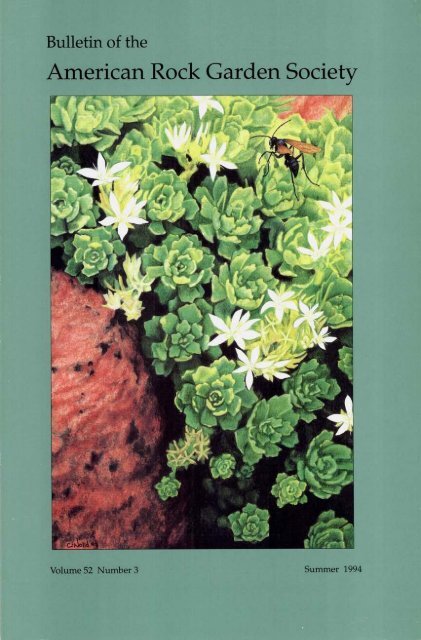

Bulletin - Summer 1994 - North American Rock Garden Society

Bulletin - Summer 1994 - North American Rock Garden Society

Bulletin - Summer 1994 - North American Rock Garden Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

On the Track ofDaphne arbusculaby Joan Means^A^hen they heard of our plans tojoin a botanic group visiting the Czechand Slovak Republics during the summerof 1993, our friends had two questions:"Are you sure you'll be safe?"and "Will you buy me one of thoseyellow spring gentians that the Czechsgrow so well?"But Czechoslovakia was not Bosniaor even Miami. Although the countrydivided its name and territory only sixmonths before our visit, it was an amicabledivorce. Yes, sometimes wecrossed the border between these twosmall Central European nations severaltimes in a single day, and each timewe had to show our passports tofuzzy-cheeked guards who wore armbandsbecause their uniforms hadn'tyet arrived. And, no, we couldn't buyGentiana verna var. oschtenica. Wedidn't visit any nurseries, and wedidn't even visit rock gardens, exceptone owned by an abashed forestranger—though in several cottage gardenswe did see Trillium grandiflorumgrowing under apricot trees just a fewfeet away from carrots and leeks, notto mention Papaver somniferum, universallygrown to provide poppy seed fordelicious rolls and pastries.Our trip was upcountry, to the ruralparts of these countries that few foreignershave visited. Farmland waspunctuated by small villages, theirhouses surrounded by gardens containingeverything from Albertaspruce to chickens, their streets decoratedwith red floribunda roses—andby loudspeakers on poles. These originallyrelayed government announcements,but apparently they've beenkept so that residents withoutWalkmans can enjoy music while theywork. Usually we stayed in smalltowns with well-stocked state supermarkets,private shops with ratherbare shelves, old churches, beer halls,and medieval buildings in the processof restoration. We could easily havespent our time sightseeing, but we'djoined a group from the New EnglandWild flower <strong>Society</strong> in hopes of seeingDaphne arbuscula in the wild. And wedid find that enchanting miniatureshrub—but not until we'd seen a greatmany other wonderful plants.Happily, we were in the hands of E-Tours, a Czech firm which is carvingout a niche in special-interest tours—bird-watching, farm practices, wineproduction, etc. For nearly three163

weeks, starting in late June of 1993, wecrisscrossed the Carpathian Mountains,and everywhere we were joinedby local botanists and conservationistsready to help us identify the plants wewere seeing. This was important,because it was too late in the year tolocate many familiar alpines by theirflowers. Still, other small plants ofgreat interest were in bloom, and theyweren't all on the tops of tall peaks.Indeed, because most of our groupwas interested in ferns and orchids,we had the pleasure of exploringplaces most rock gardeners mighthave bypassed: fields where pink andcream scabiosas bloomed along withthyme and teucrium; magnificentbeech forests carpeted with Soldanellaand Hepatica; limestone cliffs studdedwith campanulas and, yes, Daphnearbuscula.To fully appreciate our experience,you must meet the tour's cast of characters:Paul—our <strong>American</strong> leader, is a lectureron wildflowers who told E-Tourshe was bringing his "botany students"to study the flora. Naturally theCzechs expected a group of youngadults, so you can imagine the consternationfelt byBorek—a 27-year-old Czech with adegree in forestry, who served as theE-Tours agent and as our interpreter.Though urbane and charming, heclearly was surprised when he firstsaw...The 16 Students—most of us well pastretirement age. At least two wereclearly along just for the ride, onerecovering from a hip operation, andanother an octogenarian unable towalk without a cane. (Give us an hourfor shopping in a little town, though,and these two would beat the rest ofus to the stores.) As for young Borek,he spent his evenings switching ourreservations from youth hostels tomore "appropriate" quarters and persuadingbotanists that, no, our groupreally couldn't manage eight-hourtreks over the peaks of the HighTatras. His right-hand man was...Frank—champion bus driver of theCzech Republic (I couldn't possiblymake this up). Because he was practicingfor the international competitionto be held in Finland in August, Franktended to put the pedal to the metalon the straights, but he could wheelhis big bus over precipitous, ruttedlumber roads where I would haveopted for a Jeep. Despite a penchantfor flirting with pretty girls and breakinginto folk songs, this 30-somethingnative Slovak was a mother hen, constantlyworrying about our comfortand welfare. When, on the second fullday of the trip, my interest in orchidshad been so dampened by a downpourthat I returned to the bus, Franktook one look at my soggy jeans andsaid, "You take off." I'm past the agethat excites general male interest, but,not knowing him well, I declined,although he made his intentions clearerby offering me a dry pair of his ownsweat pants.Finally, there was the bus—large forour small group, washed daily byFrank, it was equipped with a smallrefrigerator to keep bottles of the magnificentlocal beer and the execrablelocal soft drinks cold. It did not, however,have a toilet. "Why can't you usenature, as we do?" asked youngBorek. Beech forests are markedlydeficient in underbrush, so we campaignedfor less exposed facilities. Nodoubt Borek will tell his grandchildrenabout the day he escorted a dozen<strong>American</strong> ladies to a public loo164 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

ecause, having failed to get us to abank during the unpredictable workinghours, he was the only one withcoins in the right currency.Natural functions aside, pollution isa major problem in both countries. Tokeep rural populations employed, thecommunists scattered factories everywhere—eventiny towns had at leastone high-rise block of apartments forworkers. As a result, most rivers arefull of industrial chemicals, not tomention sewage. In short, they arewhere the USA was 30 years ago. Still,we were struck by environmentalefforts that don't require large capitaloutlays. Forests are selectively cut orclear cut only in very narrow bands;landfills are promptly capped with alayer of earth; even when they havetractors, farmers use horse-drawnmachinery and hand labor to reduceerosion on steep slopes. Most impressive,as land is returned to privateownership, and it becomes clear thatthe heirs don't want to farm, smallconservation groups are buying uptracts to save them from development.Many of the glorious meadows andwoodlands we visited, especially inthe Czech Republic, were in the handsof these miniature nature conservancies.As mountains go, most of theCarpathians are small potatoes, justlow, wooded hills, which east of theDanube sweep in a great half-moonfrom Hungary to Poland to theUkraine. Composed of limestone thatin some places has been carved bystreams into spectacular caves, gorges,and pinnacles—usually crowned bythe ruin of a castle—they boast a florathat seems to owe as much to centuriesof farming and timbering as togeographical location. Indeed, theopen fields looked like herbaceousborders, and, where they are conservationland, they are carefully cut byscythe to preserve late-ripening seed. Iespecially remember, in damp meadows,red and pink orchids (Dactylorhizamajalis and Platanthera chlorantha)mixed with spikes of Gladiolus imbricatus,underplanted by the leaves ofColchicum autumnale and Primula veris.Drier fields were colorful with tall,purple salvias and yellow verbascums,the pink cluster-heads of Dianthuscarthusianum, and cream Scabiosaochroleuca, among too many others tomention. Nearly every open placeboasted a trio of ubiquitous campanulas:lavender C. persicifolia, purple C.glomerata, and mauve C. patula. Lesswell known, the third is a short-livedcharmer with up-facing bells. Shadierspots at the edge of woodlands wererich with yellow and purple aconites,Campanula trachelium, the attractivewhite buttercups of Ranunculus plantanifolius(longer stemmed than itscousin, R. aconitifolius), Lilium martagon(we saw only one white one), andlO'-tall spikes of Delphinium elatum(Foerster cultivars are available inGermany). The white plumes ofAruncus Sylvester filled the narrow cutsmade by selective timbering. Even theforest floors were gardens: there wereferns, of course, but also Paris quadrifolia(a trillium relative), Asarumeuropeum growing mixed with Hepaticanobilis and lily-of-the-valley, Convallariamajalis.Confusingly, the small plants treasuredby rock gardeners often showedup among border plants. Adonis vernalisand the alpine thistle, Carlinaacaulis, nestled among tall campanulasin dry meadows; encrusted saxifragescovered limy outcrops only inchesfrom the tall spires of Digitalis grandiflora;and a mat of 6" stems bearingracemes of spectacular purple bells—acampanula we weren't able to identify—grewin a hay field.On the Track of Daphne arbuscula 165

After the gardenesque comfort ofthe western Carpathians, the brutallyglaciated granite peaks of Slovakia'sHigh Tatras came as a shock. We hadtraveled along the highly industrializedVah River to the city of Poprad,where chemical plants belched fumesover a high plain. And there in the distance,thrusting into the sky as abruptlyas the Grand Tetons, was a smallcluster of rugged peaks: at 8,500',much taller than we ever imagined,yet occupying not much more territorythan the island of Manhattan. TheHigh Tatras is a national park and alsoan enormously popular tourist and skiresort—both the Czech Republic andSlovakia are incredible vacation bargainsfor most Europeans.We frittered away most of a morningon still another Dactylorhiza besidethe road, but finally, about noon, a fewof us started up a trail with severalthousand tourists and the parkbotanist, Dr. Rudolf Soltes, a burlyman who is an eminent expert onlichens. We hadn't even entered thewoods before we saw one of the outstandingplants of our trip: Campanulatatrae, a bellflower in the rotundifoliacomplex (photo, p. 223). This onemakes a neat clump and has sumptuouspurple bells hanging in profusionon sturdy, 6" stems; apparently, it isnot in general cultivation—but shouldbe. The trail rose through the forest—we nearly stumbled over a Soldanellacarpatica nestled among the rocks—and wound into a stand of mughopines, where the purple-spotted yellowflowers of 18"-tall Gentiana punctatawere magnificent. Eventually, thepath emerged on a gentle alpinemeadow of turf and willows. Beyond,the path to a hanging valley and lakewas blocked by a cliff that had beendraped with what looked like a cargonet. Anyone wishing to climb up hadto pay a fee to a park functionary.By then, only Borek was with us."Joan, I don't think you should go farther,"he said. I didn't think so either,so we contented ourselves with theplants at hand. Campanula alpinacaught our attention immediately(photo, p. 222). Huddled against bouldersout of the wind, it had furry littleleaves and 4" stems carrying severallarge, purple bells, The last few goldbossed,white cups of Pulsatilla alpinanodded in the wind; glistening whitedaisies of Chrysanthemum (Leucanthemopsis)alpinum hugged the ground;and along the brook tumbling from thehanging lake, mats of the rather succulentleaves of Arabis alpina were toppedby long-stemmed white flowers.Paul was afraid of ski lifts, so six ofus interested in alpine plants left thegroup the next day to ride a chair tojust below the snow line. There wasanother fee for those wishing to hikethe trail to a lake, but we were happyenough crawling over a steep slope ofturf and scree, as Borek and Frankwatched over us like sheep dogs fromthe lift terminus. With the added altitude,we found pulsatillas newlyopened, along with the glisteningwhite, multi-flowered inflorescences ofAnemone narcissiflora (photo, p. 222). Apatch of Silene acaulis mingled with ahandsome plant new to me, Pedicularisverticillata, with typical ferny foliageand, on stems only a few inches high,heavy little spikes of brilliant pinkflowers (photo, p. 223). A very different,classic alpine was far less conspicuous.We'd been kneeling on it, and itsmossy matrix, for an hour before werealized that the dime-sized rosettes ofshiny, little, notched leaves were thoseof Primula minima. The big pink flowershad been replaced by capsules, butthe slope must have been spectacularwith them a month earlier.Still, for biodiversity, nothing beatslimestone. As it turned out, the largest166 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

array of alpine plants we saw grewwell below treeline, southwest of theHigh Tatras on a 4,000'-high plateaupeppered with sink-holes and icecaves. The Muranska Planina is part ofa large "protected landscape/' similarto our national forests, established in1977 and taking in about 5,000 squaremiles. It is administered by only tenemployees compared to 2,000 in theHigh Tatra National Park. This is thewildest part of the two republics, thelast place where wolves, bears, lynxes,and wild boars still roam. It wasempty of people. Once away from thefew farms and villages, we saw only acouple of woodcutters—indeed, topass down several of the lumberroads, we first had to unlock woodengates.We stayed in the rather impoverishedtown of Revuka, in a hotelwhich only two weeks earlier hadbeen sold by the State to private owners.We were their first guests. In fact,the hotel wasn't really open yet, andthey were still cleaning the wall-towallcarpets by scrubbing them withsoap and water in the parking lot.Needless to say, the carpets didn't fitvery well when they were nailed backdown. No matter, our hosts couldn'thave worked harder to make our staypleasant. After the first morning, theybought an espresso machine especiallyto satisfy the <strong>American</strong> demand forbreakfast coffee, and one evening agypsy musician accompanied ourhilarious attempts—under Frank'senthusiastic guidance—to dancepolkas and the csardas.Our daytime guide was Dr. PeterTuris, the young chief botanist for theMuranska, and right away he took usto where the main road (beautifullyasphalted) rises to cut through a limestoneformation. The white fringedpinks of Dianthus hungaricus splayedfrom the rock; a colony of Primulaauricula had seeded into the crevices.In a glade in the woods across theroad, near a stand of golden Trolliusaltissimus, another limestone outcroppingwas covered with moss in whichcolonies of the delicate, pale blue harebell,Campanula cochlearifolia, grewnext to Pinguicula vulgaris, a moisturelovermore often seen in bogs. Fartheralong the main road, where a hair-pinturn sliced through heavy clay banks,the gorgeous pink pincushions ofScabiosa lucida waved on foot-highstems next to compact clumps ofCampanula carpatica. The latter hadrather congested foliage and hugelavender saucers on short stems andlookedclose to the form called"turbinata."The next day, Frank inched the busup a precipitous lumber road andparked it in an open meadow fragrantwith thyme. From there, the able-bodiedwalked up a trail lined withPinguicula and Moneses uniflora, theround leaves of Soldanella hungarica(slightly larger than S. carpatica, whichwe'd seen growing in the acid Tatras)carpeting the adjacent deciduous forestfloor. After crossing a field studdedwith newly planted conifers, weducked under some larch branchesand crawled (at least I, with no headfor heights, did!) out to the edge of acliff. And there they were: 8"-highshrubs with narrow evergreen leavesand with every accessible seed headcovered with a little white bag. Dr.Turis is conducting research onDaphne arbuscula, trying to discoverwhy it is so rare in the wild. Thedaphne, as are many of the otheralpines growing on the Muranskabelow treeline, is a relict of the IceAge, but it is also an endemic andindeed, according to Dr. Turis, is fairlywell restricted to this particular cliff.Sometimes it is listed as coming fromHungary, but that in itself is a politicalOn the Track of Daphne arbuscula 167

elict dating to the end of the FirstWorld War, when Czechoslovakia wascreated in part from Hungarian territory.Now, of course, the daphne mustbe listed as Slovakian.Whatever its nationality, Daphnearbuscula is a marvelous rock gardenplant with clusters of tubular lavender-pinkflowers appearing in Mayand often again in the fall. It doesn'tseem to set seed in cultivation, but it iscertainly hardy at least into USDAZone 4 and is easy to grow. Limedoesn't appear to be a requisite.Certainly most of the bushes we sawwere rooted directly into the cliff, butsome also seemed to be growing in thelayer of humus overlying the limestone.This was acid enough to supportmountain cranberry, Vacciniumvitis-idaea, although lime-lovingPrimula auricula and Gentiana clusii, atrumpet gentian in the acaulis group,grew there as well. As the King ofSiam said in the musical comedy, "It'sa puzzlement."Curious to see what was going on inhis domain hundreds of feet below, Dr.Turis disappeared over the edge of thecliff while the rest of us ambled back tothe bus. Frank had borrowed cupsfrom the hotel and had rigged animmersion heater to make coffee, completewith fresh cream from the busrefrigerator. Sitting on the thyme, westrained particles of coffee beansthrough our teeth (in these parts,"Turkish" coffee is made by pouringhot water over regular grind) andpassed around Frank's pictures of hiswife and two children. Eventually, Dr.Turis came bounding up the trail toreport that soldanellas were stillblooming, in mid-July, in the gorge,where patches of snow and ice werestill melting. Somehow, I wasn't surprised.In this charmingly enigmaticpart of the world where revolutions arevelvet and even the Communists triedto preserve the land, why shouldn'tdown be as good as up, or alpine plantsgrow happily in the woods?Along with an acre of garden in Georgetown, Massachussetts, Joan Means shareswith her husband, Bob, an interest in searching for great plants in their natural settings.Joan reports that for the first time this spring Boykinia jamesii bloomed in hergarden. Nine cherry-red flowers appeared on a single flowering stem of the PikesPeak form, and Joan is thrilled!Drawing by Rebecca Day-Skowron168 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

CalochortusSensational Native <strong>American</strong> Tulipsby Claude A. BarrI n the western half of our continentdwells a brilliant and versatilerace of spring bulbs that are knownand enjoyed but little outside theirnatural area. Calochortus, comprisingthe mariposa tulips and related groupspopularly known as fairy lanterns orglobe tulips and cat's ears or startulips, are the instant delight and envyof every flower lover who sees them,whether as specimen groups in thegarden or in nature's lavish landscapes,where fifty thousands holdtheir shining cups stiffly erect to thesun and the breeze on a quarter-mileslope.The mariposas gain their devoteesthrough many lines of appeal. Thetypical form of the flower is of matchlessgrace. Three very broadly obovatepetals with recurved tips form anample bowl or a deeper chalice with abroad rim; three like-colored sepalsthat alternate between the bases of thepetals. Low upon the inside of eachpetal is a splotch of strikingly contrastinghue called the gland. It may be flator deeply pouched, is often surroundedby decorative tufts of bright hairs,and usually forms the axis of a fancifuland intricate pattern which the earlySpanish adventurers in Californiaaptly saw as the wing-eye of a mariposa—butterfly,in our tongue. This"eye," this scintillant peacock feathermotif, seems the reason for being ofthe flower's tri-part structure, peculiargrace and exquisite modeling.The rich effect is enhanced by textureand color in the ground of theoften bearded segments: pure, dazzling,fine-velvet white in Calochortuscatalinae, melting lilac in C. macrocarpus,pinks, grays, citrons, purples andreds in the C. venustus varieties,molten gold in C. clavatus, andorange-vermilion in C. kennedyi, sointense that the delicate pile of its velvetgives reflections of pale lavenderin certain lights. There are perhapshalf a hundred species and nearly asmany more varieties and color forms,all widely set apart in appearancefrom the forms and species of OldWorld tulips.Slight acquaintance does not compassthe wonder of these flowers. But,believing, one demands, "Why are notthese rare beauties in all our gardens?"Ah, there! Though more than a hundredyears have gone since DavidDouglas gathered the first of them for169

eager English experimenters andthough 50 years or more some ormany of the species have been on themarket, still they remain the playthingsof a few lucky or extremelyclever gardeners who somehow meettheir exacting requirements. Just whatthese are a steadily augmenting coterieof admirers is striving to know.The usual final failure under thebest available advice and care andtheir usual advent from California arethe basis of the familiar assumptionthat these most desirable of all nativesare not hardy. The generalization goesvery wide of the mark. Those whichhave their origin in California includetender kinds from the southern coastthat bear practically no frost to othersthat withstand fairly low temperatures,even light freezing during earlygrowth if the all-important factors ofsoil and moisture are right.In addition a few high-mountainsorts are quite hardy and—a fact notcommonly dwelt upon—some twentyspecies are native outside the mildcoast state or but touch its colored borders.While a few of these are Mexican,others, chiefly in the showy class andincluding some of the most outstandingand distinguished in form andbeauty, are to be met with from northeasternCalifornia far into the intermountaindry belt of British Columbiaand across Washington and Oregon,Idaho, Montana and Wyoming, twospecies extending onto the plains ofthe Dakotas and northwesternNebraska and following the coldranges of the <strong>Rock</strong>ies far to the south.In the difficult environment of mygarden on the South Dakota plains thesuperhardy species have proven theirtrue worth. Here a basically heavy soil,often a shortage of moisture in thegrowing time, occasional deep wettingin the dormant, and rapidly fluctuatingand extreme temperatures haveprovided a natural laboratory forobserving various limits of adaptability.Yet here has been met an encouragingsuccess in growing nearly all thekinds available commercially in recentyears and a number of rare ones sentme by friends.My first effort, with a mixed lot ofthe vaunted gaudy Californians, wasas fruitless as anyone may expect whoplants them wholly without understanding.There followed a splendidperformance by one of the local kinds,the lovely C. nuttallii, brought in froma gravelly ridge a mile or so from myhome. This gave new courage and preparedme for the next step, the possessionof Carl Purdy's wonderful catalog,which described species andforms in bewildering variety and gaveexplicit cultural directions.Bulbs for a good-sized plantingwere purchased and put into theground in October, the soil of the gardenbeing lightened by the addition ofsand and gravel to a depth of six inches.Taking on faith an impression as tohardiness, no protection was given.But as the good Deity looks after foolsand children, the winter was mild,with light snowfall, and frost did notstrike deeper than six inches. Springbrought no superabundance of wet,thus furthering the absorbing adventure,and a dozen kinds, Californiansand others, gave thrilling bloom. Therecord notes that two or three kindsdid not bloom at all, possibly from toolittle moisture, that C. plummerae andC. catalinae, too tender, had renouncedearthly cares, and that an occasionalbulb was missing from others.Calochortus catalinae and C. plummerae,procured a second time, have sinceperformed faithfully, year after year,given full protection from cold.So began an extensive series ofexperiments, testing many types ofsoil, varying the planting depth,170 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

improving subdrainage, increasing orlessening shade, seeking the rightmoisture for the growing period. Oneyear severe cold came. All theCalifornians had been given their thenaccustomedblanket of 12" of hay at thefirst serious onslaught of winter—all,that year, but a test lot of theredoubtable C. vestae, one of the finestof mariposas, perhaps the most adaptableof all, and one of the hardier of theCalifornians. The cold wave held for amonth. A drop to 40°F belowcame onenight, and the unprotected lots hadonly an inch or so of snow cover.Calochortus vestae failed utterly, and Inoted with surprise and shock, inApril, the vacant spot where my onlybulbs of the rare and costly "pinkshades" had been ventured. From that Iquite lost interest in cold tests, and so Ido not know, exactly, how much someof the Coast Range bulbs will bear.Circumstantially, side by side withC. vestae through that fatal trial stoodC. macrocarpus, C. lyallii, C. apiculatus,C. gunnisonii, C. nuttallii from southwesternColorado, and other cold-climatekinds, and 40°F below impressedthem not at all. They came through toa bulb.The following data are now clearlydetermined: outside the growing season,early March to mid-July, here, thesoil may be as dry as ground canbecome in this dustbowl climate, evenfor the Californians accustomed totheir winter rains; a dry dormant bulbis a safe one. There has been no opportunityin many years to observe theeffect of a continuously wet summerand fall, but occasional soaking rainsare not fatal when soil texture anddrainage provide quick dissipation ofthe excess. Planting may be done aslate before winter sets in as convenient.Four inches to the base of thebulb is a good depth; deeper plantingis of no advantage except for extralargebulbs. They grow well at twoand a half inches apart but make agood show spaced four inches. Bulbsthat have remained so dry that theyhave merely swelled their root nodesand made a start of tip growth byearly March bloom freely if theyreceive moisture at that time or assoon as the ground is frost free.Within the month shoots of themost precocious will appear, rednosedand hardy, but from the firstactivity of the tips beneath the soiluntil blossom buds are in evidence is atouchy time and moderate moisture isthe safe rule. For the less hardy kindsit is well to have lath frames, burlappads, perhaps hay, at hand until frostsare surely past. They want plenty ofwater from the appearance of the budsuntil just before flowering time; then,preferably drought. The new bulbwhich grows annually within the old,crowding the flower stalk into acurved position against the old husk,is fully developed at flowering timeand matures without further supply ofmoisture. At this time or with littledelay a thorough drying out servesperfect ripening. In a congenial environmentthe bulbs continue for manyyears.Just here a criticism of acceptedbeliefs is due. Alternate freezing andthawing during early growth is creditedwith being enemy number one ofCalochortus. Granted that repeatedfreezing is injurious, the careful observationsof years are 1) that frost injury,even killing back to the ground, maybe only an accessory act and that whenfatality occurs, a clinging, smotheringmoisture does the dirty work after thefreezing of a heavy, soggy wet soil;meanwhile calochortus bulbs areentirely immune in this same soil if onthe dry side. 2) That the semi-hardyones really do not differ in their essentialreaction, as I have had themCalochortus 171

esume growth after sudden cold—inthis garden a late March blizzard hasforced the mercury to zero—had takenthe first few inches of leaf, when thesoil warmed quickly and moisture wasnot excessive. And 3) that the bulbsperish in wet ground in an apparentlyidentical manner without Jack Frost'scoming on the scene.But ahead of suggestions for gardenhandling let us pause to look into theprivate lives of the mariposa bulbs. Inthe West's great open places, with afew exceptions, they forgather, worshippingan ardent sun, selecting theirparticular abodes with a knowing eyeto a sloping surface and a subsoil thatis fully capable of carrying downwardand away any unbearable surplus ofwater taken into the earth. More oftenthan not they grow in regions of low,irregular rainfall and active and dessicatingwinds. Further, the prairie soilswhich are acceptable to them, theadobe soils, or sandy deserts and sagebrushplains, and the stony mountainsideswhere a pick is required to extricatethe bulbs contain little humus,and this leanness also aids drying.With these habitat characters inmind the gardener will seek a moderatelylight medium such as will bereadily warmed by the sun and avoidrichness. A lean soil like the subsoilfrom an excavation or a cut bank willreturn to relative dryness while richsoils are still reeking wet. Some finenessof texture at least in contact withthe bulb seems their preference andconducive to good coats. Clay, acceptableto such as C. eurycarpus, C. nuttallii,C. vestae, C. venustus, C. purpurascensin their native climates for itsgreater storage capacity, in a wet climatemay become a clinging deaththrough that same property, that andits natural coldness that holds backgrowth when growth must be surgingupwards. Clay, leafmold, and humusincrease moisture capacity, do theynot? Avoid them, along with all thattends to defeat dryness. One must notfear to provide starvation rations, foran astonishingly little fat-of-the-landwill nourish a mariposa's beauty.A medium of the desired qualitiesmay be compounded of one-third veryfine clean sand, one-third fine limestonechips, and one-third lean loam.Alternates are coarser sand, any finescreenedgravel, any convenient earththat has not been enriched. It may benecessary to employ a portion of subsoil.If a heavy loam must be used themeasure may be reduced by half or tojust enough to fill in not too completelybetween any sand grains.In early planting, one speciesshowed unmistakable dissatisfactionwith drainage facilities or growingmedium or both. That most brilliant ofthem all, C. kennedyi, darling of thedesert gods of Ojai, the Panamints andDeath Valley, freely sacrificed herselfto demonstrate the family hatred ofstagnant wet. The least affected of theplants came blind, that is, withheldtheir blossoms; others suffered theusual sickening and withering of thefoliage, and the bulbs, still firm, werehastily rescued and dried; some, damptoo long, were full of a mushy decaywhen examined.Desperate, I vowed to build a suitabledesert for C. kennedyi. And little asI knew of real deserts, I happened todo the right thing. Well out in theopen a place was selected, away fromthe close air and fitful reflected heat ofwalls and with practically a full day ofsun. An excavation of 20" exposed anabsorbent shale which, it seemed,would take care of subdrainage.Twelve inches of coarse gravel weretamped in, an inch of fine gravel tosupport the soil layer, three inches ofsand with just a slight admixture ofloam. At this depth, four inches, the172 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

ulbs were placed, covered with thesamesoil, and the balance of the holefilled with almost pure sand. Abracadabra!And a winter of suspense—doubt—and condemnation.The greater wonder and excitement,then, as C. kennedyi came forth to greetthe spring in all her native queenlysplendor, and as thus, responsively,recurrently, she serves her foreignbondage.But as the treatment seemed undulyharsh, a similar planting was made,another year, with the difference of alittle more and "better" soil. Theresult? No drama here. The C. kennedyilives but has never flowered. And theleaf growth is narrower, more channeled,lacking most of the frosty bloomand white margin that mark luxuriantwell-being in this species.In the desert type of planting, whichdoubtless will aid in growing manymariposas where other efforts havefallen short, the gravel layer acting as acatch basin is not intended to remain areservoir; an outlet must be assured.Thus moisture depletion is permanentlyprovided for, and capillary moistureis cut off from below, a further vitaladvantage. The gravel may be shallowerif the escape is good. Somecoarser gravel may be added to therecommended sand-limestone chipleanloam mix, up to the level of thebase of the bulbs, augmentingdrainage and simulating a commonnatural footing. For most species a 4"rooting layer is preferred as manykinds are stronger growing.Means of surface drainage are theusual ones of raising the beds and tiltingthe surface. As in the wild, grassesand other vegetation compete with thetulips for available moisture. Shrubsthat form networks of shallow rootsmay be made use of where they willnot cast shade. Whether low annualsthat will survive without watering areto be used to dress the beds after thebulb season is a matter for consideration.Mulches or cover, as such, overthe dormant bulbs are best not usedexcept when the ground is dry or atfreezing temperature.Digging and storing the bulbs oversummer, sometimes effective wherethat season brings much rain, doubtlessmay be obviated by the adjustmentof soil and drainage. When summeringin the ground results in failure,predisposing factors have with certaintybeen at work prior to the dormanttime. Digging gives the groweropportunity to note the condition ofhis bulbs, and if they are anything lessthan perfect, he will do well to remodelhis program. On the other hand ifthe set-up has produced thrifty growthand good flowering, full-sized replacementbulbs and crisp and clean ripening,with fair probability they willsummer in the ground.An unhappy phase of Calochortusculture in the form of a disease alsoinvolves moisture. It is popularlycalled lily leaf rot, botrytis, or mildew.The critical period is just before flowering.If at that time cloudy, dampweather comes, infected plants willdarken and wither at the leaf tips, andas the trouble advances, buds droopand flower parts and portions of thestem may be destroyed. The blight issometimes detected at an earlier stagein distorted leaf tip growth, noted inlateral curling, browning and stunting.Hot sun and dry air halt the destructionat any stage. The infection is oftenpresent in wild stands of the plants,appearing with wet weather and havingno more final effect than to ruin acrop of blossoms. The bulbs are notdirectly destroyed. Scientific knowledge,as far as I can learn, is lacking,and at present no one can prescribe.The answer may lie in Clorox treatmentor in hormones. FortunatelyCalochortus 173

some species and certain strains ofothers seem immune. In my garden,Old World tulips grown in close proximityhave not contracted the trouble.Among very hardy kinds C. apiculatus,C. macrocarpus, C. greenei, C. gunnisonii,C. eurycarpus, and C. nitidus arebest ventures for the beginner, whileC. venustus var. purpurascens, C. venustusvar. citrinus, and C. vestae, of theCalifornians are very adaptable andfairly hardy. Mr. Purdy recommendsC. venustus var. citrinus, C. venustusoculatus, C. vestae, C. nitidus, C. eurycarpus,C. lyallii, and C. apiculatus as practicallyimmune to the leaf rot.The fairy lanterns and cat's eartulips are less exacting than the majorbranch, liking some shade and leafmold,and where the mariposas can beaccommodated, these groups will befound more uniformly hardy and amiable.Each variety has its own distinctcharacter, charming in degree, andwhen one has come to know them, tolook for the silken glow of the lanternsor to expect the half-mischievous andever watching "eyes" of some of thecat's ears, an absence would be notedsadly.If a prophecy may be entertained,the calochorti of the future are destinedto prolong the glory of springbulb bloom. They will follow closeupon the receding wave of the Darwintulips and surge on into July, andsurely we may look forward to the daywhen first one, and finally numbers,will be brought under the transforminginfluences of hybridization andselection and made amenable to generalgarden use. Now and again naturetakes a hand at adapting her offspringto meet new and different conditions,and in any lot of bulbs may appearone that survives and prospers whileits fellows perish. Such a marked individualis to be treasured as a pearl ofgreat price by the gardener whoseunderstanding eye detects it, and theutmost thought and effort given itspreservation and increase. This is theprimary commission to those whogrow Calochortus. For in strange climatesand in strange soils may newadaptive characters best be observedand tested, and doubtless there alsowill this aloof and many-starred racebe wholly fitted to stand alongsidepresent favorites.Claude Barr lived on a ranch in South Dakota. He was the pioneer horticulturistfor the Plains and <strong>Rock</strong>y Mountain regions, the original xeriscaper, and one ofthe greatest early voices of the <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong>. His Jewelsof the Plains is a classic of horticultural literature.This article was found (with the help of Prof. Ronald Weedon, Director of theChadron State College Herbarium) in the Claude Barr archives in Chadron,Nebraska. Written in 1939, it was accompanied by a folder containing a decade ofnotes and correspondence on growing Calochortus. The last entry in the folderwas a 1940 rejection by Flower and <strong>Garden</strong>. This was early in Barr's writingcareer, and it appears that Barr was devastated by the rebuff, and in any case, heput the manuscript and the folder aside forever.—Tom Stuart[Carl Purdy was a plant collector of note who sold many wild-dug bulbs ofCalochortus in the 1930s. He died in 1945. Current sources of Calochortusinclude Robinett Bulb Farm, PO Box 1306, Sebastopol, CA 95473. There is nowan <strong>American</strong> Calochortus <strong>Society</strong>. Write: ACS, 260 Alden Road, Hayward, CA94541. —Ed.]174 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

Harmony with Natureby Jaroslav Faiferlik^Everyone is part of Nature. Weall depend on her, our vital functions,including mental ones, yielding to herlaws. There is an instinct in us that letsus sense and emotionally live throughNature's various scenes and stages.We find an inner harmony and healingfor our souls in her.Country scenery has its genius loci,the spirit of each place, whichimpresses and excites our emotions—whether in a joyful, beautiful, sad, orunpleasant way. The impact of a particularlandscape depends on the sensibilitiesand mood of the individual.We look to Nature for ways to putourselves at ease again in the worldafter the hustle and bustle of humantrade and interaction. This could perhapsbe gained by arranging our gardensin a natural style. Havingdreamed of a desirable garden scene,we try to obtain the best flowers andnatural materials to in order to bring itin to being. Some plants, for example,require the company of rocks or pebbles,while others prefer decayingwood, and so on.If we really want to cooperate withNature, we should take advantage oflocal ecological conditions. Of course,we can change the final face of thelandscape—artificially—but wherethere is a desert, we often find ourselvesmodelless in ridding ourselvesof that bleak scenery, in completelyconverting it to something else. Andhow hard it would be not to plantriverine growth next to a rich supplyof water! True cooperation betweenNature and the gardener suggests thatwe refrain from inventing artificialvegetation inconsistent with the originalconditions of natural reality.By respecting the original compositionof the ground and choosing theright plants and other natural elements,the desired psychological effectmay be acheived. The larger the garden,the more variety we may grant it.An undulating landscape with clumpsof trees and shrubs offers us a greatchance to add a variety of habitats.Then each small area just waits for usto arrange it well and finally berewarded by a wonderful magic oflight and shadow.A garden's shady groves, for example,perfectly complement an inconspicuousfootpath. The path brings upmystery likely to strengthen anddevelop our interest and imagination.175

Beyond each visual obstacle appears asurprise hidden in the very next scene.Such a path may astonish us withgraceful changes caused by the progressionof Nature through the seasons.In such scenes we find the originalmodels of the paintings of the masters,including spring buds tensed withmaximum vitality as well as the tranquillityof winter rising through snowand hoarfrost. Thanks to the infinitevariability of weather, the continualshifting of day to night, and the alternatingbeauty of the seasons, theatmosphere of the landscape is at onemoment stimulating or at another subdued,always of interest, always new.Beauty and holiness call to us fromthe softly undulating grassy groundand from the proud semicircularcrowns of trees and shrubs. Connectedby the simple "S" pattern curve of atrodden footpath, a creek's meander,or the edge of a planting, the effect ofsuch a landscape is certainly deepened.A feeling of pleasant satisfactionis found in various green hues andlight-colored petals. Such harmoniousscenery moves our thoughts, mostpowerfully in the corners of a shadowed,mysterious garden. Wherethere are dark pines and overhangingwoody plants, one might even becomea bit nostalgic and sad.Let's create optimism then! Thesunny parts of the landscape plantedwith tiny and bright plants, as in realwildflower meadows, are the verybest places for that! Trembling tinyleaves, sparkling half shadows, thesoft movements in the rapids ofbrooks are joyful as well.Nobility is another emotion thatmay be evoked by natural scenes. Ifthere is, however, no view of mountains,of giant trees nor of powerfulrivers from our window, one of thequickest ways to evoke a feeling ofgrandeur is to plant large andstaturesque species, such as Miscanthus,Heracleum, Rheum, Polygonum.These may succeed in growing to anadmirable height in a short time.Flowers with large and colorful petalshave a similar effect.Dreary scenery where the developmentof plant life is limited troublesthe human mind. During hot summerdays our gardens may remind us ofsuch landscapes. Similarly, peoplemay find the dead remains of organismsugly and useless. But MotherNature values all of these as bearers ofpicturesque shades. Doesn't this pushus to borrow them from her and find aplace for them in our gardens?Strongly impressive scenery will beproduced in this way. Among thesegifts of Nature belong crumblingrocks, the dead trunks of trees, and soon. "The symbol of mortal life," onewould add. But actually we are goingto express the cycle of life in our gardens.As soon as first plant takes rootfrom an old stump, we realize thereare no cemeteries in Nature. Thedecaying tree just carries on withanother task—the one parents gothrough.Thoughts, born of Nature's spirit,have constantly led us to the gate ofoptimism. We should never forget thatthis is a mission of our gardens, too.Let's create our favorite scenery, nomatter what it actually consists of—rockery, grove, heath. Only we mustremember, it is not for cheap decorationthat we build, but rather to trulycharm, to stimulate sensitivity andhappiness by obeying and understandingNature's effects and laws.Jaroslav Faiferlik gardens in Plzen, in theCzech Republic, and strives to create hisgardens in harmony with Nature, to livethrough natural activities, and to makethe workings of Nature available also toother people.176 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

Blechnum penna-marina (p. 183) photos by Sue OlsenDryopteris erythrosora (pp. 182-183) Woodsia polystichoides (p. 183)177

Adiantum venustum (p. 182)Polystichum polyblepharum (p. 182) photos by Sue O sen178 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

Athyrium niponicum var. pictum (pp. 181-2)Athyrium otophorum (p. 183)

180 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

Pacific Treasuresfor the Temperate Fern <strong>Garden</strong>by Sue OlsenX he ferns of nature's wonderlandwere first cultivated for both ornamentaland medicinal purposes. Some arestill in use as herbal remedies today,especially in the Orient. However,ferns, with their monochromatic hues,are primarily used in the contemporarylandscape to give coherence togarden design. Victorian Britain enjoyedits fern craze, but for most of thiscentury the only selections availablefor the <strong>North</strong> <strong>American</strong> gardener /horticulturistwere our natives (whichwere regrettably mostly wild collected,and unfortunately in some cases stillare), and several of the select Britishcultivars and European species. It wasnot until relatively recently that theabundance of mostly evergreen materialnative to Pacific Rim countries hasbeen researched, imported and introduced.And what wonderful introductionsthey are. Colorful Dryopteris,creeping blechnums, and an evergreenmaidenhair are but a few of thedelights now available for cultivation.With today's increasing horticulturalexchange with China and more diversespores arriving from Japan and theHimalayas, the prospect for discoveringfuture treasures is very high.Not all of these imports are smallplants, however. In fact, there's not arock garden "cushion" in the crowd.But, as I've seen 3'-plus. Osmunda is inperfect scale in such places as the rockgarden at England's Sizergh Castle, Iguess it all depends on your site (andperspective)!Meanwhile, at least four prizeimports in the flowerless categoryhave made their way into mainstreamgarden design in the '90s. These oncerare plants are here presented,admired, and promoted for their beautyand adaptability. They are followedin the text by newcomers that cancompete for the gardener's attentionand, in time, for priority in the landscapestructure. Unless noted, all ofthe ferns described are hardy and suitablesubjects for at least Zones 6-9.Athyrium niponicum var. pictum isthe overall best-selling fern in <strong>North</strong>America today (photo, p. 179). I havebeen in gardens where (lamentably) itis the only fern in the plant community—thetoken fern of choice.Commonly known as the Japanesepainted fern, its deciduous foliage isindeed painted with gray, blue, andpink-to-burgundy tints in varying181

intensity. Normally, this exceptionallyhardy variety grows to 15-18" in thegarden; however I have been givenplants that vary widely from thisnorm—stately knockouts thatapproach 3'! There is some speculationthat genes of the lady fern, Athyriumfilix-femina, may be involved withthese giants; however, further researchis desperately needed before the variationscan be defined with scientificaccuracy. Meanwhile, it is a beautifulplant that serves well as a tidy groundcover under the burgundy foliage ofJapanese maples, or in the company ofany shade-loving foliar or floral blues.Over time it has been in the trade asAthyrium goeringianum var. pictum, andas Athryium iseanum var. pictum,—• neitherof which it is. Athyrium iseanum, adelicately lacy but untested species, isjust now becoming commerciallyavailable. Athyrium iseanum combineswell with A. niponicum var. pictum orwith typical plants of the species A.niponicum, which, while less flamboyant,are in themselves worthy plantsfor subtle color in the sylvan scene.Color, by definition, is part of theglamour of another cosmopolitanworkhorse, the autumn fern, Dryopteriserythrosora (photo, p. 177),although in reality the "autumn" colordisplay takes place in April! It is hardto believe that this fern was virtuallyunheard of in cultivation in the UnitedStates 25 years ago. It was the veryunavailability of this ornamental thatled me to venture into the wonders ofpropagating from spores...a subsequentlyaddictive activity! Autumnfern is a tall, broad evergreen that furnishesa colorful complement in a bedof epimediums. Both plants preferdappled, deciduous shade, althoughwhen established both performadmirably well in almost full sun. Alittle kindness by way of shade in themidday helps, however. Dryopteris erythrosoravar. prolifica is a smaller counterpart,again rosy and evergreen, butwith a more finely cut profile andpropagable bulbils along the frond'smidrib. It is openly elegant and distinquishedin effect.Polystichum polyblepharum, the tasselfern, is a lustrous, evergreen staple forany woodsy planting (photo, p. 178).At 18" the shiny foliage gives life andlight in shady somber or, for that matter,in the flower vase. It must not beallowed to dry out. It looks especiallynice with low-growing, rustic woodlandwildflowers...trilliums, hepaticas,violets, but nothing too boisterous.The fourth in the category of betterknownAsian ferns is Adiantum venustum,the Himalayan maidenhair(photo, p. 178). This evergreen gardenextrovert creeps about in partial shade,giving an airy elegance to anyplanting, without overwhelming itscompanions. The pale new growthsprouts surprisingly early in thespring and at 12" is a refreshing understorycarpet for heavyweight evergreens,especially rhododendrons, azaleas,and kalmias. Unfortunately, it ismost inconsistent as a spore crop, oneyear producing in quantity, and neverprogressing beyond the prothalliastage the next. Flooding a spore cultureoften resolves this problem byencouraging fertilization, but resultshave been erratic at best.The following species tend to be lessfamiliar than the above selections, butas they become increasingly available,they should indeed be future standardsfor fern collections or be used asembellishments in the mixed bed.Amongst the lower growing speciesthere are several species of Asplenium—A.incisum, A. sarelii, and A.tenuicaule, all of which are delicate andlacy. But unless you have better-manneredslugs than I do, all must be culti-182 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

vated with every precaution available.Woodsia polystichoides is a more reliablechoice in the dwarf category (photo, p.177). As the name implies, the frondshint of Polystichum in outline, butunlike Polystichum, the foliage is softand deciduous. I like it in a casual settingwith shiny ground covers such asCoptis, Vancouveria or Asarum. Be sureto note its location so that you don'taccidentally plant something on top ofit during dormancy—or am I the onlyone who does this?Another deciduous beauty isAdiantum pedatum 'Japonicum' (Adiantumjaponicum, in ed., photo, p. 180)Tissue-thin fans of sunset reds radiatefrom brittle stipes (stems) as the gardencomes to life in the spring. In timethe color fades to a more traditionalgreen, but the grace of the typicalmaidenhair silhouette remains belovedand unchanged. This surprisingly sturdyone-footer is an outstanding choicein soft shade at water's edge.Athyrium otophorum has been on themarket for just over a decade andbears uniquely colored fronds of limeand raspberry (photo, p. 179). This 2'species retains its foliage in frost-freewinters but can be more wisely handledas a deciduous specimen. Thesherbet shades associate harmoniouslywith dark greens and wine-reds.However, unless you're into screamingcombinations (say Houttuynia andvariegated ajuga), it should be wellremoved from anything even vaguelyblue or yellow.Phegopteris decursive-pinnata is myfinal suggestion in the deciduous category.This is a refined ground coverwith stiffly erect, apple-green 15"fronds. It is very hardy and adaptableand an excellent cover for maintaininga tidy appearance in neglected areas orto dress up the formal shade border. Itwill wither with the first frost soshould not be used as a focal point inthe winter view. While most fernsmust be propagated from spores, thisspecies can easily be divided once severalcrowns have formed—fall is thepreferred season.Two species of Blechnum add diversityto the garden design. NewZealand's Blechnum penna-marina is afairly well-known evergreen groundcover that once established will colonizein poor soil and sunshine (photo,p. 177). A sunny exposure is recommendedfor keeping the planting compactand tidy. New growth is a mixtureof holiday reds and greens, whichwill be maintained throughout the seasonin a sunny location. Blechnumniponicum, by contrast, grows as a singlerosette of sterile fronds with afountain of fertile fronds at its center.Like many species of Blechnum, thistoo has colorful new growth. Unlikemany species, however, this is quitecold tolerant. My own spores camefrom a good friend who rock gardensin Connecticut. Blechnums in generalwant a lime-free soil and resent potculture. This latter must be taken intoconsideration when propagating, orpotting for a show. Let them share rootspace with a fellow plant.Dryopteris bissetiana and Dryopterispurpurella, which may very well beconfused in the trade, are offered asalternatives to (or in addition to) D.erythrosora. They, too, are evergreen,have autumn colors in their newgrowth and are reputed to be evenhardier than D. erythrosora. They arebushy and like shuttlecocks in formand can perform the landscape dutiesof a small shrub. In their companyDryopteris decipiens makes an excellentforeground plant or edging species.The foliage has a satiny, metallic patinathat plays delightfully with varyingangles and degrees of light. At onefoot in height, it is a quiet evergreenpartner in the fern composition.Pacific Treasures for the Temperate Fern <strong>Garden</strong> 183

Mickel lists it as Zone 5 in his newbook.Another Dryopteris, D. championii,has survived cold winters with class.This Japanese evergreen saves its beautyfor maturity. As a youngster it couldbe any of several attractive species.However, in established plants the 2'-plus fronds unfurl with a dusting ofsilver and when fully expanded are arich, dark, velvet green. It is especiallyhandsome as a guardian of white andpastel primroses.Dryopteris polylepis, introduced to<strong>American</strong> horticulture by NARGS legendRoy Davidson, stands out in thespring garden by virtue of the crozier'sdense cloak of prominent nigrescentscales (photo, p. 180). These are inbold contrast to the warm green tonesof the fern's emerging foliage. Plant itunder your Acer shirasawanum'Aureum' (formerly A. japonicum),where the fern will anchor the color ofthe tree. In the Zone 8 Pacific<strong>North</strong>west Dryopteris wallichiana haslong been admired, yet it has beentotally unpredictable in cold winters,sometimes surviving Zone 6 weatherwhile at other times expiring in Zone 8termperatures. Although smaller, D.polylepis is clearly the better choice.Treat it with patience, however, as it isboth slow-growing and resentful oftransplanting.A trio of polystichums round outthis brief portfolio of fern delicaciesfrom Pacific populations. Polystichummakinoi, P. neolobatum, and P. rigens areall excellent evergreens for generalpurpose landscaping, specialty fernplantings, and green unity in the colorfulbed. All appear to be more cold tolerantand less moisture dependentthan the attractive P. polyblepharum,which they resemble in shape andgloss. They are rigid, toothy species ofmedium height that best display theirindividuality when planted in combinationwith each other. Or, try combiningthem with various textures andcolors of hostas for a visual feast.While this is but a sampling of thebounty of recent imports, hopefully itincludes a new fern or two for yourgarden. The introductions of the past25 years have indeed extended theoptions and increased enthusiasm inthe fern world, whether for the collector'sappetite, the beginner's woodlands,or the shady rock garden.Enjoy!!!!For the fern lover, horticulturallyadventurous, or the botanical enthusiast,a new non-profit organization, TheHardy Fern Foundation, is working toexpand these introductions by testingferns for hardiness and ornamentalvalue in the <strong>North</strong>west and at numeroussatellite gardens throughout theUSA. There should, in time, be onenear you. Members receive quarterlynewsletters with reports and observationson fern culture in <strong>North</strong> Americaand throughout the world, have accessto a spore exchange and are offeredplants as they become available. Youcan help this program and your ferngarden as well. For further informationsend a SASE to The Hardy FernFoundation, 12921 Ave. DuBois S.W.,Tacoma, WA 98498. Thanks and goodgrowing!!Sue Olsen has been growing ferns formany years in her garden in Bellevue,Washington. She has travelled toChina and England studying ferns andhas introduced many new species andforms through her specialty nurseryFoliage <strong>Garden</strong>s.184 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

South African JournalKarroo to the Drakensbergby Panayoti KelaidisiR.ecent years have seen a flood ofgermplasm from the Andes, Turkey,Central Asia and the Western UnitedStates into horticulture. <strong>Rock</strong> gardenjournals are filled with pictures ofexotic plants from these locales, andmore and more plants are showing upfrom these areas—mostly in pot cultureand plant sales. With a fewnotable exceptions, much of this materialappears to be more exacting, andcertainly more challenging to grow forlong periods of time in the garden thanmore familiar, traditional Europeanalpines.I remember reading an article, once,that spoke of plants that "paid rent"—which is to say plants that bloomed foran extraordinarily long period of time,or else plants that had such beautifulfoliage throughout the year that theyhardly needed to bloom. Viola cornutais an example of a plant that bloomsvirtually the entire growing season inmy climate at least, while Sempervivumcultivars in their infinite variety arethe classic example of foliage alpines.Year after year I discover that practicallyany African alpine I acquire fitsneatly into one or both of these categories.I began to notice that theAfrican alpines grew very quicklyfrom seed or cuttings, often bloomingthe first year. They seemed to beunparticular with regard to soil andculture; a large proportion of plantsfrom the southern part of Africaapparently approximate that holy grailof nurserymen—the Ever-BloomingPerennial.One of the first African plants I evergrew was Euryops acraeus, the epitomeof silver leaved shrubs. Assuming thatsuch shimmering foliage properlybelonged to a dryland plant, I placedthe Euryops on a rather dry scree,where it proceeded to grow—eventuallyattaining a foot in height andalmost two across. It smothered itselfyear after year with golden flowers.Marty Jones from 8000' at Vail,Colorado, asked to try a few cuttingsonce, and I blush as I remember myrather grudgingly agreeing to his havingone or two, thinking why send apoor African to certain doom? Ofcourse, this bona fide alpine from10,000' cliffs felt right at home in Vailwhere it grew more luxuriantly than itever did in Denver. This exemplifiesthe cultural versatility of SouthAfrican plants.185

Then there was Oxalis depressa,known for so long as O. inops. Thisspread its underground bulbils thoughmany square feet of rock gardenbefore I realized that even the harshestColorado winter wouldn't faze it. Theleaves don't appear until early June,but the cheerful, pink, cup-like bloomson 3" stems last for much of the earlysummer. Place it where it can spreadwith wild abandon, and enjoy. Somuch for the myth of tenderness inSouthern Hemisphere plants! Nowthat a host of bulbs and succulentherbs, including Anacampseros, fourspecies of Lithops and almost 50species of Aizoaceae, have comethrough Colorado winters unscathed,it is apparent that not just high alpineSouth African plants possess tremendousgenetic tolerance to cold. Onecannot make pat judgments based onthe much warmer isotherms of theSouthern Hemisphere.In the early 1980s I visited VancouverIsland in midsummer. A highlightof that trip was visiting AlbertDeMezey's remarkable garden on FoulBay Road in Victoria. A steep bankcarpeted with Echeveria spp. next tothe house alerted me to how mildVictoria can be in the winter. Peatbanks covered with the foliage ofPleione were a further sign. But theopen, sunny screes were dotted withinnumerable plants of Helichrysummarginatum—a simply stunning midsummerbloomer. (This has been confusedwith the woolly leaved H. milfordiaewith crimson buds that bloomsmuch earlier in the season, but the realH. marginatum is a deep blue-green,leathery-leaved plant with a silverstripe on the margins of leaves bornein lax rosettes; the 2"-wide, whitestrawflowers are displayed on stems 4-8" tall. I have subsequently obtainedthis plant from several sources andfind that it does much better in a peatbed with some shade in Colorado.)Only a few helichrysums are beinggrown in rock gardens, but like somany plants from the Drakensbergthey bloom in our gardens from Julyonward, making them invaluable forextending bloom in rock gardens.African plants are fulfilling the dreamof year around gardening.Many more helichrysums havejoined H. marginatum to enliven thesummer doldrums with pink, whiteand yellow. A myriad of other SouthAfrican daisies—white, purple, andlavender Osteospermum, yellow Gazania,and black-and-white Hirpicium, toname a few—will often bloom forthree months on end. Three species ofDiascia have thus far proved to behardy, and suddenly there are availablemore and more species ofKniphofia and Crocosmia, and the firsthardy Moraea.The plant that most quickened ourenthusiasm, however, was the mysteriousice plant that had made the circlesof rock gardeners for years labelledsimply "Othonna sp. Basutoland," or"Mesembryanthemum sp. Basutoland." Iremember accepting three such plantsfrom Bob Putnam in the spring of 1980with considerable trepidation—surelyno ice plant would grow in Colorado.Like so many people who first grewthis plant, I was astonished as Iwatched it spread with such gusto thatfirst summer. I took a few cuttings inthe autumn, since surely anything solush, so green, so vigorous couldn'tpossibly be hardy. When it turned thatremarkable ruby-purple color in thewinter, I hardly knew what to make ofthe plant! But when it cleverly turnedback to Irish green with the first warmdays the next spring, I was completelycharmed by this chameleon of a plant.Each spring since I think I fully recapturethe shock and delight I first experiencedwhen for a few weeks this ice186 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

plant completely covers its muchbranchedstems with such cheerful,inch-wide, shimmering, daisy-like yellowblooms. And to think, at first Ididn't even have a clue to what it was.You can imagine how pleased I waswhen I found out that Bruce Bayer, theleading authority on plants of theSouth African karroo was to come toDenver and give a lecture. People inthe know assured me that no oneknew South African succulents betterthan Bruce. I grew impatient as thiswise scholar lingered over every bit ofvegetation the quarter mile or so ittakes to get down to the <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong>from the entrance gate. Upon arrivingat our specimen, Bruce proclaimed "ADelosperma, of course," and I heaved asigh of relief—it would be no problemto determine a species once we'd gottenit down to genus. "Don't be sosure," he went on, "The genus has severalhundred names, and it's neverbeen properly monographed, and I, forone, have never seen anything like thisspecimen in the karroo."Although I have subsequentlyinvestigated major <strong>American</strong> herbariatrying to find out more aboutDelosperma in general and this speciesin particular, I have never seen a specimenof Delosperma nubigenum taken inthe wild. And almost 15 years later, Iwas stunned to find no specimens ofthis species or its close allies in theCompton Herbarium at Kirstenboschin Cape Town. John Wurdack, of theUS National Herbarium in Washington,DC, took the initiative to writeleading workers on the family Mesembryanthaceae,and I will never forgetreceiving from him copies of the correspondence—threedifferent scholarshad given him three different names!Delosperma nubigenum seemed to fitour plant the best. What does thisplant look like in the wild? Since noone has ever seen a capsule on the cultivatedclone, is it self sterile? Howdoes it compare with wild germplasm?These are some of the questions thatnagged at me for years and spurredme on in the desire to visit the highmountains to seek out this remarkablemysterious mesemb.Johannesburg may be the principaladministrative capital of South Africa,but Cape Town will always be thepoint of departure for the botanicallyinclined. Not only is Kirstenbosch oneof the most exquisite public gardens inthe world, but the fynbos floristicregion, where Cape Town is situated,is generally acknowledged by botaniststo be the richest floral domain onearth in terms of plant speciation, relativeto its total area. From a distance,in midsummer the mountains of theCape look rather barren, but fromclose-up I had to agree with KuusRoux, an African botanist who felt thatfynbos with its proteas, plumy restios,and a welter of shrubby, bulbous, andsucculent plants really does resemble adusty Victorian parlor when viewed atclose range. Species density approachesthe equatorial rainforests in numberand variety. Even though I arrived inearly January, after the summer solstice,I was amazed to find ericas,restios, proteas, and numerous bulbsstill in full bloom every time I visited apatch of fynbos. It was only towardthe end of my trip that I realized thatthe high mountains both north andeast of Cape Town rise to sufficientheights that a great range of fynbosplants might well prove hardy one dayin Colorado: after all, we grow a goodmany alpines from the hills surroundingthe Mediterranean Sea from a latitudewith climatic parameters closelyapproximating the higher parts of theCedarberg and the Swartberg. If thisprove true, bar the door, Katy; our gardenswill never be the same.South African Journal 187

Careening through the KarrooMy first destination for a field triplay but a hundred and fifty miles fromCape Town, beyond the first fewranges in the heart of the karroo.Karroo is a term used in South Africato characterize the drier interior portionsof the country. Karroo generallyhas richer soil substrates than thenutrient-poor quartzitic sands onefinds in fynbos. Karroo is nearly asspecies rich as fynbos—and might becompared to the desert/steppe vegetationof central Anatolia or the Iberianpeninsula contrasted to the macchieone finds in these same regions, or thekarroo-like Great Basin desert orMojave contrasted with coastalCalifornia chaparral.I had managed to grow quite anumber of plants from the karroo andwanted particularly to investigate theescarpment of the Roggeveld mountainsnear Sutherland in the heart ofthe Great Karroo, an area renowned inSouth Africa for its harsh winter climate.I was fortunate to be accompaniedby Fiona Powrie, Kirstenboschhorticulturist specializing in Pelargonium,who has explored extensivelyin the mountains of South Africa andhas a tremendous grasp of the nativevegetation—both as a botanist andhorticulturist. There is a stark contrastbetween the coastal mountains, withtheir magnificent protea forests, andthe lowland karroo, reminiscent attimes of madronos on the <strong>American</strong>Pacific coast, and then again of olivegroves in Greece—until one notices thegigantic flowers! But soon we descendedto an even sparser scene, with tansoils and even more burned up vegetation,a setting that obviously had notseen rain in many months. When wefinally stopped to look around, thevariety and density of plants growingon the karroo astonished me: giantTylocodon shrubs with muscular trunksand an almost solid ground cover ofherbaceous plants like pelargoniums,dried stalks of who knows how manykinds of bulbs, and tiny crassulas,mesembryanthemums and other succulentsintertwined. Time and again Iwas struck by this dichotomy—aseemingly barren vista transforming toincredibly rich vegetation on closeinspection.Of course, large stretches of the karroohave been terribly overgrazed,reducing species diversity drastically.It is inevitable that agriculture willprosper on these rich soils, and largestretches of karroo vegetation nearWorcester have been turned into tablegrape plantations to satisfy Europe inthe winter and spring. Saddest of allwere the acres that had been plowedand planted to an exogenous Atriplex,which must be thought to producefodder more efficiently than the nativevegetation. Even so, there is still quitea bit of karroo left to enjoy—and Ibelieve that the floral bounty in thisregion has barely been touched byrock gardeners.Our base camp in the karroo wasthe town of Sutherland—renowned inSouth Africa for its cold winter weather.The vegetation in the town was virtuallyidentical to what one might findin the lower Rio Grande Valley—thelittle town of Truth-or-Consequences,for instance. I am quite sure that therainfall and temperature patterns arevery close to some of the mountainsaround El Paso or Roswell. And, ofcourse, plants from these parts of theUnited States are proving to be quitehardy, so when I saw giant Agaveamericana in Sutherland, or Eucalyptusin valleys not far away, I didn't loseheart altogether. Even colder weathermust occur in the escarpments 1000' ormore above the town.The landscape felt utterly familiar—188 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3

from a distance the mesas and landforms could have been Utah or northernArizona. The soils are mostlyderived from shales and are apparentlycircumneutral or even acid, which surprisedme. Unlike Western America,there seems to be relatively little calciumin the rocks of the karroo. Bothlandscapes are dominated by gnarled,dwarf shrubs—almost entirelyArtemisia and Atriplex in the dry West,but in Africa the variety of shrubs wasbewildering. Mostly Compositae, theywere almost all beautiful ornamentals:dark-green-leaved Pteronia with largeyellow flowers; Eriocephalus in a numberof species, all with small whiteflowers transforming into woolly seedheads;many species of Euryops—somewith waxy, succulent leaves, otherswith tiny, raspy leaves. At many stops,we saw neat mounds of Osteospermumcuneatum with habit and dusty grayleaves resembling Atriplex cuneatasomewhat, only with 3" cream and yellowflowers. There are also unexpectedfamilies, such as gnarled shrubs in theCampanulaceae called Lightfootia,which had tiny stars, sometimes yellow,sometimes pale lavender. Therewere frequent groves of dwarf, desertpersimmon in a number of species,forming dense colonies. Unlike theWest where the same two or threeshrubs can dominate for thousands ofsquare miles, the species compositionchanged at every stop, and new generaand even families kept cropping up.And the ground layer is a rock gardenersdream! There are a few familiargenera—Dianthus, for instance. Atevery stop there were pinks rathersimilar to the European species wealready grow. At one place nearFraserburg I found a cushion with atrunk of a root that would be the envyof any bonsai enthusiast—at least aninch and a half across: decades old forcertain. A few species of familiar generaof mints, Stachys forming billowingsilvery mats among rocks on manycliffs with large pink flowers and apowerful smell that justified the commonname "Dead man's mint," a wonderful,tiny gray Ballota africana withmuch larger flowers than its Europeancousins. There were dried remains ofbulbs everywhere, Albuca, Galaxia,Homeria, Lapeirousia, Moraea, Ornithogalumand who knows what else.There was even an Allium that musthave been native along one stretch oflonely highway.Of course, there were succulentseverywhere—primarily mesembryanthemumbut also large cushions ofDrosanthemum from deep pink towhite; spiny Eberlanzia looking likesome Mediterranean Sarcopoterium onsteroids; Malephora and Ruschia andDelosperma in many species thatseemed to vary significantly from onehilltop to another; and smaller clumpsof annuals—true Mesembryanthemumand the famous local Pherolobus. Wefinally even found Aloinopsis, one ofthe true specialties of the colder, centralkarroo. This was the only pinkone, A. spathulata, which by midsummerhad retreated into the dusty clay,leaving only a few leaf tips visible.It was surprising to find plants thatI associate with gaudy annuals, suchas Nemesia, forming dense and veryperennial mounds several places alongthe Roggeveld. At least three kinds ofthese have germinated well and comeinto full bloom less than a half yearfrom the time I first saw them. Itremains to be seen how perennial theyprove in Colorado—but even as annualsthey are attractive.I had seen pictures of Selago in variouspicture books on South Africanplants, so I immediately recognizedthe first of these I saw in the wild.Imagine a veronica with billowy, puffyflowers as if it had studied postureSouth African Journal 189

from a baby's breath. Sometimes thestarry flowers are pink, and oftenwhite, but most often they are a varietyof lavender shades or even a rangeof blues from powder and lavender tocobalt blue.For rock gardeners the genusAptosimum, commonly called karrooviolets in Africa, will undoubtedlybecome a major new pinnacle to conquer.There are several dozen speciesof Aptosimum, one occurring on practicallyany roadside in the karroo. Thesemay be tiny tuffets, like A. procumbensstudded with bright blue flowers(photo, p. 197). Imagine a lax rosetteof a compact, glossy-leaved penstemonsuch as P. humilis. Now imaginethat flowers are stemless, an inch ormore across in thick clusters of trueblue. I doubt that I will ever forget athunderstorm that punctuated thedrive between Sutherland andFraserburg early this year. As we triedto speed as quickly as possible overthe slick tarmac, I noticed darkmounds along the road. Stop the car! Itlooked as if some jokester had plantedinnumerable giant cushions ofVitaliana primuliflora ssp. canescens randomlyacross the desert pavementamong prickly mounds of Eberlanzia—an acanthamnoid succulent with powderygray leaves and pink flowers. TheVitaliana look-alike turned out to bemuch stiffer to the touch—almostspiny. Eventually we determined thatthis was either Aptosimum spinescens(photo, p. 197) or something quiteclose to it. We were to see this againand again throughout the Roggeveld,but never as densely pulvinate as atour first stop. The cushions were studdedwith hard, round seed capsulesthat were almost—but not yet—ripe.Finally we found a fresh bloom—identicalto Aptosimum procumbens andpure blue. A mound in full bloomwould be quite a picture—and adelightful plant pun to put alongVitaliana.Of course, it is more than a littlepresumptuous to write about the karrooon the basis of a week's travel inthe middle of the summer heat there.So varied is the flora in this extraordinarilyrich, vast region that the localbotanists find it necessary to specialize,and few pretend to know the floracomprehensively. From a few dozenstrolls and hikes over the period of aweek I know I saw more fascinatingand attractive mats, cushions andtuffets than I have seen in months inthe <strong>North</strong>ern Hemisphere.My final day spent exploring in thekarroo was on top of a broad tablemountain just north of Calvinia calledHam Tarn Mountain—Hamtamberg inAfrikaans. It is privately owned byranchers who are sensitive to overgrazing,and the flora appeared to bequite pristine on top. The tablelandwas perhaps 15 miles across with 1000'cliffs all the way around. We weregiven keys to go through several stockgates, and we wound up a narrowpath to the top, where broad slabs ofnaked stone were exposed on much ofthe surface. A dizzying assortment ofshrubs and herbaceous plants grewacross the top—which was considerablycooler than the dry desert below.There were Nemesia still blooming, andmany of the dozen or so species ofHelichrysum were at the peak of bloom.All of a sudden we began to seegiant, symmetrical mounds with avery alpine look to them. They were ofa densely pulvinate Ruschia, one of thelargest genera of mesembs. You couldprobably walk upon it and not makeany dents in the cushion. Only a fewpink flowers persisted on a few individualspecimens, but the plants weresimply stunning in their vegetativestate—studded with hundreds of deep190 <strong>Bulletin</strong> of the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Rock</strong> <strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Society</strong> Vol. 52:3