the economic valuation of the proposed ... - Nature Uganda

the economic valuation of the proposed ... - Nature Uganda

the economic valuation of the proposed ... - Nature Uganda

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

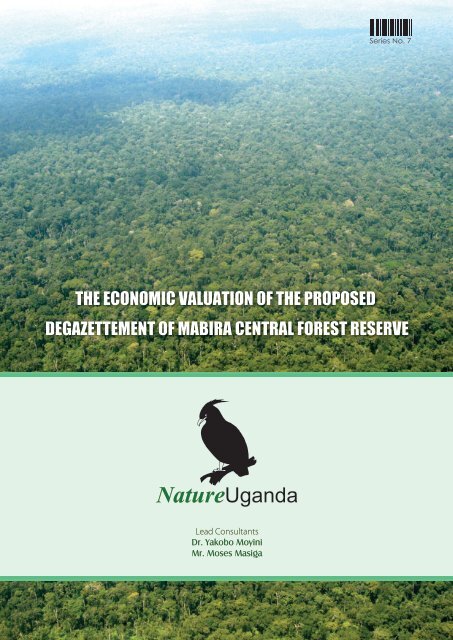

THE ECONOMIC VALUATION OF THE PROPOSED<br />

DEGAZETTEMENT OF MABIRA CENTRAL FOREST RESERVE<br />

<strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong><br />

Lead Consultants<br />

Dr. Yakobo Moyini<br />

Mr. Moses Masiga<br />

Series No. 7

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve<br />

With support from

THE ECONOMIC VALUATION OF THE<br />

PROPOSED DEGAZETTEMENT OF MABIRA<br />

CENTRAL FOREST RESERVE<br />

Reproduction <strong>of</strong> this publication for educational or o<strong>the</strong>r non commercial<br />

purposes is authorized only with fur<strong>the</strong>r written permission from <strong>the</strong> copyright<br />

holder provided <strong>the</strong> source is fully acknowledged. Production <strong>of</strong> this publication<br />

for resale or o<strong>the</strong>r commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written<br />

notice <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> copyright holder.<br />

Citation: <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> (2011). The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed<br />

Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve. <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> Kampala<br />

Copyright<br />

©<strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> – The East Africa Natural History Society<br />

P.O.Box 27034,<br />

Kampala <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

Plot 83 Tufnel Drive<br />

Kamwokya.<br />

Email nature@natureuganda.org<br />

Website: www.natureuganda.org

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

This consultancy builds on <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> earlier studies to identify important biodiversity areas in <strong>Uganda</strong> or key<br />

biodiversity areas. Thirty three (33) Important Bird Areas were identified including Mabira Forest Reserve.<br />

In this study, we make a case that policy formulation about natural resources needs to be informed with facts in <strong>the</strong><br />

present and full knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> future or predicted long term consequences. We are grateful to BirdLife<br />

International Partnership particularly Royal Society for <strong>the</strong> Protection <strong>of</strong> Birds (RSPB) whose initial support enabled<br />

<strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> to undertake this study on <strong>the</strong> <strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> a section <strong>of</strong> Mabira Forest Reserve that was<br />

<strong>proposed</strong> for Degazzettement.<br />

The research work falls under our advocacy programme supported by various partners including BirdLife International<br />

through Jansen’s Foundation programme on ‘turning policy advantages into conservation gains’. It is our sincere<br />

hope that this report will trigger and sustain informed debate on conservation value <strong>of</strong> natural resources<br />

particularly critical ecosystems such as Mabira Forest Reserve. <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> recognised <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> an<br />

<strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reseve at a time when <strong>the</strong>re was a debate pitting conservation <strong>of</strong><br />

natural resources against intensive use for agriculture and industry and this report will contribute useful information<br />

to <strong>the</strong> debate not only for Mabira Forest but for o<strong>the</strong>r natural resources in <strong>the</strong> country. We acknowledge <strong>the</strong> support<br />

received from <strong>Nature</strong><strong>Uganda</strong> secretariat especially <strong>the</strong> Executive Director Mr. Achilles Byaruhanga for coordinating<br />

<strong>the</strong> study and providing <strong>the</strong> consultants with all logistical requirements.<br />

We acknowledge contribution <strong>of</strong> Mr Telly Eugene Muramira who technically edited <strong>the</strong> report and Dr. Patrick Birungi<br />

<strong>of</strong> Makerere University for reading <strong>the</strong> earlier drafts as well as Dr. Panta Kasoma and Roger Skeen who pro<strong>of</strong> read <strong>the</strong><br />

report.<br />

Special tribute is paid to Dr. Yakobo Moyini (R.I.P) who was <strong>the</strong> lead consultant on this study that was conducted in<br />

2008. O<strong>the</strong>r persons who contributed to this report include Mr. Moses Masiga and Dr. Paul Segawa.<br />

We fur<strong>the</strong>r acknowledge EU support through <strong>the</strong> Important Bird Areas (IBA) monitoring project for providing <strong>the</strong><br />

funds towards printing <strong>of</strong> this report in 2011.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

V

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS<br />

SCOUL Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited<br />

VAT Value Added Tax<br />

PAYE Pay as You Earn<br />

CFR Central Forest Reserve<br />

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change<br />

NGO Non-Governmental Organisation<br />

CHOGM Commonwealth Heads <strong>of</strong> Government Meeting<br />

PFE Permanent Forest Estate<br />

CFR Central Forest Reserve<br />

CITES Convention on International Trade <strong>of</strong> Flora and Fauna<br />

TEV Total Economic Value<br />

NTFP Non-Timber Forest Product<br />

TCM Travel Cost Method<br />

CVM Contingent Valuation Method<br />

PV Present Value<br />

NFA National Forestry Authority<br />

FGD Focus Group Discussion<br />

RIL Reduced Impact Logging<br />

MPA Management Plan Area<br />

FD Forest Department<br />

PA Protected Area<br />

THF Tropical High Forest<br />

WTP Willingness To Pay<br />

GEF Global Environment Facility<br />

Vi The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

The Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> received and tabled for discussion a proposal to degazette and change <strong>the</strong> land use <strong>of</strong><br />

part <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve to sugar cane production. The proposal proved very contentious and resulted<br />

in civil unrest and a raging debate on <strong>the</strong> merits and demerits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>proposed</strong> land use change. Those in favour <strong>of</strong><br />

degazettement cited <strong>the</strong> numerous direct, indirect and multiplier <strong>economic</strong> impacts or benefits <strong>the</strong> change in land<br />

use will bring to <strong>Uganda</strong>. Those for conservation, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, cited <strong>the</strong> need to preserve <strong>the</strong> rich biodiversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest, and <strong>the</strong> need to respect both regional and international agreements on <strong>the</strong> conservation <strong>of</strong> forests and<br />

<strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>the</strong>rein. They also cited <strong>the</strong> public trust doctrine that charges government to manage and maintain<br />

forestry resources on behalf <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> citizens <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>.<br />

Whereas those in favour <strong>of</strong> degazettement have been quite eloquent in enumerating <strong>the</strong> <strong>economic</strong> benefits <strong>of</strong><br />

sugarcane growing, <strong>the</strong> pro-conservation groups have largely focused on <strong>the</strong> physical side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> argument and<br />

presented little <strong>economic</strong> data to support <strong>the</strong>ir arguments. The purpose <strong>of</strong> this study was to assess and compare <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>economic</strong> implications <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two competing land use options.<br />

To undertake <strong>the</strong> assessment, a Total Economic Value (TEV) framework was applied. This was in view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact that<br />

forests are complex ecosystems that generate a range <strong>of</strong> goods and services. The TEV framework is able to account<br />

for both use and non-use values <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest and elaborate <strong>the</strong>m into direct and indirect use values, option, bequest<br />

and existence values.<br />

Lack <strong>of</strong> knowledge and awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> goods and services provided by forests previously<br />

obscured <strong>the</strong> ecological and social impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conversion <strong>of</strong> forests into o<strong>the</strong>r land uses. The TEV framework helps<br />

us to understand <strong>the</strong> extent to which those who benefit from <strong>the</strong> forest or its conversion also bear <strong>the</strong> associated<br />

management costs or opportunities foregone.<br />

In undertaking this study, <strong>the</strong> biophysical attributes <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR in general and <strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> impact in particular were<br />

reviewed. The most current and relevant inventory data available for <strong>the</strong> production zone <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR was used.<br />

The <strong>economic</strong>s <strong>of</strong> sugarcane production in <strong>Uganda</strong> and globally was also reviewed. Additional data and information<br />

were derived from an extensive survey <strong>of</strong> available literature. All this background data and information were <strong>the</strong>n<br />

used to derive <strong>the</strong> total <strong>economic</strong> value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> impact area within Mabira CFR and compare it with <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

<strong>economic</strong> yield <strong>of</strong> growing sugarcane.<br />

The analysis concluded that <strong>the</strong> benefits <strong>of</strong> conserving Mabira CFR far exceeded those <strong>of</strong> sugarcane growing. The<br />

respective total <strong>economic</strong> value <strong>of</strong> conservation was estimated at US$ 45.1 compared to US$ 29.9 million which<br />

was <strong>the</strong> net present value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> annual benefits from sugar cane growing. The study <strong>the</strong>refore concluded that<br />

maintaining Mabira Central Forest Reserve under its current land use constituted a better option than sugarcane<br />

growing. This was <strong>the</strong> case when <strong>the</strong> total <strong>economic</strong> value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest was considered, but also when just timber<br />

values alone were counted. The study noted however, that <strong>the</strong> degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR could still be favoured<br />

for o<strong>the</strong>r reasons o<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>economic</strong> considerations. The study recommended that should such a situation arise,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> developer (who is SCOUL) must undertake to compensate <strong>the</strong> National Forestry Authority for <strong>the</strong> total<br />

<strong>economic</strong> value (TEV) lost due to <strong>the</strong> change <strong>of</strong> land use. This requirement for compensation is legally provided<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

Vii

for in <strong>the</strong> National Forestry and Tree Planting Act, <strong>the</strong> National Environment Act and provisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> multilateral<br />

environmental agreements, especially <strong>the</strong> Convention on Biological Diversity. The compensation would also<br />

conform to <strong>the</strong> social and environmental safeguard policies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> and its development<br />

partners, including <strong>the</strong> need to conduct a thorough environmental impact assessment (EIA). The appropriate level <strong>of</strong><br />

compensation <strong>the</strong> developer will be required to pay is US$45.1 million, payable to <strong>the</strong> NFA to support conservation<br />

activities in <strong>the</strong> remaining part <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR and o<strong>the</strong>r reserves.<br />

The study also noted that Government could also waive <strong>the</strong> requirement for compensation. The study however,<br />

noted that such an action would tantamount to provision <strong>of</strong> a subsidy to SCOUL amounting to US$45.1 million or <strong>the</strong><br />

total <strong>economic</strong> value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lost value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest due to <strong>the</strong> <strong>proposed</strong> change in land use. The waiver would also<br />

tantamount to a gross policy failure, particularly in view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> efficiency questions surrounding SCOUL.<br />

The study also noted that if <strong>the</strong> developer paid <strong>the</strong> US$45.1 million compensation, <strong>the</strong>y would in effect be purchasing<br />

7,186 ha <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR at a fairly high cost per hectare. Land in <strong>the</strong> vicinity currently goes for UShs 500,000 to 1,000,000<br />

per acre (or Ushs 1,250,000 –2,500,000 per hectare). If SCOUL were to pay UShs 2,500,000 per hectare, double <strong>the</strong><br />

upper range, <strong>the</strong> company would purchase 30,668 ha <strong>of</strong> land. For <strong>the</strong> equivalent <strong>of</strong> 7,186 ha, if SCOUL purchased <strong>the</strong><br />

land from private sources <strong>the</strong> company would pay UShs.17,965 million (or US$10.6 million), an amount less than <strong>the</strong><br />

compensation figure calculated in <strong>the</strong> study.<br />

The study finally noted that in addition to <strong>the</strong> financial and <strong>economic</strong> questions presented above, o<strong>the</strong>r equally valid<br />

issues needed fur<strong>the</strong>r investigation. They include <strong>the</strong> need for compensation at ‘fair and equal’ value, <strong>the</strong> current<br />

implied objective <strong>of</strong> national self-sufficiency in sugar production; and land acquisition options available to <strong>the</strong><br />

developer.<br />

Viii The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Acknowledgements iv<br />

Acronyms and Abbreviations v<br />

Executive Summary vi<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents vii<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Figures viii<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Tables ix<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Boxes x<br />

1.0. INTRODUCTION 1<br />

1.1. BACKGROUND 1<br />

1.2. THE Degazettement PROPOSAL 3<br />

1.3 SCOPE OF THE ASSIGNMENT 5<br />

1.4. METHODOLOGY 6<br />

2.0. BIOPHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF MABIRA CFR 7<br />

2.1. SIZE AND LOCATION 7<br />

2.2. GEOLOGY AND SOILS 7<br />

2.3. PLANTS 8<br />

2.4. BIRDS 8<br />

2.5. MAMMALS 10<br />

2.6. AMPHIBIANS 10<br />

2.7. REPTILES 10<br />

2.8. BUTTERFLIES 10<br />

3.0. ECONOMIC EVALUATION OF THE SUGAR SECTOR IN UGANDA 13<br />

3.1. Global Sugar Production Trends 13<br />

3.2 History <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sugar Industry in <strong>Uganda</strong> 14<br />

3.3 Sugar Production and Consumption Trends in <strong>Uganda</strong> 17<br />

3.4. Performance <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>’s Sugar Sector 16<br />

4.0. EVALUATION OF DECISION TO CONVERT MABIRA CFR FOR SUGARCANE<br />

PRODUCTION 18<br />

4.1 Sugar Production Model for <strong>Uganda</strong> 18<br />

4.2. The Value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sugar Sector in <strong>Uganda</strong> 20<br />

4.2.1 Value <strong>of</strong> Reproducible Tangible Assets ( sugarcane) 20<br />

4.2.2 Value <strong>of</strong> non-reproducible assets <strong>of</strong> sugar factory (Land at <strong>the</strong> Company owned nucleus<br />

sugarcane estate) 21<br />

4.3. Cost <strong>of</strong> Production and <strong>the</strong> Determinants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Competitiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sugar Sector in <strong>Uganda</strong> 22<br />

4.4. Options for Improving <strong>the</strong> Competitiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sugar Coorporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited (SCOUL) 25<br />

4.5. CONCLUSIONS 29<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

ix

5.0. THE CONSERVATION OPTION 31<br />

5.1. CONSERVATION OPTIONS FOR MANAGING FOREST RESOURCES 31<br />

5.2. CONSERVATION ECONOMICS 31<br />

5.2.1 Importance <strong>of</strong> <strong>economic</strong> <strong>valuation</strong> 31<br />

5.2.2 The Total Economic Value 32<br />

5.2.3 Analytical framework 35<br />

5.3. VALUATION 37<br />

6.0. DISCUSSIONS AND CONCLUSION 47<br />

6.1. DISCUSSIONS 47<br />

6.2. CONCLUSION 49<br />

x The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

REFERENCES 50<br />

Annexes 59<br />

Annex 1 Biodiversity Report 59<br />

Annex 2 Inventory Data 79<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Figures<br />

Figure 1 Map <strong>of</strong> Mabira and <strong>the</strong> Proposed Area for Degazettement 4<br />

Figure 2: Cost-benefit analysis <strong>of</strong> an alternate project, to continued conservation 6<br />

Figure 3: Centralised and contract farming model in sugar companies in <strong>Uganda</strong> 18<br />

Figure 4: Value chain for sugar cane to sugar 27<br />

Figure 5: Framework <strong>of</strong> specialisation for sugar industries 23<br />

Figure 6: The Total Economic Value <strong>of</strong> Forests 33<br />

Figure 7: Graphic Illustration <strong>of</strong> Willingness to Pay 37<br />

List <strong>of</strong> Tables<br />

Table 1: Mabira CFR Area Proposed for Degazettement 3<br />

Table 2: Species numbers recorded in Mabira from each family 11<br />

Table 3: World production and consumption <strong>of</strong> sugar (million tonnes, raw value) 13<br />

Table 4: <strong>Uganda</strong> Sugar and Sugar Crops production between 2002 and 2005 15<br />

Table 5: Sugar Companies and Production in <strong>Uganda</strong> at a glance 15<br />

Table 6: Sugarcane yield in <strong>Uganda</strong>’s sugar factory nucleus estate 15<br />

Table 7: Projected sugarcane production 16<br />

Table 8: Status <strong>of</strong> land ownership <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>’s sugar factories 19<br />

Table 9: Value <strong>of</strong> sugarcane for SCOUL out-growers in Mukono district, 2006 21<br />

Table 10: Sugar production costs in selected Least Developing Countries 21<br />

Table 11: Cost structure for a Kinyara Out-grower family 24<br />

Table 12: Average out-grower’s sugarcane production returns for SCOUL 26<br />

Table 13: Value for leases <strong>of</strong> land likely to be <strong>of</strong>fered to SCOUL 28<br />

Table 14: Land resource values in Kitoola 29<br />

Table 15: Example <strong>of</strong> links between value category, functions and <strong>valuation</strong> tools 34<br />

Table 16: Value <strong>of</strong> Growing Stock 38<br />

Table 17: Value <strong>of</strong> Annual Exploitable Timber Yield 38<br />

Table 18: Value <strong>of</strong> standing Timber crop, Area Proposed for degazettement in Mabira CFR 39<br />

Table 19: Visitor statistics 42<br />

Table 21: Summary <strong>of</strong> Values 46<br />

Table 20: Carbon content and loss for tropical forest conversion 46<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

xi

List <strong>of</strong> Boxes<br />

Box 1: Out-growers production and earnings with SCOUL 20<br />

Box 2: SCOUL sets terms to abandon Mabira CFR 23<br />

Box 3: SCOUL Sugar Corporation Press release summarised 27<br />

Box 4: Kabaka Land Offer Not a Donation – Govt 27<br />

Box5: Land Resource values 28<br />

xii The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

1.0. INTRODUCTION<br />

1.1. BACKGROUND<br />

The Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> received and tabled for<br />

discussion a proposal to expand sugar production by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited (SCOUL) in<br />

2007. The key elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> proposal were to expand<br />

<strong>the</strong> acreage under sugar cane by <strong>the</strong> corporation by<br />

7,100 hactares within <strong>the</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve.<br />

The <strong>proposed</strong> expansion would however have to be<br />

preceded by <strong>the</strong> degazettement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> affected area<br />

to pave way for private use by <strong>the</strong> Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Uganda</strong> Limited.<br />

The proposal sparked <strong>of</strong>f a lot <strong>of</strong> controversy, with<br />

<strong>the</strong> key contentions centred on <strong>the</strong> clear need to<br />

conserve biodiversity and <strong>the</strong> permanent forest estate,<br />

notwithstanding <strong>the</strong> equally important need to expand<br />

sugar production to benefit from <strong>the</strong> large local, regional<br />

and international sugar commodity market.<br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve was gazetted as a central<br />

forest reserve in 1900 under <strong>the</strong> famous Buganda<br />

agreement between <strong>the</strong> British Colonizers and <strong>the</strong><br />

Buganda Kingdom. The reserve is found in Buikwe and<br />

Mukono Districts in Central <strong>Uganda</strong> and covers an area<br />

<strong>of</strong> 306 Km 2 across an altitudinal range <strong>of</strong> 1070 – 1340 m<br />

above sea level. The forest reserve is currently <strong>the</strong> largest<br />

natural high forest in <strong>the</strong> Lake Victoria crescent.<br />

The Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

hand is a limited liability company jointly owned by <strong>the</strong><br />

Mehta Family (76%) and <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

(24%). Increased sugar production by <strong>the</strong> corporation<br />

should <strong>the</strong>refore, in <strong>the</strong>ory benefit both <strong>the</strong> Mehta<br />

Family as majority shareholders and <strong>Uganda</strong>ns as<br />

minority shareholders. The converse is also true that<br />

a degradation to <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> SCOUL affects both <strong>the</strong><br />

Mehta family and <strong>Uganda</strong>ns.<br />

The Sugar Corporation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Limited argues and as<br />

published in <strong>the</strong> press (The Monitor Newspaper, 2007;<br />

New Vision News Paper, 2007; East African News Paper,<br />

2007): that <strong>the</strong> allocation <strong>of</strong> an additional 7,186 ha out <strong>of</strong><br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve will:<br />

1. Increase sugar production and save foreign<br />

exchange <strong>of</strong> US$ 20 – 25m per annum.<br />

2. Enable <strong>the</strong> generation <strong>of</strong> an additional 1-12<br />

MW <strong>of</strong> electricity which can be supplied to<br />

<strong>the</strong> national grid and onward to a number <strong>of</strong><br />

industries in and around Lugazi Town.<br />

3. Create an additional 3,500 jobs with an annual<br />

earning <strong>of</strong> Shs 3 billion.<br />

4. Lead to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> additional<br />

infrastructure investments (schools, houses,<br />

dispensaries) worth Shs. 3.5 billion;<br />

5. Require <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> 300 km <strong>of</strong> road in<br />

<strong>the</strong> newly allotted areas, an investment <strong>of</strong> Shs.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 1<br />

2bn.<br />

6. Generate additional taxes in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> value<br />

added tax (VAT), Excise Duty, pay as you earn<br />

(PAYE) and import duty in <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> Shs. 11.5m<br />

(per year).<br />

7. Enable <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> ethyl alcohol which can<br />

be blended with petrol to <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> 10-15%,<br />

to form gasohol, an alternative vehicle fuel.<br />

8. Commit SCOUL and <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

not to develop any more areas near <strong>the</strong> banks<br />

<strong>of</strong> River Nile and <strong>the</strong> shores <strong>of</strong> Lake Victoria and<br />

hence preserve <strong>the</strong> ecology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> Mabira<br />

CFR.<br />

9. Commit SCOUL to participate in tree planting on<br />

those areas which are not suitable for sugarcane<br />

production.

The pro-conservation groups who are are opposed to<br />

<strong>the</strong> degazettement <strong>of</strong> part <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

hand argue that:<br />

1. Mabira Central Forest Reserve has unique bird,<br />

2<br />

plant, primate, butterfly and tree species;<br />

2. Mabira Central Forest Reserve is located in a<br />

heavily settled agricultural area close to large<br />

urban centres including Kampala, Lugazi,<br />

Mukono and Jinja. This makes it a very important<br />

refugium and eco-tourist destination;<br />

3. Whereas <strong>the</strong> forest suffered considerable<br />

destruction through illegal removal <strong>of</strong> forest<br />

produce and agricultural encroachment which<br />

activities threatened <strong>the</strong> integrity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se have now been controlled and <strong>the</strong> forest<br />

has regained its original integrity;<br />

4. The bird species list for Mabira Forest now stands<br />

at 287 species <strong>of</strong> which 109 were recorded during<br />

<strong>the</strong> 1992-1994 Forest Department Biodiversity<br />

Inventory (Davenport et al, 1996). These include<br />

three species listed as threatened by <strong>the</strong> Red Data<br />

Books (Collar et al, 1994) i.e. <strong>the</strong> blue swallow<br />

(Hirundo atrocaerulea), <strong>the</strong> papyrus Gonolek<br />

(Laniarius mufumbiri) and Nahan’s Francolin<br />

(Francolinus nahani);<br />

5. The present value <strong>of</strong> timber benefit streams<br />

obtained from long-run sustainable yield in<br />

Mabira CFR and timber values foregone in <strong>the</strong><br />

plantations <strong>of</strong> Kifu and Namyoya ; <strong>the</strong> present<br />

value <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r annual benefit streams from forest<br />

products, biodiversity, domestic water, carbon<br />

storage and ecotourism; and <strong>the</strong> present value<br />

<strong>of</strong> annual ground rent payments would have to<br />

be foregone if <strong>the</strong> land use for Mabira CFR was<br />

changed;<br />

6. The Mabira CFR in its entirerity is an important<br />

water catchment forest. The CFR is a source <strong>of</strong><br />

two main rivers – Musamya and Sezibwa – which<br />

flow into Lake Kyoga;<br />

7. Because <strong>of</strong> its strategic location close to <strong>the</strong> River<br />

Nile <strong>the</strong> Mabira CFR is a critical component <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> local and regional hydrological cycle. There is<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore a likelihood <strong>of</strong> reduced water retention<br />

<strong>of</strong> water flow to <strong>the</strong> lakes and rivers;<br />

8. A large population living in and around Mabira<br />

CFR relies on <strong>the</strong> extraction <strong>of</strong> forest products to<br />

sustain <strong>the</strong>ir livelihoods;<br />

9. <strong>Uganda</strong> is a signatory to a number <strong>of</strong> key<br />

Conventions that protect forests including <strong>the</strong><br />

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Kyoto Protocol among o<strong>the</strong>rs;<br />

10. Change <strong>of</strong> land use in part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest will make<br />

it difficult to control fu<strong>the</strong>r encroachment.<br />

11. Any degradation <strong>of</strong> Mabira represents loss <strong>of</strong> a<br />

unique ecosystem and unique biodiversity and<br />

loss <strong>of</strong> known and unknown plants and animals<br />

<strong>of</strong> medicinal value;<br />

12. Mabira contributes to temperature regulation in<br />

<strong>the</strong> central part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country, and any reduction<br />

is likely to lead to changes in temperature;<br />

13. The publicity resulting from converting part<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CFR will result in tourism becoming less<br />

attractive;<br />

14. A number <strong>of</strong> individuals, NGOs and corporations<br />

currently licensed to carry out activities in line<br />

with sustainable forest management will have<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir investment and planned activities affected;<br />

15. Investors in industrial plantations elsewhere in<br />

<strong>the</strong> country may face hostility from local people<br />

who may <strong>the</strong>mselves desire to acquire forest<br />

land, which <strong>the</strong>y see as being allocated to foreign<br />

investors;<br />

16. There are no indications that <strong>the</strong> public<br />

opposition to <strong>the</strong> degazzettement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CFR will<br />

diminish;<br />

17. There could be insecurity to <strong>the</strong> investor over<br />

Mabira allocation;<br />

18. The <strong>proposed</strong> degazettement is likely to impact<br />

negatively on <strong>the</strong> image <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country<br />

As indicated above, both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contention<br />

have strong arguments for <strong>the</strong>ir case. The arguments<br />

have however, not been translated into a common<br />

denominator to allow for impartial comparison <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

benefits and costs <strong>of</strong> degazetting part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

The purpose <strong>of</strong> this study <strong>the</strong>refore is to use <strong>economic</strong><br />

analysis to determine <strong>the</strong> merits and demerits <strong>of</strong><br />

degazettement <strong>of</strong> part <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve<br />

for sugar cane production.<br />

1.2. THE DEGAZETTEMENT PROPOSAL<br />

The request and <strong>proposed</strong> degazettement covers an<br />

area <strong>of</strong> 7100 ha <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> production zone <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reserve<br />

representing about 24 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> total area <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

forest. From <strong>the</strong> perspective <strong>of</strong> forest management and<br />

in order not to split any compartments, SCOUL’s request<br />

would involve <strong>the</strong> degazetting <strong>of</strong> 15 compartments,<br />

giving a total area <strong>of</strong> 7,186 hectares. The area requested<br />

by SCOUL for additional sugar production is <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

7186 ha (Table 1). This size <strong>of</strong> area will <strong>the</strong>refore be used<br />

in <strong>the</strong> analysis for purposes <strong>of</strong> this study. Figure 1 shows<br />

a spatial description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> affected area.<br />

Table 1: Mabira CFR Area Proposed for Degazettement<br />

Compartment No. Name Size (ha)<br />

171 Wakisi 617<br />

172 Senda North 315<br />

173 Senda 488<br />

174 Luwala 515<br />

175 Bugule 381<br />

178 Sango East 667<br />

179 Kyabana South 424<br />

180 Kyabana Central 451<br />

181 Kyabana North 365<br />

182 Liga 403<br />

183 Naligito 415<br />

184 Mulange 611<br />

185 Kasota 679<br />

234 Ssezibwa South 586<br />

235 Nandagi 479<br />

Totals 7186<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 3

Figure 1: Map <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR showing <strong>the</strong> Proposed sections for Degazettement<br />

B<br />

B<br />

Namulaba<br />

F/stn<br />

B<br />

Maligita F/stn<br />

Maligito<br />

Cpt 183<br />

404.813Ha<br />

Wakisi<br />

Liga<br />

Cpt 171<br />

cpt 182 613.464Ha<br />

Kyabana North<br />

Senda North<br />

cpt 181<br />

Cpt 172<br />

341.291Ha<br />

320.394Ha<br />

Naluvule F/stn<br />

262.390Ha<br />

Kyabana F/Stn<br />

Kyabana Central<br />

Cpt 180<br />

447.251Ha<br />

Kyabana South<br />

Cpt 179<br />

403.050Ha<br />

Malunge<br />

Cpt 184<br />

579.919Ha<br />

4 The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

Senda<br />

cpt 173<br />

499.419Ha<br />

Nagojje F/tsn<br />

Luwala<br />

Cpt 174<br />

516.500Ha<br />

Kasota<br />

Cpt 185<br />

694.248Ha<br />

Luwala South<br />

Cpt 175<br />

357.846Ha<br />

Sango East<br />

Cpt 178<br />

653.244Ha<br />

Sesibwa<br />

Cpt 234<br />

563 Ha<br />

Buwoola<br />

F/Stn<br />

B<br />

Wanande F/stn<br />

Najjembe F/stn<br />

B<br />

Nandagi<br />

Cpt 235<br />

442Ha<br />

Scale 1:140,000M<br />

0 2,<br />

050<br />

4,100 8,200 Meters<br />

Lwankima<br />

F/stn<br />

Outlines <strong>of</strong> blocks Forest Station Blocks <strong>proposed</strong> for degazettement

1.3 SCOPE OF THE ASSIGNMENT<br />

The overall purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study was to compare <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>economic</strong> merits <strong>of</strong> degazetting a section <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR<br />

for sugar cane growing to those <strong>of</strong> maintaining it. This<br />

comparative study required <strong>the</strong> computation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

respective costs and benefits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two alternative land<br />

uses with a view to determining <strong>the</strong> most preferable<br />

option. The benefits decision framework is summarised<br />

as follows:<br />

T<br />

T<br />

If∑ Bs∂t � ∑ Bc∂t<br />

, T<br />

T<br />

grow sugarcane; and if<br />

t = oB<br />

∂t<br />

� t = oB<br />

∂t<br />

, conserve<br />

∑<br />

t = o<br />

c<br />

Where:<br />

∑<br />

t = o<br />

s<br />

∑B s ∂t – sum <strong>of</strong> present value <strong>of</strong> net benefit <strong>of</strong> sugarcane<br />

growing<br />

∑B c ∂t – sum <strong>of</strong> present value <strong>of</strong> net benefit <strong>of</strong><br />

conservation<br />

The conceptual scope <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study limited it to <strong>the</strong><br />

most direct costs and benefits <strong>of</strong> land use change to<br />

sugar cane farming or <strong>the</strong> converse. Hence <strong>the</strong> primary<br />

analysis in this study dealt with sugar cane farming vis a<br />

vis forest conservation and applied farm gate or forest<br />

gate prices to all transactions. The estimates <strong>of</strong> all costs<br />

and benefits <strong>the</strong>refore related to sugar cane production<br />

and excluded <strong>the</strong> associated production <strong>of</strong> sugar, sugar<br />

by-products and <strong>the</strong> respective inputs.<br />

The study assessed a number <strong>of</strong> questions on <strong>the</strong> two<br />

components <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study viz? <strong>the</strong> sugar estate and <strong>the</strong><br />

forest estate. The key questions on <strong>the</strong> first component<br />

included:<br />

» What is <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> sugarcane estate <strong>of</strong> SCOUL?<br />

» Is it possible for SCOUL (and <strong>the</strong> sugar industry<br />

as a whole) to achieve increased output through<br />

options, such as increasing productivity, and<br />

increasing <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> out-growers, o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than using Mabira CFR?<br />

» Are <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sugar companies in <strong>Uganda</strong>, o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than SCOUL, able to meet <strong>the</strong> demand sought<br />

without having to convert part <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR<br />

into permanent agriculture?<br />

» Are <strong>the</strong>re alternative pieces <strong>of</strong> land, to Mabira<br />

CFR, that could be used and <strong>the</strong> implications <strong>of</strong><br />

using <strong>the</strong>se alternative lands for SCOUL?<br />

The key questions on <strong>the</strong> second component (<strong>the</strong> forest<br />

estate) included:<br />

» What annual benefit flows are associated with<br />

<strong>the</strong> Central Forest Reserve;<br />

» What are <strong>the</strong> potential consequences <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>proposed</strong> ecosystem degradation;<br />

» How will <strong>the</strong> annual flow <strong>of</strong> benefits change<br />

following <strong>the</strong> <strong>proposed</strong> degazettement?<br />

» What is <strong>the</strong> opportunity cost <strong>of</strong> maintaining <strong>the</strong><br />

forest estate?<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 5

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettment <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR<br />

___________________________________________________________________________________<br />

Figure 2: 2: Key Key Elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong> Conservation <strong>the</strong> Conservation versus Degazettement versus Degazettment Options Options <strong>of</strong> Part <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mabira Part Central<br />

Forest <strong>of</strong> Mabira Reserve Central Forest Reserve<br />

1.4. METHODOLOGY<br />

This <strong>economic</strong> analysis was carried out in three phases including a detailed review <strong>of</strong><br />

1.4. METHODOLOGY<br />

literature and media reports on <strong>the</strong> subject, assessment <strong>of</strong> standing stock and inventory<br />

This <strong>economic</strong> analysis was carried out in three phases<br />

information on <strong>the</strong> potential impact on <strong>the</strong> forest, key informant interviews, community<br />

including<br />

consultations<br />

a detailed<br />

followed<br />

review<br />

by<br />

<strong>of</strong><br />

data<br />

literature<br />

computations<br />

and media<br />

and interpretation. The study also involved<br />

reports detailed on <strong>the</strong> description subject, assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>of</strong> standing stock <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest Reserve, <strong>economic</strong><br />

and e<strong>valuation</strong> inventory <strong>of</strong> information <strong>the</strong> agricultural on <strong>the</strong> potential impact <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area and detailed analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sugar<br />

on commodity <strong>the</strong> forest, market. key informant interviews, community<br />

Description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR relied on literature reviews. The<br />

agricultural <strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong> relied on both budgeting techniques and cost benefit<br />

analysis, using <strong>the</strong> Net Present Value as <strong>the</strong> decision-making<br />

chapters.<br />

criteria. Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

conservation value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest estate relied on both cost benefit analysis and <strong>the</strong><br />

concept <strong>of</strong> total <strong>economic</strong> value (TEV). The detailed analytical frameworks are<br />

described in subsequent chapters.<br />

____________________________________________________________________<br />

By Yakobo Moyini, PhD<br />

6<br />

Biodiversity<br />

Conservation<br />

Down stream<br />

water services<br />

Recreation<br />

Extraction <strong>of</strong><br />

forest products<br />

Cost <strong>of</strong><br />

conservation<br />

Net decrease in<br />

ecosystem benefits<br />

Biodiversity<br />

Conservation<br />

Down stream<br />

water services<br />

Recreation<br />

Extraction <strong>of</strong><br />

forest products<br />

Decreased<br />

Biodiversity<br />

Conservation<br />

Decreased Down<br />

stream water<br />

services<br />

Decreased<br />

Recreation<br />

Reduced Extraction<br />

<strong>of</strong> forest products<br />

Less foregone cost<br />

<strong>of</strong> conservation<br />

Gross<br />

decrease in<br />

ecosystem<br />

benefits<br />

Opportunity<br />

cost <strong>of</strong><br />

foregone<br />

ecosystem<br />

benefits<br />

Cost <strong>of</strong><br />

conservation<br />

With Conservation Without Conservation Cost benefit analysis <strong>of</strong> conservation<br />

Source: Pagiola et al., (2004)<br />

decision<br />

consultations followed by data computations and<br />

interpretation. The study also involved detailed<br />

description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>of</strong> Mabira Central Forest<br />

Reserve, <strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> agricultural<br />

potential <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> area and detailed analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sugar<br />

commodity market.<br />

Description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR relied on<br />

literature reviews. The agricultural <strong>economic</strong> e<strong>valuation</strong><br />

relied on both budgeting techniques and cost benefit<br />

analysis, using <strong>the</strong> Net Present Value as <strong>the</strong> decisionmaking<br />

criteria. Assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> conservation value <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> forest estate relied on both cost benefit analysis and<br />

<strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> total <strong>economic</strong> value (TEV). The detailed<br />

analytical frameworks are described in subsequent<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011<br />

7

2.0. BIOPHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS<br />

OF MABIRA CFR<br />

2.1. SIZE AND LOCATION<br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve covers an area <strong>of</strong> 306<br />

square kilometers (km 2 ) (30,600ha) mostly in Mukono<br />

and Buikwe Districts <strong>of</strong> Central <strong>Uganda</strong>. The forest lies<br />

in an altitudinal range <strong>of</strong> 1,070 to 1,340 metres above<br />

sea level. The dominant vegetation in <strong>the</strong> forest may<br />

<strong>the</strong>refore be broadly classified as medium altitude moist<br />

semi-deciduous forest. Mabira CFR is predominantly a<br />

secondary forest with <strong>the</strong> most distinctive vegetation<br />

types representing sub-climax communities following<br />

several decades <strong>of</strong> human influence. Three forest types<br />

are discernable including a young forest dominated<br />

by Maesopsis eminii (about 25 percent); a successional<br />

forest represented by young mixed Celtis-Holoptelea<br />

tree species (about 60 percent) and riverine forests<br />

dominated by Baikiaea insignis (about 15 percent).<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> forest suffered extensive human<br />

interference in <strong>the</strong> seventies and early eighties, <strong>the</strong><br />

forest remains a significant conservation forest system.<br />

This report is aimed at providing a comprehensive<br />

account <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present state <strong>of</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> flora and<br />

fauna <strong>of</strong> Mabira Forest Reserve in Mukono District. There<br />

has been a considerable amount <strong>of</strong> previous work in this<br />

forest and effort has been made to document all <strong>the</strong><br />

information. The main body <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> report provides fairly<br />

detailed accounts on <strong>the</strong> following taxa: plants; birds;<br />

mammals and butterflies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reserve. Compared with<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Uganda</strong>n forests, Mabira is relatively biodiverse,<br />

with total species diversity (an index <strong>of</strong> species richness<br />

per unit area) being average for all taxa except butterflies<br />

which were above average. In terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘conservation<br />

value’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species represented (based on knowledge<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir world-wide distributions and occurrence in<br />

<strong>Uganda</strong>n forests), Mabira is above average for birds, and<br />

butterflies, and average for <strong>the</strong> remaining taxa. As a basis<br />

for fur<strong>the</strong>r comparison with o<strong>the</strong>r sites, 81 species may<br />

be classified as restricted-range (recorded from no more<br />

than five <strong>Uganda</strong>n forests). Details <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> biodiversity<br />

attributes <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR are presented in Annex 1.<br />

Site description<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve lies in <strong>the</strong> counties <strong>of</strong> Buikwe and<br />

Nakifuma in <strong>the</strong> administrative district <strong>of</strong> Mukono. It was<br />

established under <strong>the</strong> Buganda Agreement in 1900 and<br />

is situated between 32 52° - 33 07° E and 0 24° - 0 35° N. It<br />

is found 54 km east <strong>of</strong> Kampala and 26 km west <strong>of</strong> Jinja.<br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve is <strong>the</strong> largest remaining<br />

forest reserve in Central <strong>Uganda</strong> (Roberts, 1994) and<br />

lies in an area <strong>of</strong> gently undulating land interrupted by<br />

flat-topped hills that are remnants <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancient African<br />

peneplain (Howard, 1991). Although <strong>the</strong> reserve lies<br />

close to <strong>the</strong> shores <strong>of</strong> Lake Victoria it drains to <strong>the</strong> north<br />

eventually into Lake Kyoga and <strong>the</strong> Victoria Nile. The<br />

vegetation in <strong>the</strong> reserve may be classified as medium<br />

altitude moist semi-deciduous forest. The dominant tree<br />

vegetation is mostly sub-climax tree species, with clear<br />

signs <strong>of</strong> previous disturbance and human interference.<br />

The reserve has a number <strong>of</strong> community enclaves. The<br />

enclaves are however, not part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gazetted area <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> forest. Mabira Central Forest Reserve is covered by<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong> Lands and Surveys Department map sheets<br />

61/4, 62/3, 71/2 and 72/1 (series Y732) at 1:50,000.<br />

2.2. GEOLOGY AND SOILS<br />

Pallister (1971) indicated that <strong>the</strong> principal rock types<br />

underlying Mabira Forest Reserve are granitic gneisses<br />

and granites with overlying series <strong>of</strong> metasediments<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 7

which include schist’s, phyllites, quartzites and<br />

amphibolites. The gneisses and granites are generally<br />

fairly uniform and give rise to little variation in resistance<br />

to soil erosion o<strong>the</strong>r than along joints and fracture<br />

planes. Under humid conditions, granitic rocks are very<br />

liable to chemical decomposition and, in most parts <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> area, <strong>the</strong> rocks are now wea<strong>the</strong>red to a considerable<br />

depth. The overlying metasediments, by contrast, are<br />

heterogeneous and include hard resistant bands <strong>of</strong><br />

quartzite and, to a lesser extent, amphibolite, alternating<br />

with s<strong>of</strong>t, easily eroded schist’s.<br />

Soils<br />

The soils in <strong>the</strong> forest reserve are strongly influenced<br />

by <strong>the</strong> local topography. The forest lies on <strong>the</strong> Buganda<br />

catena which comprises <strong>of</strong> red soils with incipient<br />

laterisation? on <strong>the</strong> slopes and black clay soils in <strong>the</strong><br />

valley bottoms. There are four principal members <strong>of</strong><br />

this catena which are described as follows, starting with<br />

those at <strong>the</strong> highest altitude:<br />

a. Shallow Lithosols <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> highest ridge crests<br />

8<br />

consisting <strong>of</strong> grey and grey brown sandy loams<br />

overlying brashy, yellowish or reddish brown<br />

loam with laterite or quartzite fragments and<br />

boulders.<br />

b. Red Earths (Red Latosols) which cover most<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> land surface and are strikingly apparent<br />

in <strong>the</strong> large conical termitaria dotting a ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

monotonously green landscape. The soil pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

consists <strong>of</strong> up to 30 cm <strong>of</strong> brown sandy or clay<br />

loam overlying uniform orange-red clay to a<br />

depth <strong>of</strong> 3 m or more.<br />

c. Grey Sandy Soils appearing at <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

slopes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> catena <strong>the</strong>se may be derived from<br />

hill-wash or river alluvium. Underlying <strong>the</strong> sandy<br />

topsoils are fine sandy clays <strong>of</strong> a very pale grey<br />

colour mottled to orange brown.<br />

d. Grey clay usually water logged and occupied by<br />

papyrus stand at <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> catena. Below<br />

this are sandy and even pebbly clays. Despite<br />

<strong>the</strong> waterlogged condition for most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> year,<br />

surface peat accumulation is rarely more than a<br />

few inches thick. The last two members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

catena are very acid in reaction (pH 3.8 – 4.8) and<br />

are deficient in all plant nutrients except sulphur<br />

and magnesium.<br />

Due to <strong>the</strong> wea<strong>the</strong>ring, <strong>the</strong> soils are not so fertile and<br />

<strong>the</strong> fertility that is <strong>the</strong>re is because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest litter<br />

that decomposes and releases nutrients. However, <strong>the</strong><br />

cutting away <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest will result into fur<strong>the</strong>r soil<br />

degradation because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> removal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forest cover<br />

and subsequent loss <strong>of</strong> litter. It will also lead to quicker<br />

leaching <strong>of</strong> nutrients and higher soil erosion levels.<br />

2.3. PLANTS<br />

Three hunded sixty five plant species are known to occur<br />

in Mabira forest as recorded by Howard & Davenport<br />

(1996) and Ssegawa (2006). Of <strong>the</strong> species recorded in this<br />

reserve, nine are uncommon and have been recorded<br />

from not more than five <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 65 main forest reserves in<br />

<strong>Uganda</strong> (Howard & Davenport, 1996). Trees and shrubs<br />

recorded in Mabira but not previously known in <strong>the</strong><br />

floral region include Acacia hecatophylla, Aeglopsis<br />

eggelingii, Alangium chinense, Albizia glaberrima,<br />

Aningeria adolfi-friederici, Bequaertiodendron<br />

oblanceolatum, Cassipourea congensis, Celtis adolfi-<br />

fridericii, Chrysophyllum gorungosanum, Dombeya<br />

goetzenii, Drypetes bipindensis, Elaeis guineensis,<br />

Elaeophorbia drupfera, Ficus dicranostyla, Khaya<br />

antho<strong>the</strong>ca, Lannea barteri, Manilkara multinervis,<br />

Musanga cecropioides,Myrianthus holstii, Neoboutonia<br />

macrocalyx, Rawsonia lucida, Rhus ruspolii, Rinorea<br />

beniensis, Schrebera alata, Tapura fischeri and Warburgia<br />

ugandensis. Restricted-range trees and shrubs recorded<br />

from Mabira include Caesalpinia volkensii, Antrocaryon<br />

micraster, Chrysophyllum delevoyi, Elaeis guineensis,<br />

Lecaniodiscus fraxinfolius, Tricalysia bagshawei,<br />

Chrysophyllum perpulchrum, Ficus lingua and Picralima<br />

nitida. The Mahogany species namely, Entandrophrama<br />

cylindricum, Entandrophragma angolense and Khaya<br />

antho<strong>the</strong>ca are listed as globally threatened species<br />

(IUCN, 2000). O<strong>the</strong>rs include Hallea stipulosa, Lovoa<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

swynnertonii and Milicia excelsa. The species that are<br />

known to occur in Mabira forest are given in Table A1.<br />

2.4. BIRDS<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve is an Important Bird Area<br />

(Byaruhanga et al 2001), globally recognized as an<br />

important site for conservation <strong>of</strong> biodiversity (key<br />

biodiversity area) using birds as indicators. Over 300<br />

species <strong>of</strong> birds is known to occur in Mabira forest with<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> highest diversity <strong>of</strong> species in <strong>Uganda</strong>. It is<br />

<strong>the</strong> biggest block <strong>of</strong> forest in central <strong>Uganda</strong> which<br />

makes Mabira Forest a refugium <strong>of</strong> species that existed<br />

in central <strong>Uganda</strong> forests. Forty-eight per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

are forest dependent representing 45% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

total. Nahan’s Francolin (Francolinus nahani) is a globally<br />

endangered species occurring only in Mabira in central<br />

<strong>Uganda</strong>. O<strong>the</strong>r globally threatened species include Blue<br />

Swallow (Hirundo atrocaerrulea, Grey Parrot (Psittacus<br />

erithacus) and Hooded Vulture (Necrosyrtes monanchus<br />

listed as globally Vulnerable. Also listed are Papyrus<br />

Gonolek (Laniarius mufumbiri) a ‘near-threatened’<br />

species.<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve supports a rich avifauna <strong>of</strong><br />

significant conservation value. O<strong>the</strong>r regionally<br />

threatened species include Brown Snake-Eagle<br />

(Circaetus cinereus), Crowned Eagle (Stephanoaetus<br />

coronatus), White-headed Saw-wing (Psalidoprocne<br />

albiceps), Toro Olive Greenbul (Phyllastrephus<br />

hypochloris), and Green-tailed Bristlebill (Bleda eximia).<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> species are known to occur in Mabira that<br />

are o<strong>the</strong>rwise associated with different regions and<br />

altitudes. Their presence can possibly be explained by<br />

<strong>the</strong> fact that Mabira may have been connected to <strong>the</strong><br />

refugium forest once forming part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> extensive<br />

forest that existed across East Africa, now isolated since<br />

its retreat. Tit Hylia (Philodornis rushiae) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> race denti<br />

is a West African species and is only known in East Africa<br />

from two specimens, both collected in Mabira (Britton,<br />

1981). Purple-throated Cuckoo Shrike (Camphephaga<br />

quiscalina) is also known from West Africa where it<br />

is uncommon. It is known in East Africa in scattered<br />

locations where it is generally found in high altitude<br />

sites. In <strong>Uganda</strong> it is also known from lower altitude<br />

sites such as Mabira and Sango Bay Forest Reserves.<br />

Two species, Fine-banded Woodpecker (Campe<strong>the</strong>ra<br />

tulibergi) and Grey Apalis (Apalis cinerea) recorded in<br />

Mabira are normally restricted to high altitude areas.<br />

Mabira is a particularly valuable forest for lowland forest<br />

species sharing many rare species with o<strong>the</strong>r lowland<br />

forests in <strong>Uganda</strong> such as Semliki National Park and<br />

Sango Bay Forest Reserve. Examples <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se include<br />

White-bellied Kingfisher (Alcedo leucogaster), Blue-<br />

headed Crested -Flycatcher (Trochocercus nitens).<br />

Restricted-range birds recorded from Mabira include<br />

Little Bittern (Ixobrychus minutus), Banded Snake Eagle<br />

(Circaetus cinerascens), African Hawk Eagle (Hieraaetus<br />

spilogaster), Gabar Goshawk (Micronisus gabar),<br />

Nahan’s Francolin(Francolinus nahani), Allen’s Gallinule<br />

(Porphyrio alleni), Caspian Plover(Charadrius asiaticus),<br />

European Cuckoo(Cuculus canorus), Madagascar Lesser<br />

Cuckoo(Cuculus rochii), Cassin’s Spinetail(Neafrapus<br />

cassini), White-bellied Kingfisher(Alcedo leucogaster),<br />

African Dwarf Kingfisher (Ispidina lecontei), Blue-<br />

cheeked Bee-eater (Merops persicus), Eurasian Roller<br />

(Coracias garrulous), Little SpottedWoodpecker<br />

(Campe<strong>the</strong>ra cailliautii), Bearded Woodpecker<br />

(Dendropicos namaquus), Blue Swallow(Hirundo<br />

atrocaerulea), Banded Martin (Riparia cincta), African<br />

Penduline Tit (Anthoscopus caroli), Purple-throated<br />

Cuckoo-Shrike (Campephaga quiscalina), Leaflove<br />

(Pyrrhurus scandens), Isabelline Wheatear (Oenan<strong>the</strong><br />

isabellina), Black-capped Apalis (Apalis nigriceps),<br />

White-winged Warbler (Bradypterus carpalis), Carru<strong>the</strong>rs’<br />

Cisticola (Cisticola carru<strong>the</strong>rsi), Stout Cisticola (Cisticola<br />

robustus), Trilling Cisticola(Cisticola woosnami), Grey<br />

Longbill (Macrosphenus concolor), Yellow Longbill<br />

(Macrosphenus flavicans), Tit Hylia (Pholidornis rushiae),<br />

Wood Warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix), Blue-headed<br />

Crested Flycatcher (Trochocercus nitens), Plain-backed<br />

Pipit(Anthus leucophrys), Papyrus Gonolek (Laniarius<br />

mufumbiri), Woodchat Shrike(Lanius senator),<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 9

Wattled Starling(Creatophora cinerea), Red-chested<br />

Sunbird(Cinnyris erythrocerca)<br />

2.5. MAMMALS<br />

A total <strong>of</strong> fifty (50) large and small mammal species<br />

are known to occur in Mabira Forest Reserve. A high<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species list are forest-dependent,<br />

and includes Deomys ferrugineus and Scutisorex<br />

somereni, closed forest-dependent specalists <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

regarded as two <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most sensitive indicators <strong>of</strong> forest<br />

disturbance. The <strong>Uganda</strong>n endemic shrew Crocidura<br />

selina, only previously recorded from Mabira Forest<br />

(Nicoll and Rathbun, 1990) has not been recorded since<br />

but has been recorded in o<strong>the</strong>r forests. Species with high<br />

conservation value include Crocidura maurisca and<br />

Casinycteris argynnis – a new record for Mabira forest.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>rs protected under <strong>the</strong> CITES include Red-tailed<br />

Monkey (Cercopi<strong>the</strong>cus ascanius), Potto (Perodictictus<br />

potto), Galago (Galago senegalensis), Leopard (Pan<strong>the</strong>ra<br />

pardus), Grey Cheeked Mangabey (Cercocebus abigena)<br />

and Baboons (Papio anubis).<br />

2.6. AMPHIBIANS<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> common amphibian species are associated<br />

with permanent wetlands, rivers or water points. Species<br />

<strong>of</strong> genera Afrana, Hyperolius, Xenopus, Hoplobatrachus<br />

and Afrixalus seem to select habitats with water all year<br />

round. The commonest species were members <strong>of</strong> family<br />

Hyperoliidae. Members <strong>of</strong> family Ranidae were also<br />

found to be common.<br />

The most common species <strong>of</strong> family Hyperoliidae<br />

are generally associated with permanent water<br />

sources. Members <strong>of</strong> genera Xenopus, Afrana and<br />

Hoplobatrachus were also quite common. Members <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se genera are commonly found near water, more so<br />

for <strong>the</strong> bullfrog, which only gets out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> water to feed.<br />

Afrana angolensis is a riverine species found mainly<br />

along rivers and this was encountered along rivers in<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve (Table A4). One member <strong>of</strong> family<br />

Arthroleptidae, Artholeptis adolfifriederici is a new<br />

record for Mabira Forest Reserve.<br />

10<br />

2.7. REPTILES<br />

Mabira Central Forest Reserve has a variety <strong>of</strong> reptiles.<br />

More than 23 species <strong>of</strong> reptiles have been identified in<br />

<strong>the</strong> reserve. Reptiles are highly mobile and live in a range<br />

<strong>of</strong> habitats. They may be encountered in aquatic, bush,<br />

forest, rocky or riverine terrain. The tolerance <strong>of</strong> reptiles<br />

to a range <strong>of</strong> habitat types explains <strong>the</strong> large diversity<br />

<strong>of</strong> reptile species in <strong>the</strong> forest reserve.The key reptiles<br />

in <strong>the</strong> reserve however, include chameleons, geckos,<br />

forest and nile monitor lizards, skinks, snakes including<br />

tree and house snakes, pythons, cobras, mambas, puff<br />

adders and vipers. A list <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> key reptile species in<br />

<strong>the</strong> forest reserve toge<strong>the</strong>r with an indication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

respective conservation status is included in Table A5 in<br />

<strong>the</strong> annex.<br />

2.8. BUTTERFLIES<br />

A total <strong>of</strong> 199 species <strong>of</strong> butterflies is known to occur<br />

in Mabira forest. Nine (9) Papilioidae, twenty four (24)<br />

Pieridae, twenty five (25) Lycaenidae, one hundred<br />

and twenty eight (128) Nymphalidae aud thirteen (13)<br />

Hesperiidae. A relatively high proportion (73 percent) <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> total were forest-dependent butterflies. Details <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> species taken from each family, and each<br />

subfamily in <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Papilionidae, Pieridae and<br />

Nymphalidae, are provided in Table 2.<br />

It can be seen that <strong>the</strong> reserve supports at least 16 percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>’s Rhopaloceran fauna, including 24 percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country’s Pieridae, 29 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Nymphalidae<br />

and 38 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> subfamily Charaxinae (Howard<br />

& Davenport, 1996). Of <strong>the</strong> species registered, those<br />

<strong>of</strong> particular interest included Sallya natalensis a new<br />

record for <strong>Uganda</strong> (Howard & Davenport, 1996). This<br />

butterfly is a migratory insect so unusual distribution<br />

records are not too surprising, however, its previous<br />

known range was from Natal to parts <strong>of</strong> Kenya (Larsen,<br />

1991). Charaxes boueti, meanwhile, a member <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> more commonly studied subfamilies, represents a<br />

new record for this forest (Howard & Davenport, 1996):<br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> few areas in <strong>the</strong> country which have been<br />

comparatively well investigated for <strong>the</strong>ir Rhopaloceran<br />

fauna.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

At least two sub-species endemic to <strong>Uganda</strong> were<br />

registered, Tanue<strong>the</strong>ira timon orientius; <strong>Uganda</strong>n<br />

forests being <strong>the</strong> eastern limit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species’ range and<br />

Acraea lycoa entebbia, known only from central and<br />

eastern <strong>Uganda</strong>. Acraea agan ice ugandae, meanwhile,<br />

an uncommon butterfly is restricted to <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

shoreline <strong>of</strong> Lake Victoria (Howard & Davenport, 1996).<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r species <strong>of</strong> limited range include <strong>the</strong> skipper<br />

Ceratrichia mabirensis (Mabira being <strong>the</strong> Type Locality)<br />

with a patchy distribution, limited to parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>Uganda</strong>,<br />

Tanzania and western Kenya (Larsen, 1991), and<br />

Pseudathyma plutonica a scarce insect ranging from<br />

eastern Democratic Republic <strong>of</strong> Congo (DRC) to western<br />

Kenya. Moreover, Fseudacraea clarki, a comparatively<br />

large and conspicuous butterfly has records from<br />

Cameroon to Gabon and West Kenya, although Larsen<br />

(1991) maintains its absence from <strong>the</strong> latter. It is certainly<br />

not a common insect in East Africa.<br />

Mabira Forest Reserve may be considered rich in terms<br />

<strong>of</strong> its butterfly fauna, supporting a high percentage <strong>of</strong><br />

forest-dependent butterflies, as well as a number <strong>of</strong><br />

uncommon and restricted-range species (Howard &<br />

Davenport, 1996). Despite a recent history <strong>of</strong> intensive<br />

human disturbance in this forest (as reflected by <strong>the</strong><br />

fact that almost a quarter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> species recorded are<br />

associated with forest edge and woodland habitats), <strong>the</strong><br />

butterfly fauna has shown marked resilience (Howard &<br />

Davenport, 1996). Two species <strong>of</strong> Nymphalidae Acraea<br />

rogersi and Bicyclus mesogena, both reliant on dense,<br />

undisturbed forest demonstrate <strong>the</strong> environmental<br />

flexibility <strong>of</strong> some invertebrate communities (Howard &<br />

Davenport, 1996).<br />

Table 2: Species numbers recorded in Mabira from each family and from Papilionidae, Pieridae and<br />

Nymphalidae subfamilies<br />

Family <strong>Uganda</strong> Forest % <strong>Uganda</strong><br />

Subfamily Total Total Total<br />

Papilionidae 31 9 29<br />

Papilioninae 31 9 29<br />

Pieridae 100 24 24<br />

Coliadinae 10 3 30<br />

Pierinae 90 21 23<br />

Lycaenidae 460 25 5<br />

Nymphalidae 447 128 29<br />

Danainae 13 7 54<br />

Satyrinae 71 20 28<br />

Charaxinae 65 25 38<br />

Apaturinae 1 1 100<br />

Nymphalinae 195 50 26<br />

Acraeinae 101 24 24<br />

Liby<strong>the</strong>inae 1 1 100<br />

Hesperiidae 207 13 6<br />

TOTAL 1245 199 16<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011 11

Restricted-range butterflies recorded from Mabira<br />

include Belenois victoria Victoria White, Dixeia charina<br />

African Small White, Epitola catuna, Lachnocnema<br />

bibulus Woolly Legs, Tanue<strong>the</strong>ira timon, Cacyreus<br />

audeoudi Audeoud’s Bush Blue, Amauris hecate Dusky<br />

Danaid, Charaxes port hos, Charaxes pythodoris Powder<br />

Blue Charaxes, Palla ussheri, Apaturopsis clenchares<br />

Painted Empress, Euryphura albimargo, Euryphura<br />

chalcis, Pseudathyma plutonica, Pseudacraea clarki,<br />

12<br />

Neptis trigonophora, Sallya natalensis Natal Tree<br />

Nymph, Hypolimnas dubius Variable Diadem, Acraea<br />

aganice Wanderer, Acraea rogersi Rogers’ Acraea,<br />

Acraea semivitrea, Acraea tellus, Celaenorrhinus bettoni,<br />

Celaenorrhinus proxima, Gomalia elma African Mallow<br />

Skipper, Ceratrichia mabirensis, and Caenides dacena.<br />

The list <strong>of</strong> known butterflies <strong>of</strong> Mabira forest are given<br />

in Table A6.<br />

The Economic Valuation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proposed Degazettement <strong>of</strong> Mabira CFR | 2011

3.0. ECONOMIC EVALUATION OF THE<br />

SUGAR SECTOR IN UGANDA<br />

3.1. GLOBAL SUGAR PRODUCTION<br />

TRENDS<br />

More than 130 countries produce sugar world wide. Of<br />

<strong>the</strong>se, 66 percent process <strong>the</strong>ir sugar from sugarcane.<br />

The rest produce sugar from sugar beet. Sugarcane<br />

primarily grows in <strong>the</strong> tropical and sub-tropical zones<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn hemisphere, while sugar beet is<br />

largely grown in <strong>the</strong> temperate zones <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

hemisphere (ED&F Man, 2004). Prior to 1990, about 40<br />

percent <strong>of</strong> sugar was made from beet but sugarcane<br />

production has grown more rapidly over <strong>the</strong> last two<br />

decades because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lower costs associated with its<br />

production.<br />

The top seven sugar producing countries in <strong>the</strong> world<br />

include Brazil, India, <strong>the</strong> European Union, China,<br />

Thailand, South Africa and Mauritius. The above seven<br />

countries produce up to sixty (60) percent <strong>of</strong> total global<br />

output (USDA, 2006). Projections indicate increased<br />

sugar production in 2006/07 due to higher production<br />

in Brazil, India, China and Thailand. Production in <strong>the</strong><br />

EU was expected to decline by 5 million tonnes, from<br />

21.8 million metric tonnes to 16.8 million metric tonnes<br />

(USDA, 2007).<br />

Over seventy (70) percent <strong>of</strong> global sugar production<br />

is consumed in <strong>the</strong> country <strong>of</strong> origin, implying that<br />

only thirty (30) percent is traded in <strong>the</strong> world sugar<br />

market (ED&F Man, 2004). As indicated in Table 3, world<br />

consumption <strong>of</strong> sugar was higher than production for<br />

2005 and 2006 (Table 3). Africa, Asia, Greater Europe<br />

(outside EU) and North America were <strong>the</strong> regions<br />

with <strong>the</strong> largest sugar deficit (Table 3). In Africa, <strong>the</strong><br />

deficit was 2.8 and 2.7 million tonnes in 2005 and 2006<br />

respectively (FAO, 2006). More than 60 percent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

global consumption <strong>of</strong> sugar takes place in developing<br />

countries, with China and India leading <strong>the</strong> way. In<br />

addition, it is <strong>the</strong> developing countries particularly in<br />