the economic valuation of the proposed ... - Nature Uganda

the economic valuation of the proposed ... - Nature Uganda

the economic valuation of the proposed ... - Nature Uganda

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

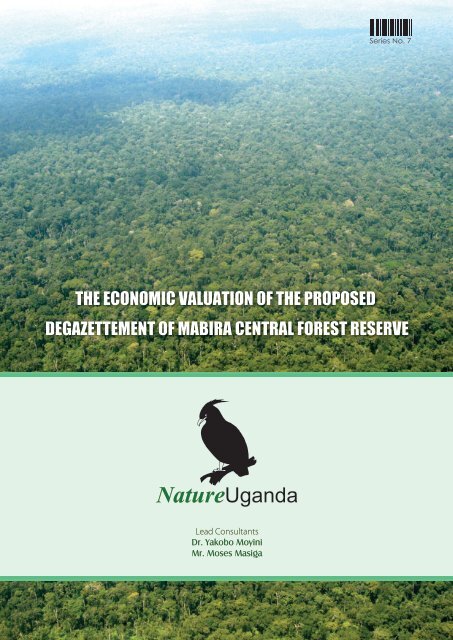

THE ECONOMIC VALUATION OF THE PROPOSED<br />

DEGAZETTEMENT OF MABIRA CENTRAL FOREST RESERVE<br />

<strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong><br />

Lead Consultants<br />

Dr. Yakobo Moyini<br />

Mr. Moses Masiga<br />

Series No. 7

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve<br />

With support from

THE ECONOMIC VALUATION OF THE<br />

PROPOSED DEGAZETTEMENT OF MABIRA<br />

CENTRAL FOREST RESERVE<br />

Reproduction <strong>of</strong> this publication for educational or o<strong>the</strong>r non commercial<br />

purposes is authorized only with fur<strong>the</strong>r written permission from <strong>the</strong> copyright<br />

holder provided <strong>the</strong> source is fully acknowledged. Production <strong>of</strong> this publication<br />

for resale or o<strong>the</strong>r commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written<br />

notice <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> copyright holder.<br />

Citation: <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> (2011). The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed<br />

Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve. <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> Kampala<br />

Copyright<br />

©<strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> – The East Africa Natural History Society<br />

P.O.Box 27034,<br />

Kampala <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

Plot 83 Tufnel Drive<br />

Kamwokya.<br />

Email nature@natureuganda.org<br />

Website: www.natureuganda.org

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

This consultancy builds on <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> earlier studies to identify important biodiversity areas in <strong>Uganda</strong> or key<br />

biodiversity areas. Thirty three (33) Important Bird Areas were identified including Mabira Forest Reserve.<br />

In this study, we make a case that policy formulation about natural resources needs to be informed with facts in <strong>the</strong><br />

present and full knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> future or predicted long term consequences. We are grateful to BirdLife<br />

International Partnership particularly Royal Society for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> Birds (RSPB) whose initial support enabled<br />

<strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> to undertake this study on <strong>the</strong> <strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> a section <strong>of</strong> Mabira Forest Reserve that was<br />

<strong>proposed</strong> for Degazzettement.<br />

The research work falls under our advocacy programme supported by various partners including BirdLife International<br />

through Jansen’s Foundation programme on ‘turning policy advantages into conservation gains’. It is our sincere<br />

hope that this report will trigger and sustain informed debate on conservation value <strong>of</strong> natural resources<br />

particularly critical ecosystems such as Mabira Forest Reserve. <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> recognised <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> an<br />

<strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reseve at a time when <strong>the</strong>re was a debate pitting conservation <strong>of</strong><br />

natural resources against intensive use for agriculture and industry and this report will contribute useful information<br />

to <strong>the</strong> debate not only for Mabira Forest but for o<strong>the</strong>r natural resources in <strong>the</strong> country. We acknowledge <strong>the</strong> support<br />

received from <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> secretariat especially <strong>the</strong> Executive Director Mr. Achilles Byaruhanga for coordinating<br />

<strong>the</strong> study and providing <strong>the</strong> consultants with all logistical requirements.<br />

We acknowledge contribution <strong>of</strong> Mr Telly Eugene Muramira who technically edited <strong>the</strong> report and Dr. Patrick Birungi<br />

<strong>of</strong> Makerere University for reading <strong>the</strong> earlier drafts as well as Dr. Panta Kasoma and Roger Skeen who pro<strong>of</strong> read <strong>the</strong><br />

report.<br />

Special tribute is paid to Dr. Yakobo Moyini (R.I.P) who was <strong>the</strong> lead consultant on this study that was conducted in<br />

2008. O<strong>the</strong>r persons who contributed to this report include Mr. Moses Masiga and Dr. Paul Segawa.<br />

We fur<strong>the</strong>r acknowledge EU support through <strong>the</strong> Important Bird Areas (IBA) monitoring project for providing <strong>the</strong><br />

funds towards printing <strong>of</strong> this report in 2011.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

V

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS<br />

SCOUL Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited<br />

VAT Value Added Tax<br />

PAYE Pay as You Earn<br />

CFR Central Forest Reserve<br />

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change<br />

NGO Non-Governmental Organisation<br />

CHOGM Commonwealth Heads <strong>of</strong> Government Meeting<br />

PFE Permanent Forest Estate<br />

CFR Central Forest Reserve<br />

CITES Convention on International Trade <strong>of</strong> Flora and Fauna<br />

TEV Total Economic Value<br />

NTFP Non-Timber Forest Product<br />

TCM Travel Cost Method<br />

CVM Contingent Valuation Method<br />

PV Present Value<br />

NFA National Forestry Authority<br />

FGD Focus Group Discussion<br />

RIL Reduced Impact Logging<br />

MPA Management Plan Area<br />

FD Forest Department<br />

PA Protected Area<br />

THF Tropical High Forest<br />

WTP Willingness To Pay<br />

GEF Global Environment Facility<br />

Vi The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

The Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> received and tabled for discussion a proposal to degazette and change <strong>the</strong> land use <strong>of</strong><br />

part <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve to sugar cane production. The proposal proved very contentious and resulted<br />

in civil unrest and a raging debate on <strong>the</strong> merits and demerits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>proposed</strong> land use change. Those in favour <strong>of</strong><br />

degazettement cited <strong>the</strong> numerous direct, indirect and multiplier <strong>economic</strong> impacts or benefits <strong>the</strong> change in land<br />

use will bring to <strong>Uganda</strong>. Those for conservation, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, cited <strong>the</strong> need to preserve <strong>the</strong> rich biodiversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest, and <strong>the</strong> need to respect both regional and international agreements on <strong>the</strong> conservation <strong>of</strong> forests and<br />

<strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>the</strong>rein. They also cited <strong>the</strong> public trust doctrine that charges government to manage and maintain<br />

forestry resources on behalf <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> citizens <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>.<br />

Whereas those in favour <strong>of</strong> degazettement have been quite eloquent in enumerating <strong>the</strong> <strong>economic</strong> benefits <strong>of</strong><br />

sugarcane growing, <strong>the</strong> pro-conservation groups have largely focused on <strong>the</strong> physical side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> argument and<br />

presented little <strong>economic</strong> data to support <strong>the</strong>ir arguments. The purpose <strong>of</strong> this study was to assess and compare <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>economic</strong> implications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two competing land use options.<br />

To undertake <strong>the</strong> assessment, a Total Economic Value (TEV) framework was applied. This was in view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact that<br />

forests are complex ecosystems that generate a range <strong>of</strong> goods and services. The TEV framework is able to account<br />

for both use and non-use values <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest and elaborate <strong>the</strong>m into direct and indirect use values, option, bequest<br />

and existence values.<br />

Lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge and awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> goods and services provided by forests previously<br />

obscured <strong>the</strong> ecological and social impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conversion <strong>of</strong> forests into o<strong>the</strong>r land uses. The TEV framework helps<br />

us to understand <strong>the</strong> extent to which those who benefit from <strong>the</strong> forest or its conversion also bear <strong>the</strong> associated<br />

management costs or opportunities foregone.<br />

In undertaking this study, <strong>the</strong> biophysical attributes <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR in general and <strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> impact in particular were<br />

reviewed. The most current and relevant inventory data available for <strong>the</strong> production zone <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR was used.<br />

The <strong>economic</strong>s <strong>of</strong> sugarcane production in <strong>Uganda</strong> and globally was also reviewed. Additional data and information<br />

were derived from an extensive survey <strong>of</strong> available literature. All this background data and information were <strong>the</strong>n<br />

used to derive <strong>the</strong> total <strong>economic</strong> value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> impact area within Mabira CFR and compare it with <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

<strong>economic</strong> yield <strong>of</strong> growing sugarcane.<br />

The analysis concluded that <strong>the</strong> benefits <strong>of</strong> conserving Mabira CFR far exceeded those <strong>of</strong> sugarcane growing. The<br />

respective total <strong>economic</strong> value <strong>of</strong> conservation was estimated at US$ 45.1 compared to US$ 29.9 million which<br />

was <strong>the</strong> net present value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> annual benefits from sugar cane growing. The study <strong>the</strong>refore concluded that<br />

maintaining Mabira Central Forest Reserve under its current land use constituted a better option than sugarcane<br />

growing. This was <strong>the</strong> case when <strong>the</strong> total <strong>economic</strong> value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest was considered, but also when just timber<br />

values alone were counted. The study noted however, that <strong>the</strong> degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR could still be favoured<br />

for o<strong>the</strong>r reasons o<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>economic</strong> considerations. The study recommended that should such a situation arise,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> developer (who is SCOUL) must undertake to compensate <strong>the</strong> National Forestry Authority for <strong>the</strong> total<br />

<strong>economic</strong> value (TEV) lost due to <strong>the</strong> change <strong>of</strong> land use. This requirement for compensation is legally provided<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

Vii

for in <strong>the</strong> National Forestry and Tree Planting Act, <strong>the</strong> National Environment Act and provisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> multilateral<br />

environmental agreements, especially <strong>the</strong> Convention on Biological Diversity. The compensation would also<br />

conform to <strong>the</strong> social and environmental safeguard policies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> and its development<br />

partners, including <strong>the</strong> need to conduct a thorough environmental impact assessment (EIA). The appropriate level <strong>of</strong><br />

compensation <strong>the</strong> developer will be required to pay is US$45.1 million, payable to <strong>the</strong> NFA to support conservation<br />

activities in <strong>the</strong> remaining part <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR and o<strong>the</strong>r reserves.<br />

The study also noted that Government could also waive <strong>the</strong> requirement for compensation. The study however,<br />

noted that such an action would tantamount to provision <strong>of</strong> a subsidy to SCOUL amounting to US$45.1 million or <strong>the</strong><br />

total <strong>economic</strong> value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lost value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest due to <strong>the</strong> <strong>proposed</strong> change in land use. The waiver would also<br />

tantamount to a gross policy failure, particularly in view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> efficiency questions surrounding SCOUL.<br />

The study also noted that if <strong>the</strong> developer paid <strong>the</strong> US$45.1 million compensation, <strong>the</strong>y would in effect be purchasing<br />

7,186 ha <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR at a fairly high cost per hectare. Land in <strong>the</strong> vicinity currently goes for UShs 500,000 to 1,000,000<br />

per acre (or Ushs 1,250,000 –2,500,000 per hectare). If SCOUL were to pay UShs 2,500,000 per hectare, double <strong>the</strong><br />

upper range, <strong>the</strong> company would purchase 30,668 ha <strong>of</strong> land. For <strong>the</strong> equivalent <strong>of</strong> 7,186 ha, if SCOUL purchased <strong>the</strong><br />

land from private sources <strong>the</strong> company would pay UShs.17,965 million (or US$10.6 million), an amount less than <strong>the</strong><br />

compensation figure calculated in <strong>the</strong> study.<br />

The study finally noted that in addition to <strong>the</strong> financial and <strong>economic</strong> questions presented above, o<strong>the</strong>r equally valid<br />

issues needed fur<strong>the</strong>r investigation. They include <strong>the</strong> need for compensation at ‘fair and equal’ value, <strong>the</strong> current<br />

implied objective <strong>of</strong> national self-sufficiency in sugar production; and land acquisition options available to <strong>the</strong><br />

developer.<br />

Viii The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Acknowledgements iv<br />

Acronyms and Abbreviations v<br />

Executive Summary vi<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents vii<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Figures viii<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Tables ix<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Boxes x<br />

1.0. INTRODUCTION 1<br />

1.1. BACKGROUND 1<br />

1.2. THE Degazettement PROPOSAL 3<br />

1.3 SCOPE OF THE ASSIGNMENT 5<br />

1.4. METHODOLOGY 6<br />

2.0. BIOPHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF MABIRA CFR 7<br />

2.1. SIZE AND LOCATION 7<br />

2.2. GEOLOGY AND SOILS 7<br />

2.3. PLANTS 8<br />

2.4. BIRDS 8<br />

2.5. MAMMALS 10<br />

2.6. AMPHIBIANS 10<br />

2.7. REPTILES 10<br />

2.8. BUTTERFLIES 10<br />

3.0. ECONOMIC EVALUATION OF THE SUGAR SECTOR IN UGANDA 13<br />

3.1. Global Sugar Production Trends 13<br />

3.2 History <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sugar Industry in <strong>Uganda</strong> 14<br />

3.3 Sugar Production and Consumption Trends in <strong>Uganda</strong> 17<br />

3.4. Performance <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>’s Sugar Sector 16<br />

4.0. EVALUATION OF DECISION TO CONVERT MABIRA CFR FOR SUGARCANE<br />

PRODUCTION 18<br />

4.1 Sugar Production Model for <strong>Uganda</strong> 18<br />

4.2. The Value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sugar Sector in <strong>Uganda</strong> 20<br />

4.2.1 Value <strong>of</strong> Reproducible Tangible Assets ( sugarcane) 20<br />

4.2.2 Value <strong>of</strong> non-reproducible assets <strong>of</strong> sugar factory (Land at <strong>the</strong> Company owned nucleus<br />

sugarcane estate) 21<br />

4.3. Cost <strong>of</strong> Production and <strong>the</strong> Determinants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Competitiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sugar Sector in <strong>Uganda</strong> 22<br />

4.4. Options for Improving <strong>the</strong> Competitiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sugar Coorporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited (SCOUL) 25<br />

4.5. CONCLUSIONS 29<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

ix

5.0. THE CONSERVATION OPTION 31<br />

5.1. CONSERVATION OPTIONS FOR MANAGING FOREST RESOURCES 31<br />

5.2. CONSERVATION ECONOMICS 31<br />

5.2.1 Importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>economic</strong> <strong>valuation</strong> 31<br />

5.2.2 The Total Economic Value 32<br />

5.2.3 Analytical framework 35<br />

5.3. VALUATION 37<br />

6.0. DISCUSSIONS AND CONCLUSION 47<br />

6.1. DISCUSSIONS 47<br />

6.2. CONCLUSION 49<br />

x The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

REFERENCES 50<br />

Annexes 59<br />

Annex 1 Biodiversity Report 59<br />

Annex 2 Inventory Data 79<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Figures<br />

Figure 1 Map <strong>of</strong> Mabira and <strong>the</strong> Proposed Area for Degazettement 4<br />

Figure 2: Cost-benefit analysis <strong>of</strong> an alternate project, to continued conservation 6<br />

Figure 3: Centralised and contract farming model in sugar companies in <strong>Uganda</strong> 18<br />

Figure 4: Value chain for sugar cane to sugar 27<br />

Figure 5: Framework <strong>of</strong> specialisation for sugar industries 23<br />

Figure 6: The Total Economic Value <strong>of</strong> Forests 33<br />

Figure 7: Graphic Illustration <strong>of</strong> Willingness to Pay 37<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Tables<br />

Table 1: Mabira CFR Area Proposed for Degazettement 3<br />

Table 2: Species numbers recorded in Mabira from each family 11<br />

Table 3: World production and consumption <strong>of</strong> sugar (million tonnes, raw value) 13<br />

Table 4: <strong>Uganda</strong> Sugar and Sugar Crops production between 2002 and 2005 15<br />

Table 5: Sugar Companies and Production in <strong>Uganda</strong> at a glance 15<br />

Table 6: Sugarcane yield in <strong>Uganda</strong>’s sugar factory nucleus estate 15<br />

Table 7: Projected sugarcane production 16<br />

Table 8: Status <strong>of</strong> land ownership <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>’s sugar factories 19<br />

Table 9: Value <strong>of</strong> sugarcane for SCOUL out-growers in Mukono district, 2006 21<br />

Table 10: Sugar production costs in selected Least Developing Countries 21<br />

Table 11: Cost structure for a Kinyara Out-grower family 24<br />

Table 12: Average out-grower’s sugarcane production returns for SCOUL 26<br />

Table 13: Value for leases <strong>of</strong> land likely to be <strong>of</strong>fered to SCOUL 28<br />

Table 14: Land resource values in Kitoola 29<br />

Table 15: Example <strong>of</strong> links between value category, functions and <strong>valuation</strong> tools 34<br />

Table 16: Value <strong>of</strong> Growing Stock 38<br />

Table 17: Value <strong>of</strong> Annual Exploitable Timber Yield 38<br />

Table 18: Value <strong>of</strong> standing Timber crop, Area Proposed for degazettement in Mabira CFR 39<br />

Table 19: Visitor statistics 42<br />

Table 21: Summary <strong>of</strong> Values 46<br />

Table 20: Carbon content and loss for tropical forest conversion 46<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

xi

List <strong>of</strong> Boxes<br />

Box 1: Out-growers production and earnings with SCOUL 20<br />

Box 2: SCOUL sets terms to abandon Mabira CFR 23<br />

Box 3: SCOUL Sugar Corporation Press release summarised 27<br />

Box 4: Kabaka Land Offer Not a Donation – Govt 27<br />

Box5: Land Resource values 28<br />

xii The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

1.0. INTRODUCTION<br />

1.1. BACKGROUND<br />

The Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> received and tabled for<br />

discussion a proposal to expand sugar production by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited (SCOUL) in<br />

2007. The key elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> proposal were to expand<br />

<strong>the</strong> acreage under sugar cane by <strong>the</strong> corporation by<br />

7,100 hactares within <strong>the</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve.<br />

The <strong>proposed</strong> expansion would however have to be<br />

preceded by <strong>the</strong> degazettement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> affected area<br />

to pave way for private use by <strong>the</strong> Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Uganda</strong> Limited.<br />

The proposal sparked <strong>of</strong>f a lot <strong>of</strong> controversy, with<br />

<strong>the</strong> key contentions centred on <strong>the</strong> clear need to<br />

conserve biodiversity and <strong>the</strong> permanent forest estate,<br />

notwithstanding <strong>the</strong> equally important need to expand<br />

sugar production to benefit from <strong>the</strong> large local, regional<br />

and international sugar commodity market.<br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve was gazetted as a central<br />

forest reserve in 1900 under <strong>the</strong> famous Buganda<br />

agreement between <strong>the</strong> British Colonizers and <strong>the</strong><br />

Buganda Kingdom. The reserve is found in Buikwe and<br />

Mukono Districts in Central <strong>Uganda</strong> and covers an area<br />

<strong>of</strong> 306 Km 2 across an altitudinal range <strong>of</strong> 1070 – 1340 m<br />

above sea level. The forest reserve is currently <strong>the</strong> largest<br />

natural high forest in <strong>the</strong> Lake Victoria crescent.<br />

The Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

hand is a limited liability company jointly owned by <strong>the</strong><br />

Mehta Family (76%) and <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

(24%). Increased sugar production by <strong>the</strong> corporation<br />

should <strong>the</strong>refore, in <strong>the</strong>ory benefit both <strong>the</strong> Mehta<br />

Family as majority shareholders and <strong>Uganda</strong>ns as<br />

minority shareholders. The converse is also true that<br />

a degradation to <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> SCOUL affects both <strong>the</strong><br />

Mehta family and <strong>Uganda</strong>ns.<br />

The Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited argues and as<br />

published in <strong>the</strong> press (The Monitor Newspaper, 2007;<br />

New Vision News Paper, 2007; East African News Paper,<br />

2007): that <strong>the</strong> allocation <strong>of</strong> an additional 7,186 ha out <strong>of</strong><br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve will:<br />

1. Increase sugar production and save foreign<br />

exchange <strong>of</strong> US$ 20 – 25m per annum.<br />

2. Enable <strong>the</strong> generation <strong>of</strong> an additional 1-12<br />

MW <strong>of</strong> electricity which can be supplied to<br />

<strong>the</strong> national grid and onward to a number <strong>of</strong><br />

industries in and around Lugazi Town.<br />

3. Create an additional 3,500 jobs with an annual<br />

earning <strong>of</strong> Shs 3 billion.<br />

4. Lead to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> additional<br />

infrastructure investments (schools, houses,<br />

dispensaries) worth Shs. 3.5 billion;<br />

5. Require <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> 300 km <strong>of</strong> road in<br />

<strong>the</strong> newly allotted areas, an investment <strong>of</strong> Shs.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 1<br />

2bn.<br />

6. Generate additional taxes in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> value<br />

added tax (VAT), Excise Duty, pay as you earn<br />

(PAYE) and import duty in <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> Shs. 11.5m<br />

(per year).<br />

7. Enable <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> ethyl alcohol which can<br />

be blended with petrol to <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> 10-15%,<br />

to form gasohol, an alternative vehicle fuel.<br />

8. Commit SCOUL and <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

not to develop any more areas near <strong>the</strong> banks<br />

<strong>of</strong> River Nile and <strong>the</strong> shores <strong>of</strong> Lake Victoria and<br />

hence preserve <strong>the</strong> ecology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> Mabira<br />

CFR.<br />

9. Commit SCOUL to participate in tree planting on<br />

those areas which are not suitable for sugarcane<br />

production.

The pro-conservation groups who are are opposed to<br />

<strong>the</strong> degazettement <strong>of</strong> part <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

hand argue that:<br />

1. Mabira Central Forest Reserve has unique bird,<br />

2<br />

plant, primate, butterfly and tree species;<br />

2. Mabira Central Forest Reserve is located in a<br />

heavily settled agricultural area close to large<br />

urban centres including Kampala, Lugazi,<br />

Mukono and Jinja. This makes it a very important<br />

refugium and eco-tourist destination;<br />

3. Whereas <strong>the</strong> forest suffered considerable<br />

destruction through illegal removal <strong>of</strong> forest<br />

produce and agricultural encroachment which<br />

activities threatened <strong>the</strong> integrity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se have now been controlled and <strong>the</strong> forest<br />

has regained its original integrity;<br />

4. The bird species list for Mabira Forest now stands<br />

at 287 species <strong>of</strong> which 109 were recorded during<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1992-1994 Forest Department Biodiversity<br />

Inventory (Davenport et al, 1996). These include<br />

three species listed as threatened by <strong>the</strong> Red Data<br />

Books (Collar et al, 1994) i.e. <strong>the</strong> blue swallow<br />

(Hirundo atrocaerulea), <strong>the</strong> papyrus Gonolek<br />

(Laniarius mufumbiri) and Nahan’s Francolin<br />

(Francolinus nahani);<br />

5. The present value <strong>of</strong> timber benefit streams<br />

obtained from long-run sustainable yield in<br />

Mabira CFR and timber values foregone in <strong>the</strong><br />

plantations <strong>of</strong> Kifu and Namyoya ; <strong>the</strong> present<br />

value <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r annual benefit streams from forest<br />

products, biodiversity, domestic water, carbon<br />

storage and ecotourism; and <strong>the</strong> present value<br />

<strong>of</strong> annual ground rent payments would have to<br />

be foregone if <strong>the</strong> land use for Mabira CFR was<br />

changed;<br />

6. The Mabira CFR in its entirerity is an important<br />

water catchment forest. The CFR is a source <strong>of</strong><br />

two main rivers – Musamya and Sezibwa – which<br />

flow into Lake Kyoga;<br />

7. Because <strong>of</strong> its strategic location close to <strong>the</strong> River<br />

Nile <strong>the</strong> Mabira CFR is a critical component <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> local and regional hydrological cycle. There is<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore a likelihood <strong>of</strong> reduced water retention<br />

<strong>of</strong> water flow to <strong>the</strong> lakes and rivers;<br />

8. A large population living in and around Mabira<br />

CFR relies on <strong>the</strong> extraction <strong>of</strong> forest products to<br />

sustain <strong>the</strong>ir livelihoods;<br />

9. <strong>Uganda</strong> is a signatory to a number <strong>of</strong> key<br />

Conventions that protect forests including <strong>the</strong><br />

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Kyoto Protocol among o<strong>the</strong>rs;<br />

10. Change <strong>of</strong> land use in part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest will make<br />

it difficult to control fu<strong>the</strong>r encroachment.<br />

11. Any degradation <strong>of</strong> Mabira represents loss <strong>of</strong> a<br />

unique ecosystem and unique biodiversity and<br />

loss <strong>of</strong> known and unknown plants and animals<br />

<strong>of</strong> medicinal value;<br />

12. Mabira contributes to temperature regulation in<br />

<strong>the</strong> central part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country, and any reduction<br />

is likely to lead to changes in temperature;<br />

13. The publicity resulting from converting part<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CFR will result in tourism becoming less<br />

attractive;<br />

14. A number <strong>of</strong> individuals, NGOs and corporations<br />

currently licensed to carry out activities in line<br />

with sustainable forest management will have<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir investment and planned activities affected;<br />

15. Investors in industrial plantations elsewhere in<br />

<strong>the</strong> country may face hostility from local people<br />

who may <strong>the</strong>mselves desire to acquire forest<br />

land, which <strong>the</strong>y see as being allocated to foreign<br />

investors;<br />

16. There are no indications that <strong>the</strong> public<br />

opposition to <strong>the</strong> degazzettement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CFR will<br />

diminish;<br />

17. There could be insecurity to <strong>the</strong> investor over<br />

Mabira allocation;<br />

18. The <strong>proposed</strong> degazettement is likely to impact<br />

negatively on <strong>the</strong> image <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country<br />

As indicated above, both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contention<br />

have strong arguments for <strong>the</strong>ir case. The arguments<br />

have however, not been translated into a common<br />

denominator to allow for impartial comparison <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

benefits and costs <strong>of</strong> degazetting part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

The purpose <strong>of</strong> this study <strong>the</strong>refore is to use <strong>economic</strong><br />

analysis to determine <strong>the</strong> merits and demerits <strong>of</strong><br />

degazettement <strong>of</strong> part <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve<br />

for sugar cane production.<br />

1.2. THE DEGAZETTEMENT PROPOSAL<br />

The request and <strong>proposed</strong> degazettement covers an<br />

area <strong>of</strong> 7100 ha <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> production zone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reserve<br />

representing about 24 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total area <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

forest. From <strong>the</strong> perspective <strong>of</strong> forest management and<br />

in order not to split any compartments, SCOUL’s request<br />

would involve <strong>the</strong> degazetting <strong>of</strong> 15 compartments,<br />

giving a total area <strong>of</strong> 7,186 hectares. The area requested<br />

by SCOUL for additional sugar production is <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

7186 ha (Table 1). This size <strong>of</strong> area will <strong>the</strong>refore be used<br />

in <strong>the</strong> analysis for purposes <strong>of</strong> this study. Figure 1 shows<br />

a spatial description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> affected area.<br />

Table 1: Mabira CFR Area Proposed for Degazettement<br />

Compartment No. Name Size (ha)<br />

171 Wakisi 617<br />

172 Senda North 315<br />

173 Senda 488<br />

174 Luwala 515<br />

175 Bugule 381<br />

178 Sango East 667<br />

179 Kyabana South 424<br />

180 Kyabana Central 451<br />

181 Kyabana North 365<br />

182 Liga 403<br />

183 Naligito 415<br />

184 Mulange 611<br />

185 Kasota 679<br />

234 Ssezibwa South 586<br />

235 Nandagi 479<br />

Totals 7186<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 3

Figure 1: Map <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR showing <strong>the</strong> Proposed sections for Degazettement<br />

B<br />

B<br />

Namulaba<br />

F/stn<br />

B<br />

Maligita F/stn<br />

Maligito<br />

Cpt 183<br />

404.813Ha<br />

Wakisi<br />

Liga<br />

Cpt 171<br />

cpt 182 613.464Ha<br />

Kyabana North<br />

Senda North<br />

cpt 181<br />

Cpt 172<br />

341.291Ha<br />

320.394Ha<br />

Naluvule F/stn<br />

262.390Ha<br />

Kyabana F/Stn<br />

Kyabana Central<br />

Cpt 180<br />

447.251Ha<br />

Kyabana South<br />

Cpt 179<br />

403.050Ha<br />

Malunge<br />

Cpt 184<br />

579.919Ha<br />

4 The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

Senda<br />

cpt 173<br />

499.419Ha<br />

Nagojje F/tsn<br />

Luwala<br />

Cpt 174<br />

516.500Ha<br />

Kasota<br />

Cpt 185<br />

694.248Ha<br />

Luwala South<br />

Cpt 175<br />

357.846Ha<br />

Sango East<br />

Cpt 178<br />

653.244Ha<br />

Sesibwa<br />

Cpt 234<br />

563 Ha<br />

Buwoola<br />

F/Stn<br />

B<br />

Wanande F/stn<br />

Najjembe F/stn<br />

B<br />

Nandagi<br />

Cpt 235<br />

442Ha<br />

Scale 1:140,000M<br />

0 2,<br />

050<br />

4,100 8,200 Meters<br />

Lwankima<br />

F/stn<br />

Outlines <strong>of</strong> blocks Forest Station Blocks <strong>proposed</strong> for degazettement

1.3 SCOPE OF THE ASSIGNMENT<br />

The overall purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study was to compare <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>economic</strong> merits <strong>of</strong> degazetting a section <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR<br />

for sugar cane growing to those <strong>of</strong> maintaining it. This<br />

comparative study required <strong>the</strong> computation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

respective costs and benefits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two alternative land<br />

uses with a view to determining <strong>the</strong> most preferable<br />

option. The benefits decision framework is summarised<br />

as follows:<br />

T<br />

T<br />

If∑ Bs∂t � ∑ Bc∂t<br />

, T<br />

T<br />

grow sugarcane; and if<br />

t = oB<br />

∂t<br />

� t = oB<br />

∂t<br />

, conserve<br />

∑<br />

t = o<br />

c<br />

Where:<br />

∑<br />

t = o<br />

s<br />

∑B s ∂t – sum <strong>of</strong> present value <strong>of</strong> net benefit <strong>of</strong> sugarcane<br />

growing<br />

∑B c ∂t – sum <strong>of</strong> present value <strong>of</strong> net benefit <strong>of</strong><br />

conservation<br />

The conceptual scope <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study limited it to <strong>the</strong><br />

most direct costs and benefits <strong>of</strong> land use change to<br />

sugar cane farming or <strong>the</strong> converse. Hence <strong>the</strong> primary<br />

analysis in this study dealt with sugar cane farming vis a<br />

vis forest conservation and applied farm gate or forest<br />

gate prices to all transactions. The estimates <strong>of</strong> all costs<br />

and benefits <strong>the</strong>refore related to sugar cane production<br />

and excluded <strong>the</strong> associated production <strong>of</strong> sugar, sugar<br />

by-products and <strong>the</strong> respective inputs.<br />

The study assessed a number <strong>of</strong> questions on <strong>the</strong> two<br />

components <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study viz? <strong>the</strong> sugar estate and <strong>the</strong><br />

forest estate. The key questions on <strong>the</strong> first component<br />

included:<br />

» What is <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> sugarcane estate <strong>of</strong> SCOUL?<br />

» Is it possible for SCOUL (and <strong>the</strong> sugar industry<br />

as a whole) to achieve increased output through<br />

options, such as increasing productivity, and<br />

increasing <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> out-growers, o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than using Mabira CFR?<br />

» Are <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sugar companies in <strong>Uganda</strong>, o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than SCOUL, able to meet <strong>the</strong> demand sought<br />

without having to convert part <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR<br />

into permanent agriculture?<br />

» Are <strong>the</strong>re alternative pieces <strong>of</strong> land, to Mabira<br />

CFR, that could be used and <strong>the</strong> implications <strong>of</strong><br />

using <strong>the</strong>se alternative lands for SCOUL?<br />

The key questions on <strong>the</strong> second component (<strong>the</strong> forest<br />

estate) included:<br />

» What annual benefit flows are associated with<br />

<strong>the</strong> Central Forest Reserve;<br />

» What are <strong>the</strong> potential consequences <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>proposed</strong> ecosystem degradation;<br />

» How will <strong>the</strong> annual flow <strong>of</strong> benefits change<br />

following <strong>the</strong> <strong>proposed</strong> degazettement?<br />

» What is <strong>the</strong> opportunity cost <strong>of</strong> maintaining <strong>the</strong><br />

forest estate?<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 5

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettment <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR<br />

___________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Figure 2: 2: Key Key Elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong> Conservation <strong>the</strong> Conservation versus Degazettement versus Degazettment Options Options <strong>of</strong> Part <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mabira Part Central<br />

Forest <strong>of</strong> Mabira Reserve Central Forest Reserve<br />

1.4. METHODOLOGY<br />

This <strong>economic</strong> analysis was carried out in three phases including a detailed review <strong>of</strong><br />

1.4. METHODOLOGY<br />

literature and media reports on <strong>the</strong> subject, assessment <strong>of</strong> standing stock and inventory<br />

This <strong>economic</strong> analysis was carried out in three phases<br />

information on <strong>the</strong> potential impact on <strong>the</strong> forest, key informant interviews, community<br />

including<br />

consultations<br />

a detailed<br />

followed<br />

review<br />

by<br />

<strong>of</strong><br />

data<br />

literature<br />

computations<br />

and media<br />

and interpretation. The study also involved<br />

reports detailed on <strong>the</strong> description subject, assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>of</strong> standing stock <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve, <strong>economic</strong><br />

and e<strong>valuation</strong> inventory <strong>of</strong> information <strong>the</strong> agricultural on <strong>the</strong> potential impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area and detailed analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sugar<br />

on commodity <strong>the</strong> forest, market. key informant interviews, community<br />

Description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR relied on literature reviews. The<br />

agricultural <strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong> relied on both budgeting techniques and cost benefit<br />

analysis, using <strong>the</strong> Net Present Value as <strong>the</strong> decision-making<br />

chapters.<br />

criteria. Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

conservation value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest estate relied on both cost benefit analysis and <strong>the</strong><br />

concept <strong>of</strong> total <strong>economic</strong> value (TEV). The detailed analytical frameworks are<br />

described in subsequent chapters.<br />

____________________________________________________________________<br />

By Yakobo Moyini, PhD<br />

6<br />

Biodiversity<br />

Conservation<br />

Down stream<br />

water services<br />

Recreation<br />

Extraction <strong>of</strong><br />

forest products<br />

Cost <strong>of</strong><br />

conservation<br />

Net decrease in<br />

ecosystem benefits<br />

Biodiversity<br />

Conservation<br />

Down stream<br />

water services<br />

Recreation<br />

Extraction <strong>of</strong><br />

forest products<br />

Decreased<br />

Biodiversity<br />

Conservation<br />

Decreased Down<br />

stream water<br />

services<br />

Decreased<br />

Recreation<br />

Reduced Extraction<br />

<strong>of</strong> forest products<br />

Less foregone cost<br />

<strong>of</strong> conservation<br />

Gross<br />

decrease in<br />

ecosystem<br />

benefits<br />

Opportunity<br />

cost <strong>of</strong><br />

foregone<br />

ecosystem<br />

benefits<br />

Cost <strong>of</strong><br />

conservation<br />

With Conservation Without Conservation Cost benefit analysis <strong>of</strong> conservation<br />

Source: Pagiola et al., (2004)<br />

decision<br />

consultations followed by data computations and<br />

interpretation. The study also involved detailed<br />

description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest<br />

Reserve, <strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> agricultural<br />

potential <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area and detailed analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sugar<br />

commodity market.<br />

Description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR relied on<br />

literature reviews. The agricultural <strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong><br />

relied on both budgeting techniques and cost benefit<br />

analysis, using <strong>the</strong> Net Present Value as <strong>the</strong> decisionmaking<br />

criteria. Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conservation value <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> forest estate relied on both cost benefit analysis and<br />

<strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> total <strong>economic</strong> value (TEV). The detailed<br />

analytical frameworks are described in subsequent<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

7

2.0. BIOPHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS<br />

OF MABIRA CFR<br />

2.1. SIZE AND LOCATION<br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve covers an area <strong>of</strong> 306<br />

square kilometers (km 2 ) (30,600ha) mostly in Mukono<br />

and Buikwe Districts <strong>of</strong> Central <strong>Uganda</strong>. The forest lies<br />

in an altitudinal range <strong>of</strong> 1,070 to 1,340 metres above<br />

sea level. The dominant vegetation in <strong>the</strong> forest may<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore be broadly classified as medium altitude moist<br />

semi-deciduous forest. Mabira CFR is predominantly a<br />

secondary forest with <strong>the</strong> most distinctive vegetation<br />

types representing sub-climax communities following<br />

several decades <strong>of</strong> human influence. Three forest types<br />

are discernable including a young forest dominated<br />

by Maesopsis eminii (about 25 percent); a successional<br />

forest represented by young mixed Celtis-Holoptelea<br />

tree species (about 60 percent) and riverine forests<br />

dominated by Baikiaea insignis (about 15 percent).<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> forest suffered extensive human<br />

interference in <strong>the</strong> seventies and early eighties, <strong>the</strong><br />

forest remains a significant conservation forest system.<br />

This report is aimed at providing a comprehensive<br />

account <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present state <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> flora and<br />

fauna <strong>of</strong> Mabira Forest Reserve in Mukono District. There<br />

has been a considerable amount <strong>of</strong> previous work in this<br />

forest and effort has been made to document all <strong>the</strong><br />

information. The main body <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> report provides fairly<br />

detailed accounts on <strong>the</strong> following taxa: plants; birds;<br />

mammals and butterflies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reserve. Compared with<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Uganda</strong>n forests, Mabira is relatively biodiverse,<br />

with total species diversity (an index <strong>of</strong> species richness<br />

per unit area) being average for all taxa except butterflies<br />

which were above average. In terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘conservation<br />

value’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species represented (based on knowledge<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir world-wide distributions and occurrence in<br />

<strong>Uganda</strong>n forests), Mabira is above average for birds, and<br />

butterflies, and average for <strong>the</strong> remaining taxa. As a basis<br />

for fur<strong>the</strong>r comparison with o<strong>the</strong>r sites, 81 species may<br />

be classified as restricted-range (recorded from no more<br />

than five <strong>Uganda</strong>n forests). Details <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity<br />

attributes <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR are presented in Annex 1.<br />

Site description<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve lies in <strong>the</strong> counties <strong>of</strong> Buikwe and<br />

Nakifuma in <strong>the</strong> administrative district <strong>of</strong> Mukono. It was<br />

established under <strong>the</strong> Buganda Agreement in 1900 and<br />

is situated between 32 52° - 33 07° E and 0 24° - 0 35° N. It<br />

is found 54 km east <strong>of</strong> Kampala and 26 km west <strong>of</strong> Jinja.<br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve is <strong>the</strong> largest remaining<br />

forest reserve in Central <strong>Uganda</strong> (Roberts, 1994) and<br />

lies in an area <strong>of</strong> gently undulating land interrupted by<br />

flat-topped hills that are remnants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient African<br />

peneplain (Howard, 1991). Although <strong>the</strong> reserve lies<br />

close to <strong>the</strong> shores <strong>of</strong> Lake Victoria it drains to <strong>the</strong> north<br />

eventually into Lake Kyoga and <strong>the</strong> Victoria Nile. The<br />

vegetation in <strong>the</strong> reserve may be classified as medium<br />

altitude moist semi-deciduous forest. The dominant tree<br />

vegetation is mostly sub-climax tree species, with clear<br />

signs <strong>of</strong> previous disturbance and human interference.<br />

The reserve has a number <strong>of</strong> community enclaves. The<br />

enclaves are however, not part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gazetted area <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> forest. Mabira Central Forest Reserve is covered by<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Lands and Surveys Department map sheets<br />

61/4, 62/3, 71/2 and 72/1 (series Y732) at 1:50,000.<br />

2.2. GEOLOGY AND SOILS<br />

Pallister (1971) indicated that <strong>the</strong> principal rock types<br />

underlying Mabira Forest Reserve are granitic gneisses<br />

and granites with overlying series <strong>of</strong> metasediments<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 7

which include schist’s, phyllites, quartzites and<br />

amphibolites. The gneisses and granites are generally<br />

fairly uniform and give rise to little variation in resistance<br />

to soil erosion o<strong>the</strong>r than along joints and fracture<br />

planes. Under humid conditions, granitic rocks are very<br />

liable to chemical decomposition and, in most parts <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> area, <strong>the</strong> rocks are now wea<strong>the</strong>red to a considerable<br />

depth. The overlying metasediments, by contrast, are<br />

heterogeneous and include hard resistant bands <strong>of</strong><br />

quartzite and, to a lesser extent, amphibolite, alternating<br />

with s<strong>of</strong>t, easily eroded schist’s.<br />

Soils<br />

The soils in <strong>the</strong> forest reserve are strongly influenced<br />

by <strong>the</strong> local topography. The forest lies on <strong>the</strong> Buganda<br />

catena which comprises <strong>of</strong> red soils with incipient<br />

laterisation? on <strong>the</strong> slopes and black clay soils in <strong>the</strong><br />

valley bottoms. There are four principal members <strong>of</strong><br />

this catena which are described as follows, starting with<br />

those at <strong>the</strong> highest altitude:<br />

a. Shallow Lithosols <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> highest ridge crests<br />

8<br />

consisting <strong>of</strong> grey and grey brown sandy loams<br />

overlying brashy, yellowish or reddish brown<br />

loam with laterite or quartzite fragments and<br />

boulders.<br />

b. Red Earths (Red Latosols) which cover most<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> land surface and are strikingly apparent<br />

in <strong>the</strong> large conical termitaria dotting a ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

monotonously green landscape. The soil pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

consists <strong>of</strong> up to 30 cm <strong>of</strong> brown sandy or clay<br />

loam overlying uniform orange-red clay to a<br />

depth <strong>of</strong> 3 m or more.<br />

c. Grey Sandy Soils appearing at <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> catena <strong>the</strong>se may be derived from<br />

hill-wash or river alluvium. Underlying <strong>the</strong> sandy<br />

topsoils are fine sandy clays <strong>of</strong> a very pale grey<br />

colour mottled to orange brown.<br />

d. Grey clay usually water logged and occupied by<br />

papyrus stand at <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> catena. Below<br />

this are sandy and even pebbly clays. Despite<br />

<strong>the</strong> waterlogged condition for most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> year,<br />

surface peat accumulation is rarely more than a<br />

few inches thick. The last two members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

catena are very acid in reaction (pH 3.8 – 4.8) and<br />

are deficient in all plant nutrients except sulphur<br />

and magnesium.<br />

Due to <strong>the</strong> wea<strong>the</strong>ring, <strong>the</strong> soils are not so fertile and<br />

<strong>the</strong> fertility that is <strong>the</strong>re is because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest litter<br />

that decomposes and releases nutrients. However, <strong>the</strong><br />

cutting away <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest will result into fur<strong>the</strong>r soil<br />

degradation because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> removal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest cover<br />

and subsequent loss <strong>of</strong> litter. It will also lead to quicker<br />

leaching <strong>of</strong> nutrients and higher soil erosion levels.<br />

2.3. PLANTS<br />

Three hunded sixty five plant species are known to occur<br />

in Mabira forest as recorded by Howard & Davenport<br />

(1996) and Ssegawa (2006). Of <strong>the</strong> species recorded in this<br />

reserve, nine are uncommon and have been recorded<br />

from not more than five <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 65 main forest reserves in<br />

<strong>Uganda</strong> (Howard & Davenport, 1996). Trees and shrubs<br />

recorded in Mabira but not previously known in <strong>the</strong><br />

floral region include Acacia hecatophylla, Aeglopsis<br />

eggelingii, Alangium chinense, Albizia glaberrima,<br />

Aningeria adolfi-friederici, Bequaertiodendron<br />

oblanceolatum, Cassipourea congensis, Celtis adolfi-<br />

fridericii, Chrysophyllum gorungosanum, Dombeya<br />

goetzenii, Drypetes bipindensis, Elaeis guineensis,<br />

Elaeophorbia drupfera, Ficus dicranostyla, Khaya<br />

antho<strong>the</strong>ca, Lannea barteri, Manilkara multinervis,<br />

Musanga cecropioides,Myrianthus holstii, Neoboutonia<br />

macrocalyx, Rawsonia lucida, Rhus ruspolii, Rinorea<br />

beniensis, Schrebera alata, Tapura fischeri and Warburgia<br />

ugandensis. Restricted-range trees and shrubs recorded<br />

from Mabira include Caesalpinia volkensii, Antrocaryon<br />

micraster, Chrysophyllum delevoyi, Elaeis guineensis,<br />

Lecaniodiscus fraxinfolius, Tricalysia bagshawei,<br />

Chrysophyllum perpulchrum, Ficus lingua and Picralima<br />

nitida. The Mahogany species namely, Entandrophrama<br />

cylindricum, Entandrophragma angolense and Khaya<br />

antho<strong>the</strong>ca are listed as globally threatened species<br />

(IUCN, 2000). O<strong>the</strong>rs include Hallea stipulosa, Lovoa<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

swynnertonii and Milicia excelsa. The species that are<br />

known to occur in Mabira forest are given in Table A1.<br />

2.4. BIRDS<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve is an Important Bird Area<br />

(Byaruhanga et al 2001), globally recognized as an<br />

important site for conservation <strong>of</strong> biodiversity (key<br />

biodiversity area) using birds as indicators. Over 300<br />

species <strong>of</strong> birds is known to occur in Mabira forest with<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> highest diversity <strong>of</strong> species in <strong>Uganda</strong>. It is<br />

<strong>the</strong> biggest block <strong>of</strong> forest in central <strong>Uganda</strong> which<br />

makes Mabira Forest a refugium <strong>of</strong> species that existed<br />

in central <strong>Uganda</strong> forests. Forty-eight per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

are forest dependent representing 45% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

total. Nahan’s Francolin (Francolinus nahani) is a globally<br />

endangered species occurring only in Mabira in central<br />

<strong>Uganda</strong>. O<strong>the</strong>r globally threatened species include Blue<br />

Swallow (Hirundo atrocaerrulea, Grey Parrot (Psittacus<br />

erithacus) and Hooded Vulture (Necrosyrtes monanchus<br />

listed as globally Vulnerable. Also listed are Papyrus<br />

Gonolek (Laniarius mufumbiri) a ‘near-threatened’<br />

species.<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve supports a rich avifauna <strong>of</strong><br />

significant conservation value. O<strong>the</strong>r regionally<br />

threatened species include Brown Snake-Eagle<br />

(Circaetus cinereus), Crowned Eagle (Stephanoaetus<br />

coronatus), White-headed Saw-wing (Psalidoprocne<br />

albiceps), Toro Olive Greenbul (Phyllastrephus<br />

hypochloris), and Green-tailed Bristlebill (Bleda eximia).<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> species are known to occur in Mabira that<br />

are o<strong>the</strong>rwise associated with different regions and<br />

altitudes. Their presence can possibly be explained by<br />

<strong>the</strong> fact that Mabira may have been connected to <strong>the</strong><br />

refugium forest once forming part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extensive<br />

forest that existed across East Africa, now isolated since<br />

its retreat. Tit Hylia (Philodornis rushiae) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> race denti<br />

is a West African species and is only known in East Africa<br />

from two specimens, both collected in Mabira (Britton,<br />

1981). Purple-throated Cuckoo Shrike (Camphephaga<br />

quiscalina) is also known from West Africa where it<br />

is uncommon. It is known in East Africa in scattered<br />

locations where it is generally found in high altitude<br />

sites. In <strong>Uganda</strong> it is also known from lower altitude<br />

sites such as Mabira and Sango Bay Forest Reserves.<br />

Two species, Fine-banded Woodpecker (Campe<strong>the</strong>ra<br />

tulibergi) and Grey Apalis (Apalis cinerea) recorded in<br />

Mabira are normally restricted to high altitude areas.<br />

Mabira is a particularly valuable forest for lowland forest<br />

species sharing many rare species with o<strong>the</strong>r lowland<br />

forests in <strong>Uganda</strong> such as Semliki National Park and<br />

Sango Bay Forest Reserve. Examples <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se include<br />

White-bellied Kingfisher (Alcedo leucogaster), Blue-<br />

headed Crested -Flycatcher (Trochocercus nitens).<br />

Restricted-range birds recorded from Mabira include<br />

Little Bittern (Ixobrychus minutus), Banded Snake Eagle<br />

(Circaetus cinerascens), African Hawk Eagle (Hieraaetus<br />

spilogaster), Gabar Goshawk (Micronisus gabar),<br />

Nahan’s Francolin(Francolinus nahani), Allen’s Gallinule<br />

(Porphyrio alleni), Caspian Plover(Charadrius asiaticus),<br />

European Cuckoo(Cuculus canorus), Madagascar Lesser<br />

Cuckoo(Cuculus rochii), Cassin’s Spinetail(Neafrapus<br />

cassini), White-bellied Kingfisher(Alcedo leucogaster),<br />

African Dwarf Kingfisher (Ispidina lecontei), Blue-<br />

cheeked Bee-eater (Merops persicus), Eurasian Roller<br />

(Coracias garrulous), Little SpottedWoodpecker<br />

(Campe<strong>the</strong>ra cailliautii), Bearded Woodpecker<br />

(Dendropicos namaquus), Blue Swallow(Hirundo<br />

atrocaerulea), Banded Martin (Riparia cincta), African<br />

Penduline Tit (Anthoscopus caroli), Purple-throated<br />

Cuckoo-Shrike (Campephaga quiscalina), Leaflove<br />

(Pyrrhurus scandens), Isabelline Wheatear (Oenan<strong>the</strong><br />

isabellina), Black-capped Apalis (Apalis nigriceps),<br />

White-winged Warbler (Bradypterus carpalis), Carru<strong>the</strong>rs’<br />

Cisticola (Cisticola carru<strong>the</strong>rsi), Stout Cisticola (Cisticola<br />

robustus), Trilling Cisticola(Cisticola woosnami), Grey<br />

Longbill (Macrosphenus concolor), Yellow Longbill<br />

(Macrosphenus flavicans), Tit Hylia (Pholidornis rushiae),<br />

Wood Warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix), Blue-headed<br />

Crested Flycatcher (Trochocercus nitens), Plain-backed<br />

Pipit(Anthus leucophrys), Papyrus Gonolek (Laniarius<br />

mufumbiri), Woodchat Shrike(Lanius senator),<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 9

Wattled Starling(Creatophora cinerea), Red-chested<br />

Sunbird(Cinnyris erythrocerca)<br />

2.5. MAMMALS<br />

A total <strong>of</strong> fifty (50) large and small mammal species<br />

are known to occur in Mabira Forest Reserve. A high<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species list are forest-dependent,<br />

and includes Deomys ferrugineus and Scutisorex<br />

somereni, closed forest-dependent specalists <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

regarded as two <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most sensitive indicators <strong>of</strong> forest<br />

disturbance. The <strong>Uganda</strong>n endemic shrew Crocidura<br />

selina, only previously recorded from Mabira Forest<br />

(Nicoll and Rathbun, 1990) has not been recorded since<br />

but has been recorded in o<strong>the</strong>r forests. Species with high<br />

conservation value include Crocidura maurisca and<br />

Casinycteris argynnis – a new record for Mabira forest.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>rs protected under <strong>the</strong> CITES include Red-tailed<br />

Monkey (Cercopi<strong>the</strong>cus ascanius), Potto (Perodictictus<br />

potto), Galago (Galago senegalensis), Leopard (Pan<strong>the</strong>ra<br />

pardus), Grey Cheeked Mangabey (Cercocebus abigena)<br />

and Baboons (Papio anubis).<br />

2.6. AMPHIBIANS<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> common amphibian species are associated<br />

with permanent wetlands, rivers or water points. Species<br />

<strong>of</strong> genera Afrana, Hyperolius, Xenopus, Hoplobatrachus<br />

and Afrixalus seem to select habitats with water all year<br />

round. The commonest species were members <strong>of</strong> family<br />

Hyperoliidae. Members <strong>of</strong> family Ranidae were also<br />

found to be common.<br />

The most common species <strong>of</strong> family Hyperoliidae<br />

are generally associated with permanent water<br />

sources. Members <strong>of</strong> genera Xenopus, Afrana and<br />

Hoplobatrachus were also quite common. Members <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se genera are commonly found near water, more so<br />

for <strong>the</strong> bullfrog, which only gets out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> water to feed.<br />

Afrana angolensis is a riverine species found mainly<br />

along rivers and this was encountered along rivers in<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve (Table A4). One member <strong>of</strong> family<br />

Arthroleptidae, Artholeptis adolfifriederici is a new<br />

record for Mabira Forest Reserve.<br />

10<br />

2.7. REPTILES<br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve has a variety <strong>of</strong> reptiles.<br />

More than 23 species <strong>of</strong> reptiles have been identified in<br />

<strong>the</strong> reserve. Reptiles are highly mobile and live in a range<br />

<strong>of</strong> habitats. They may be encountered in aquatic, bush,<br />

forest, rocky or riverine terrain. The tolerance <strong>of</strong> reptiles<br />

to a range <strong>of</strong> habitat types explains <strong>the</strong> large diversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> reptile species in <strong>the</strong> forest reserve.The key reptiles<br />

in <strong>the</strong> reserve however, include chameleons, geckos,<br />

forest and nile monitor lizards, skinks, snakes including<br />

tree and house snakes, pythons, cobras, mambas, puff<br />

adders and vipers. A list <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> key reptile species in<br />

<strong>the</strong> forest reserve toge<strong>the</strong>r with an indication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

respective conservation status is included in Table A5 in<br />

<strong>the</strong> annex.<br />

2.8. BUTTERFLIES<br />

A total <strong>of</strong> 199 species <strong>of</strong> butterflies is known to occur<br />

in Mabira forest. Nine (9) Papilioidae, twenty four (24)<br />

Pieridae, twenty five (25) Lycaenidae, one hundred<br />

and twenty eight (128) Nymphalidae aud thirteen (13)<br />

Hesperiidae. A relatively high proportion (73 percent) <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> total were forest-dependent butterflies. Details <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> species taken from each family, and each<br />

subfamily in <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Papilionidae, Pieridae and<br />

Nymphalidae, are provided in Table 2.<br />

It can be seen that <strong>the</strong> reserve supports at least 16 percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>’s Rhopaloceran fauna, including 24 percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country’s Pieridae, 29 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nymphalidae<br />

and 38 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> subfamily Charaxinae (Howard<br />

& Davenport, 1996). Of <strong>the</strong> species registered, those<br />

<strong>of</strong> particular interest included Sallya natalensis a new<br />

record for <strong>Uganda</strong> (Howard & Davenport, 1996). This<br />

butterfly is a migratory insect so unusual distribution<br />

records are not too surprising, however, its previous<br />

known range was from Natal to parts <strong>of</strong> Kenya (Larsen,<br />

1991). Charaxes boueti, meanwhile, a member <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> more commonly studied subfamilies, represents a<br />

new record for this forest (Howard & Davenport, 1996):<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few areas in <strong>the</strong> country which have been<br />

comparatively well investigated for <strong>the</strong>ir Rhopaloceran<br />

fauna.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

At least two sub-species endemic to <strong>Uganda</strong> were<br />

registered, Tanue<strong>the</strong>ira timon orientius; <strong>Uganda</strong>n<br />

forests being <strong>the</strong> eastern limit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species’ range and<br />

Acraea lycoa entebbia, known only from central and<br />

eastern <strong>Uganda</strong>. Acraea agan ice ugandae, meanwhile,<br />

an uncommon butterfly is restricted to <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

shoreline <strong>of</strong> Lake Victoria (Howard & Davenport, 1996).<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r species <strong>of</strong> limited range include <strong>the</strong> skipper<br />

Ceratrichia mabirensis (Mabira being <strong>the</strong> Type Locality)<br />

with a patchy distribution, limited to parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>,<br />

Tanzania and western Kenya (Larsen, 1991), and<br />

Pseudathyma plutonica a scarce insect ranging from<br />

eastern Democratic Republic <strong>of</strong> Congo (DRC) to western<br />

Kenya. Moreover, Fseudacraea clarki, a comparatively<br />

large and conspicuous butterfly has records from<br />

Cameroon to Gabon and West Kenya, although Larsen<br />

(1991) maintains its absence from <strong>the</strong> latter. It is certainly<br />

not a common insect in East Africa.<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve may be considered rich in terms<br />

<strong>of</strong> its butterfly fauna, supporting a high percentage <strong>of</strong><br />

forest-dependent butterflies, as well as a number <strong>of</strong><br />

uncommon and restricted-range species (Howard &<br />

Davenport, 1996). Despite a recent history <strong>of</strong> intensive<br />

human disturbance in this forest (as reflected by <strong>the</strong><br />

fact that almost a quarter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species recorded are<br />

associated with forest edge and woodland habitats), <strong>the</strong><br />

butterfly fauna has shown marked resilience (Howard &<br />

Davenport, 1996). Two species <strong>of</strong> Nymphalidae Acraea<br />

rogersi and Bicyclus mesogena, both reliant on dense,<br />

undisturbed forest demonstrate <strong>the</strong> environmental<br />

flexibility <strong>of</strong> some invertebrate communities (Howard &<br />

Davenport, 1996).<br />

Table 2: Species numbers recorded in Mabira from each family and from Papilionidae, Pieridae and<br />

Nymphalidae subfamilies<br />

Family <strong>Uganda</strong> Forest % <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

Subfamily Total Total Total<br />

Papilionidae 31 9 29<br />

Papilioninae 31 9 29<br />

Pieridae 100 24 24<br />

Coliadinae 10 3 30<br />

Pierinae 90 21 23<br />

Lycaenidae 460 25 5<br />

Nymphalidae 447 128 29<br />

Danainae 13 7 54<br />

Satyrinae 71 20 28<br />

Charaxinae 65 25 38<br />

Apaturinae 1 1 100<br />

Nymphalinae 195 50 26<br />

Acraeinae 101 24 24<br />

Liby<strong>the</strong>inae 1 1 100<br />

Hesperiidae 207 13 6<br />

TOTAL 1245 199 16<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 11

Restricted-range butterflies recorded from Mabira<br />

include Belenois victoria Victoria White, Dixeia charina<br />

African Small White, Epitola catuna, Lachnocnema<br />

bibulus Woolly Legs, Tanue<strong>the</strong>ira timon, Cacyreus<br />

audeoudi Audeoud’s Bush Blue, Amauris hecate Dusky<br />

Danaid, Charaxes port hos, Charaxes pythodoris Powder<br />

Blue Charaxes, Palla ussheri, Apaturopsis clenchares<br />

Painted Empress, Euryphura albimargo, Euryphura<br />

chalcis, Pseudathyma plutonica, Pseudacraea clarki,<br />

12<br />

Neptis trigonophora, Sallya natalensis Natal Tree<br />

Nymph, Hypolimnas dubius Variable Diadem, Acraea<br />

aganice Wanderer, Acraea rogersi Rogers’ Acraea,<br />

Acraea semivitrea, Acraea tellus, Celaenorrhinus bettoni,<br />

Celaenorrhinus proxima, Gomalia elma African Mallow<br />

Skipper, Ceratrichia mabirensis, and Caenides dacena.<br />

The list <strong>of</strong> known butterflies <strong>of</strong> Mabira forest are given<br />

in Table A6.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

3.0. ECONOMIC EVALUATION OF THE<br />

SUGAR SECTOR IN UGANDA<br />

3.1. GLOBAL SUGAR PRODUCTION<br />

TRENDS<br />

More than 130 countries produce sugar world wide. Of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se, 66 percent process <strong>the</strong>ir sugar from sugarcane.<br />

The rest produce sugar from sugar beet. Sugarcane<br />

primarily grows in <strong>the</strong> tropical and sub-tropical zones<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn hemisphere, while sugar beet is<br />

largely grown in <strong>the</strong> temperate zones <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

hemisphere (ED&F Man, 2004). Prior to 1990, about 40<br />

percent <strong>of</strong> sugar was made from beet but sugarcane<br />

production has grown more rapidly over <strong>the</strong> last two<br />

decades because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lower costs associated with its<br />

production.<br />

The top seven sugar producing countries in <strong>the</strong> world<br />

include Brazil, India, <strong>the</strong> European Union, China,<br />

Thailand, South Africa and Mauritius. The above seven<br />

countries produce up to sixty (60) percent <strong>of</strong> total global<br />

output (USDA, 2006). Projections indicate increased<br />

sugar production in 2006/07 due to higher production<br />

in Brazil, India, China and Thailand. Production in <strong>the</strong><br />

EU was expected to decline by 5 million tonnes, from<br />

21.8 million metric tonnes to 16.8 million metric tonnes<br />

(USDA, 2007).<br />

Over seventy (70) percent <strong>of</strong> global sugar production<br />

is consumed in <strong>the</strong> country <strong>of</strong> origin, implying that<br />

only thirty (30) percent is traded in <strong>the</strong> world sugar<br />

market (ED&F Man, 2004). As indicated in Table 3, world<br />

consumption <strong>of</strong> sugar was higher than production for<br />

2005 and 2006 (Table 3). Africa, Asia, Greater Europe<br />

(outside EU) and North America were <strong>the</strong> regions<br />

with <strong>the</strong> largest sugar deficit (Table 3). In Africa, <strong>the</strong><br />

deficit was 2.8 and 2.7 million tonnes in 2005 and 2006<br />

respectively (FAO, 2006). More than 60 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

global consumption <strong>of</strong> sugar takes place in developing<br />

countries, with China and India leading <strong>the</strong> way. In<br />

addition, it is <strong>the</strong> developing countries particularly in<br />