation, animals) at a<br />

site are interrelated and interdependent. A holistic approach is therefore imperative<br />

to include effectively the development, utilisation and, where necessary, conservation<br />

of the given natural resources into an integrated development plan, which will<br />

address all the needs of the modern human population (Bredenkamp & Brown 2001).<br />

It is therefore necessary to make a thorough inventory of the plant communities and<br />

other biodiversity on the site, in order to evaluate the biodiversity and possible rare<br />

species. This inventory should then serve as a scientific and ecological basis for the<br />

planning exercises and the subsequent development.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 21

This development of a PV generation facility close to the mining complex of<br />

Aggeneys is obviously optimal for SATO/SEH essential for the facility to proceed. If<br />

the development can proceed without any significant addition to the environmental<br />

impacts on the least sensitive grazing areas of the livestock farm, then it is also<br />

strategically important for the adjacent mine(s) in the light of national energy planning<br />

and concerns.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 22

4. SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY<br />

• To identify and map the vegetation units as ecosystems that occur on the<br />

site,<br />

• To assess the ecological sensitivity of these ecosystems comment on<br />

ecologically sensitive areas, in term of their biodiversity and where needed<br />

ecosystem function<br />

• To assess qualitatively and quantitatively the significance of the habitat<br />

components and current general conservation status of the site,<br />

• To comment on connectivity with natural vegetation and habitats on adjacent<br />

sites,<br />

• To recommend suitable buffer zones, if relevant,<br />

• To provide a list of plant and vertebrate fauna species that do or might occur<br />

on site and that may be affected by the development, and to identify species<br />

of conservation concern,<br />

• To highlight potential impacts of the proposed development on vegetation,<br />

fauna and flora of the study site, and<br />

• To provide management recommendations that might mitigate negative and<br />

enhance positive impacts, should the proposed development be approved.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 23

5. STUDY AREA<br />

5.1 Regional setting<br />

Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater 62 is situated in the flat, open habitats of the<br />

Bushmanland area of the Northern Cape Province (Figures 2-4). Most of the farm is<br />

situated just north of the N14 National Road, and about 10 km southwest of the<br />

mining complex of Aggeneys (Fig. 5). Its drainage systems, red sand dunes and<br />

scattered rocky mountains forms the south-western edge of the Gariep (Orange)<br />

River catchment, Kalahari semi-desert, and Bushmanland granite topography, and its<br />

climate is at the eastern edge of the winter rainfall areas.<br />

Figure 2. The locality of the SATO/SHE property, Portion 3 of the Farm Zuurwater 63, in<br />

relation to Aggeneys, the N14 National Road and the Koa River drainage system.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 24

Figure 3. Satellite image showing the location of Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater 63 (purple<br />

line), in relation to the N14 National Road and the currently dominant drainage line of the Koa<br />

River wash. Aggeneys mines and villages are situated in and below the hills just above the<br />

N14 sign.<br />

Figure 4. Satellite image of Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater 62 (purple lines), in relation to the<br />

general area around Aggeneys and the route of the N14 National Road.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 25

Figure 5. Satellite image of Portion 3 of the farm Zuurwater 62 (purple lines), showing the<br />

principal features of and names for the topography, habitats and relevant neighbouring<br />

features.<br />

5.2 Physical Environment<br />

Regional Climate<br />

The mean annual precipitation is 99 mm, with a high annual coefficient of variation<br />

(40%). Rain can fall in any month but is mainly in the later austral summer, peaking<br />

in February-April. However, mean annual evaporation potential exceeds rainfall<br />

almost 30-fold, so mean annual soil moisture stress is high (87%). Mean annual<br />

temperature is 17.3 o C, but mean monthly temperatures exceed 30 o C in mid-summer<br />

and drop close to zero in mid-winter, with 21 mean frost days annually.<br />

Geology<br />

The general area is formed mainly of eroded Quaternary sediments, sands and<br />

calcretes, overlain in some areas with aeolian red Kalahari sands. The harder<br />

igneous intrusions of the Bushmanland quartzites protrude at scattered localities,<br />

eroded into the gravel patches found around their bases and spread along drainage<br />

lines.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 26

Topography and drainage<br />

The topography is generally flat and open, except for the few quartzite mountains<br />

and, given the low rainfall, recent drainage lines that are relatively lightly incised and<br />

shallow. The area does form part of the palaeo-drainage system of the Gariep River<br />

basin, evident on and around the site as the rather ill-defined Koa River wash(es)<br />

and some of their pans (Figs 2-5). The mountains on site generally have their<br />

steepest and coolest sides facing southwest, into the prevailing wind, and their<br />

warmest and less steep sides facing northeast, with associated effects on the<br />

biodiversity on either side.<br />

Soil<br />

Much of the area is covered in deep (up to 30 cm) red sands, forming scattered<br />

and/or fields of red dunes in places most subject to the prevailing southwest wind<br />

and with structures that impede their movement (Fig. 5). The quartzite gravels occur<br />

in three main forms, small fine-grained patches on the tops and foothills of the<br />

mountains, more variable and widespread sizes around the erosion zones below the<br />

mountains, and small feldspar patches (with pink Hoogoor Suite gneiss evident), with<br />

calcrete gravels also emerging in a few patches where exposed by erosion on the<br />

flats. The effects of the mountains, plus the prevailing winds, result in sand and<br />

dunes accumulating mainly on their southern foothills, or in channels between them,<br />

with more exposed and gravelly plains forming in their northeast lee.<br />

Land Use<br />

The only agricultural land use is livestock grazing at low densities (?about 4 large<br />

stock units (LSU)/100 ha), with sheep, cattle and goats currently present on site. A<br />

few game animals (springbok, ostrich) also occur.<br />

5.3 Vegetation Types<br />

The main vegetation type on site is classified as the Bushmanland Sandy Grassland<br />

vegetation unit (NKb 4), with the isolated mountains creating conditions for the<br />

Aggeneys Gravel Vygieveld (SKr 19, Mucina & Rutherford 2006).<br />

The Khai Ma local municipality (KMLM) lies to the east of the Richtersveld and<br />

contains virtually the entire extent of the Bushmanland Inselberg priority area - one of<br />

the nine zones identified through the SKEP process as important conservation areas<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 27

in the Succulent Karoo (Marsh et al. 2009). It comprises the eastern part of the<br />

Gariep Centre of Plant Endemism, which includes the Koa river valley to the north<br />

and the mountainous terrain to the south east. The area experiences summer rainfall<br />

patterns, and is characterized by an expansive, undulating landscape. The area is<br />

dominated by a plain of dry grasslands with scattered ancient rocky outcrops, named<br />

Inselbergs. These Inselbergs are important refugia for plants and animals and act as<br />

steppingstones for rock-loving species migrating east west across the sand-covered<br />

plains of Bushmanland. The isolation of populations has led to diversification within<br />

the dwarf succulent shrublands, creating remarkable local populations of plant life<br />

(Marsh et al. 2009). The KMLM spans across practically the entire extent of the<br />

Bushmanland Inselberg priority area identified through the SKEP process – and thus<br />

consists of a unique and dynamic region that contains many rare and fragile habitat<br />

types, including the fine grain quartz patches found on the plateau’s - and in the case<br />

of the Gamsberg and Achab - on the mountain apron. These unique and confined<br />

areas are host to a remarkable number of endemic plants (Marsh et al. 2009).<br />

The Gariep-Koa River Watershed marks the highest point in the Bushmanland. Most<br />

of the Inselbergs make up this SE-NW watershed. A number of drainage basins exist<br />

to the north and south of this watershed. Maintaining the integrity of these drainages<br />

is essential as they play an important role in the structure and dynamics of specific<br />

habitats and populations.<br />

5.4 The Study Site for the Proposed Development<br />

The general location of the property on which the development is planned (Portion 3<br />

of the farm Zuurwater 62) is described and illustrated above (Figures 2-4). Within this<br />

property, a preliminary on-site assessment suggested that the least sensitive habitats<br />

and biodiversity lay just west of the N14 National Road (and the eastern farm<br />

boundary), with some additional, slightly more sensitive, and possible alternative<br />

sites adjacent to the main area (Figure. 6).<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 28

Figure 6. Close-up satellite image of the east-central section of Portion 3 of the farm<br />

Zuurwater 62 (cf. Figures 2-4), showing the principal habitat and topographical features<br />

influencing the identification of this site as ecologically of low sensitivity but still<br />

technologically and socially suitable. The least ecologically sensitive sector of the<br />

development (1, thick dark blue line) is proposed for west of the N14 (yellow line), with<br />

adjacent slightly more sensitive extensions, including east of the N14 (2, shaded pale blue),<br />

and an even less preferable north-western extension (3, thin dark blue line).The route of a<br />

high-voltage transmission line and pylons (green lines) is also shown, from the Eskom<br />

substation to the east to Springbok in the west. The eastern boundary of Zuurwater is also<br />

shown (purple line). Engineers will present a final footprint, outline and spacing for how to fit<br />

the 5-panel table arrays into minimum non-sensitive space available and as close as possible<br />

to the Eskom substation. Access to a water pipeline between Zuurwater farmhouse and<br />

Aggeneys also has to be accommodated.<br />

The exact form and location of the development will require accommodation of the<br />

surface area necessary to generate 500 MW of electricity, in the conformation<br />

essential to capture maximal solar radiation, and so no GPS coordinates that<br />

spatially define the study site are offered. The principal factors for the solar panels<br />

are that they must face north, at the best angle to capture sunlight for that latitude,<br />

and with sufficient space between 'tables' to exclude any shading of one another<br />

during the sun's annual traverse. The tables for this project have been designed for a<br />

minimal footprint overall, with tables 5 panels deep (length depending on site<br />

conformation) and 8 m between table rows.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 29

Figure 7. Impression of how solar panel tables are arranged and spaced, but note this is only<br />

a 2-deep panel array, supported on a single leg/foot line embedded in the ground and with<br />

only a narrow space between tables (from www.slc-group.net). The Zuurwater design calls for<br />

a 5-deep array, supported on a 2-feet line and bolted to a concrete slab resting on the ground<br />

surface, and with an 8 m shade gap between tables.<br />

Figure 8. View of power connection and distribution cables housed under the solar panel<br />

tables. The design allows small livestock to graze under and around the tables (sheep, but<br />

not goats, cattle or horses on Zuurwater). The upper surfaces of the solar panels are washed<br />

automatically with water at appropriate intervals, and the waste runs into collection channels<br />

for recycling (from www.slc-group.net).<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 30

6. METHODS<br />

Prior to the field visits, a desktop study of the available literature and relevant reports<br />

was made.<br />

The EcoAgent team (Prof G.J. Bredenkamp (vegetation scientist) Dr I.L. Rautenbach<br />

(mammalogist), Dr A. Kemp (ornithologist) and Mr J.C.P. van Wyk (herpetologist).<br />

Conducted a site visit on 27-28 June 2011; accompanied by the <strong>SRK</strong> Environmental<br />

Assessment Practitioners (Ms Lyn Brown and Dr Jenny Lancaster ). The available<br />

roads on the site were driven using a 4x4 pick-up. The farm owner, Mr Deon<br />

Maasdorp and his family (and Hester, Olivia, Waldo and Dayle) guided the EcoAgent<br />

team on site, and Ms Jennifer Brown (SATO) and technology consultant Mr Alfred<br />

Ostenreid (SLC Group) advised on details of the development.<br />

Regular stops were made to record diversity and veld conditions by walking random<br />

transects. Coordinates were taken at localities of note.<br />

6.1. Flora<br />

6.1.1 Vegetation and flora<br />

The vegetation was stratified into relatively homogeneous units on recent aerial<br />

photographs of the area. At several sites within each homogeneous unit a description<br />

of the dominant and characteristic species was made. These descriptions were<br />

based on total floristic composition, following established vegetation survey<br />

techniques (Mueller-Dombois & Ellenberg 1974; Westhoff & Van der Maarel 1978).<br />

Data recorded included a list of the plant species present, including trees, shrubs,<br />

grasses and forbs. Comprehensive species lists were therefore derived for each<br />

plant community / ecosystem present on the site. These vegetation survey methods<br />

have been used as the basis of a national vegetation survey of South Africa (Mucina<br />

et al. 2000) and are considered to be an efficient method of describing vegetation<br />

and capturing species information. Notes were additionally made of any other<br />

features that might have an ecological influence.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 31

The identified systems are not only described in terms of their plant species<br />

composition, but also evaluated in terms of the potential habitat for red data plant<br />

species.<br />

Red data plant species for the area were obtained from the SANBI data bases, with<br />

updated threatened status, (Raimondo et al. 2009). These lists were then evaluated<br />

in terms of habitat available on the site, and also in terms of the present development<br />

and presence of man in the area.<br />

Alien invasive species, according to the Conservation of Agricultural Resources Act<br />

(Act No.43 of 1983) as listed in Henderson (2001), are indicated.<br />

Medicinal plants are indicated according to the PRECIS list of SANBI, and is<br />

obtained from Smit (2007).<br />

The field observations were supplemented by literature studies from the area<br />

(Coetzee et al. 1994, 1995).<br />

6.1.2 Plant Conservation Priority<br />

The following conservation priority categories were used for each site:<br />

High: Ecologically sensitive and valuable land with high species richness<br />

and/or sensitive ecosystems or red data species that should be<br />

conserved and no developed allowed.<br />

Medium-high: Land where sections are disturbed but which is in general<br />

ecologically sensitive to development/disturbances.<br />

Medium:<br />

Medium-low:<br />

Low:<br />

Land on which low impact development with limited impact on the<br />

vegetation / ecosystem could be considered for development. It is<br />

recommended that certain portions of the natural vegetation be<br />

maintained as open space.<br />

Land of which small sections could be considered to conserve but<br />

where the area in general has little conservation value.<br />

Land that has little conservation value and that could be considered<br />

for developed with little to no impact on the vegetation.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 32

6.1.3 Sensitivity<br />

Only High and Low sensitivity must be indicated. No development should be allowed<br />

on High sensitive areas.<br />

In terms of sensitivity the following criteria applies:<br />

High: High and Medium-High conservation priority categories mentioned<br />

above are considered to have a High sensitivity and development<br />

should not be supported.<br />

Low:<br />

Medium, Medium-Low and Low conservation priority categories<br />

mentioned above are considered to have a Low sensitivity and<br />

development may be supported. Portions of vegetation with a<br />

Medium conservation priority should be conserved.<br />

Plant species recorded in each plant community with an indication of the status of the<br />

species by using the following symbols:<br />

A = Alien woody species<br />

D = Dominant<br />

d = subdominant<br />

G = Garden or Garden Escape<br />

M = Medicinal plant species<br />

P = Protected trees species<br />

p = provincially protected species<br />

RD = Red data listed plant<br />

W = weed<br />

6.2. Mammals<br />

The site visit was conducted on 27-28 June 2011. During this visit the observed and<br />

derived presence of mammals associated with the recognized habitat types of the<br />

study site, were recorded. This was done with due regard to the well recorded global<br />

distributions of Southern African mammals, coupled to the qualitative and<br />

quantitative nature of recognized habitats.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 33

6.2.1. Field Survey<br />

During the site visits mammals were identified by visual sightings through random<br />

transect walks and patrolling with a vehicle. No trapping or mist netting was<br />

conducted, as the terms of reference did not require such intensive work. In addition,<br />

mammals were also identified by means of spoor, droppings, burrows or roosting<br />

sites.<br />

Three criteria were used to gauge the probability of occurrence of vertebrate species<br />

on the study site. These include known distribution range, habitat preference and the<br />

qualitative and quantitative presence of suitable habitat.<br />

6.2.2. Desktop Survey<br />

As many mammals are either secretive, nocturnal, hibernators and/or seasonal,<br />

distributional ranges and the presence of suitable habitats were used to deduce the<br />

presence or absence of these species based on authoritative tomes, scientific<br />

literature, field guides, atlases and data bases. This can be done with a high level of<br />

confidence irrespective of season.<br />

The probability of occurrences of mammal species was based on their respective<br />

geographical distributional ranges and the suitability of on-site habitats:<br />

• High probability would be applicable to a species with a distributional range<br />

overlying the study site as well as the presence of prime habitat occurring on<br />

the study site. Another consideration for inclusion in this category is the<br />

inclination of a species to be common, i.e. normally occurring at high<br />

population densities.<br />

• Medium probability pertains to a mammal species with its distributional<br />

range peripherally overlapping the study site, or required habitat on the site<br />

being sub-optimal. The size of the site as it relates to its likelihood to sustain<br />

a viable breeding population, as well as its geographical isolation is also<br />

taken into consideration. Species categorized as medium normally do not<br />

occur at high population numbers, but cannot be deemed as rare.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 34

• Low probability of occurrence will mean that the species’ distributional range<br />

is peripheral to the study site and habitat is sub-optimal. Furthermore, some<br />

mammals categorized as low are generally deemed to be rare.<br />

6.2.3. Specific Requirements<br />

During the site visits, the site was surveyed and assessed for the potential<br />

occurrence of Red Data and/or wetland-associated species such as: Juliana’s golden<br />

mole (Neamblosomus juliana), Highveld golden mole (Amblysomus septentrionalis),<br />

Rough-haired golden mole (Chrysospalax villosus), African marsh rat (Dasymys<br />

incomtus), Angoni vlei rat (Otomys angoniensis), Vlei rat (Otomys irroratus), Whitetailed<br />

rat (Mystromys albicaudatus), Forest shrew (Myosorex varius), Short-eared<br />

trident bat (Cloeotis percivali), African clawless otter (Aonyx capensis), Spottednecked<br />

otter (Lutra maculicollis) and Marsh mongoose (Atilax paludinosus).<br />

6.3. Birds<br />

I made a 2-day site visit on 27-28 June 2011 as part of an EcoAgent team, led by<br />

Prof G.J. Bredenkamp (botanist), comprising Dr I.L. Rautenbach (mammalogist) and<br />

Mr J.C.P. van Wyk (herpetologist), and in the company of the farm owner Mr Deon<br />

Maasdorp. The visit was made in mid-winter, after Palaearctic and intra-African<br />

migrant bird species had departed. The weather during the visit was cold at night and<br />

cool during the day, under clear mild clear conditions and with only a slight breeze.<br />

Good rains had fallen the previous summer, after a 3-year drought, and unusually<br />

heavy rains of 30 mm had fallen two weeks before the survey, inducing some<br />

unexpected plant growth and flowering.<br />

During a site visit, selected roads and tracks on the site were driven, with regular<br />

stops made to record plant and vertebrate diversity and habitat types by walking<br />

random transects. Coordinates were taken at localities of note, and attention was<br />

also paid to the biological conditions and diversity within at least 500 meters on<br />

adjoining properties.<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 35

6.3.1 Bird Habitats<br />

While bird distributions have been related to broad vegetation types, there is a<br />

general consensus internationally that vegetation structure, rather than floral<br />

composition, is the most critical parameter in most bird habitat preferences (Allan et<br />

al. in Harrison et al. 1997). The principal vegetation units identified for birds in South<br />

Africa, based primarily on similarity in vegetation structure rather than composition,<br />

are divided into four major groups Karoo (subdivided into Succulent, Nama and<br />

Grassy), Grassland (Sweet, Mixed, Sour and Alpine) Kalahari (South and Central),<br />

and Woodland (Arid, Moist and Mopane), plus the discrete and smaller areas of<br />

Fynbos, Valley Bushveld, East Coast Littoral and Afromontane Forest habitat<br />

(Allan et al. in Harrison et al. 1997).<br />

Of course vegetation structure is determined by and offers a surrogate for a wide<br />

variety of abiotic factors (of which climate, in South Africa, particularly rainfall and<br />

temperature, are most important). The habitats occupied by flying birds differ from<br />

those of most terrestrial vertebrates in being three-dimensional, especially for aerialfeeding<br />

species and those regularly using the airspace above landscapes with low<br />

relief and/or short vegetation, but in the two horizontal dimensions birds depend most<br />

on vegetation structure and substrate texture and colour (except of a minority of<br />

species with particular food/nest requirements of substrate, foliage, flowers, fruit or<br />

seeds). Although plant species composition is the main criterion used to delimit most<br />

vegetation biomes and units described for South Africa, the most recent analyses<br />

also take into account and offer good synopses of such abiotic factors that underlie<br />

these divisions as landscape structure and topography, geology and soil types, and<br />

climate, besides details of the flora and its conservation (Mucina & Rutherford 2006).<br />

The principal habitats on site were identified and stratified into relatively<br />

homogeneous units on recent satellite (Google Earth) images of the area, including<br />

any particular natural features and/or indications of transformed habitats (croplands,<br />

mining, buildings). Within each homogeneous unit, a description was made,<br />

illustrated by images, of the principal features that might influence bird distribution<br />

(vegetation structure, composition, quality and extent; water-related moist patches,<br />

marshes (vleis) and areas of open water; topographical and geological features such<br />

as cliffs, steep slopes, deep valleys or rocky outcrops; or man-made plantations or<br />

structures that might provide roost/nest sites).<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 36

The biodiversity significance of an area relates to its species diversity, endemism (of<br />

species or ecological processes) and significant occurrence of threatened/legallyprotected<br />

species or ecosystems. The following conservation priorities were used for<br />

each avian habitat type recognised on site or nearby:<br />

High: Ecologically sensitive and valuable land, with high species richness,<br />

sensitive ecosystems or Red Data species, that should be conserved<br />

and no development allowed.<br />

Medium-high: Land where sections are disturbed but that is still ecologically<br />

sensitive to development/disturbance.<br />

Medium:<br />

Medium-low:<br />

Low:<br />

Land on which low-impact development with limited impact on the<br />

ecosystem could be considered, but where it is still recommended<br />

that certain portions of the natural habitat be maintained as open<br />

spaces.<br />

Land on which small sections could be considered for conservation<br />

but where the area in general has little conservation value.<br />

Land that has little conservation value and that could be considered<br />

for developed with little to no impact on the habitats or avifauna.<br />

Only High or Low sensitivity is indicated for the habitats, with no development<br />

allowed on areas of High sensitivity, applying the following criteria:<br />

High: High and Medium-High conservation priority categories mentioned<br />

above are considered to have a High sensitivity and development<br />

should not be supported. These include sensitive ecosystems with<br />

low inherent resistance and/or resilience to disturbance factors, or<br />

highly dynamic systems important for maintenance of ecosystem<br />

integrity. Most such systems represent ecosystems with high<br />

connectivity to other important ecological systems or support high<br />

species diversity and provide suitable habitat for a number of<br />

threatened or rare species.<br />

Low:<br />

Medium, Medium-Low and Low conservation priority categories<br />

mentioned above are considered to have a Low sensitivity and<br />

development may be supported. Portions of habitat with a Medium<br />

conservation priority should be conserved as open areas and/or<br />

SATO Aggeneys July 2011 37

uffers wherever possible. These are slightly modified systems that<br />

occur along disturbance gradients of low-medium intensity, with<br />

some degree of connectivity with other ecological systems or<br />

ecosystems with intermediate levels of species diversity that include<br />

potential ephemeral habitat for threatened species. Low sensitivity<br />

habitats are degraded, highly disturbed and/or transformed systems<br />

with little ecological function and low species diversity.<br />

6.3.2 Bird Species<br />

On the site visit(s) I recorded the presence of bird species, or assessed the<br />

probability of their occurrence based on the habitat types recognized on and around<br />

the study site. This was done with due regard to the well-recorded general<br />

distributions of southern African birds at the quarter-degree grid cell (QDGC) scale<br />

(SABAP 1, Harrison et al. 1997) or the pentad (5’ lat. x 5’ long) scale (SABAP 2, ongoing,<br />

Animal Demography Unit website www.adu.org.za), coupled to my<br />

assessment of and experience with the qualitative and quantitative nature of the<br />