Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report - Biodiversity Foundation for Africa

Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report - Biodiversity Foundation for Africa

Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report - Biodiversity Foundation for Africa

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

MIOMBO ECOREGION<br />

VISION REPORT<br />

Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo<br />

December 2001 (published 2011)<br />

Occasional Publications in <strong>Biodiversity</strong> No. 20

WWF - SARPO<br />

MIOMBO ECOREGION<br />

VISION REPORT<br />

2001<br />

(revised August 2011)<br />

by<br />

Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo<br />

Occasional Publications in <strong>Biodiversity</strong> No. 20<br />

<strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Africa</strong><br />

P.O. Box FM730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

PREFACE<br />

The <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Vision</strong> <strong>Report</strong> was commissioned in 2001 by the Southern <strong>Africa</strong><br />

Regional Programme Office of the World Wide Fund <strong>for</strong> Nature (WWF SARPO). It<br />

represented the culmination of an ecoregion reconnaissance process led by Bruce Byers (see<br />

Byers 2001a, 2001b), followed by an ecoregion-scale mapping process of taxa and areas of<br />

interest or importance <strong>for</strong> various ecological and bio-physical parameters. The report was then<br />

used as a basis <strong>for</strong> more detailed discussions during a series of national workshops held across<br />

the region in the early part of 2002. The main purpose of the reconnaissance and visioning<br />

process was to initially outline the bio-physical extent and properties of the so-called <strong>Miombo</strong><br />

<strong>Ecoregion</strong> (in practice, a collection of smaller previously described ecoregions), to identify<br />

the main areas of potential conservation interest and to identify appropriate activities and<br />

areas <strong>for</strong> conservation action.<br />

The outline and some features of the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> (later termed the <strong>Miombo</strong>–<br />

Mopane <strong>Ecoregion</strong> by Conservation International, or the <strong>Miombo</strong>–Mopane Woodlands and<br />

Grasslands) are often mentioned (e.g. Burgess et al. 2004). However, apart from two booklets<br />

(WWF SARPO 2001, 2003), few details or justifications are publically available, although a<br />

modified outline can be found in Frost, Timberlake & Chidumayo (2002).<br />

Over the years numerous requests have been made to use and refer to the original<br />

document and maps, which had only very restricted distribution. Now, 10 years after the<br />

original draft <strong>Vision</strong> <strong>Report</strong> was produced, we are making the report more widely available as<br />

a <strong>Biodiversity</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Africa</strong> (BFA) publication. Only minor corrections or additions<br />

have been made to the original document, and maps from other publications have been added<br />

in.<br />

Another BFA Publication (No. 21, Timberlake et al. 2011) presents a series of maps<br />

showing the areas of biological importance, an output from a BFA consultancy.<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

We would like to acknowledge the support of WWF SARPO in Harare, particularly Fortune<br />

Shonhiwa, Programme Office <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> visioning process. The maps were<br />

mostly produced by WWF's GIS Unit.

LIST OF CONTENTS<br />

page<br />

PREFACE .................................................................................................................................. 2<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... 2<br />

LIST OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................... 3<br />

1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 5<br />

1.1 <strong>Ecoregion</strong> Conservation ................................................................................................ 5<br />

1.2 The <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> ................................................................................................ 6<br />

1.3 The <strong>Ecoregion</strong> Conservation Planning Process ............................................................ 8<br />

1.4 <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Vision</strong> <strong>Report</strong> ................................................................................ 8<br />

2. PHYSICAL FEATURES AND PROCESSES ..................................................................... 9<br />

2.1 Extent and Physical Determinants................................................................................. 9<br />

2.2 Geology ......................................................................................................................... 9<br />

2.3 Landscape Evolution................................................................................................... 13<br />

2.4 Hydrological Processes ............................................................................................... 14<br />

2.4.1 Rainfall Processes ......................................................................................... 14<br />

2.4.2 Characteristics of the Plateau Surface.......................................................... 14<br />

2.4.3 Spatial Distribution of Surface Water .......................................................... 15<br />

2.4.4 Soil–Water Processes ................................................................................... 15<br />

2.5 Biophysical Processes ................................................................................................. 16<br />

3. BIOLOGICAL FEATURES AND SPECIES..................................................................... 18<br />

3.1 <strong>Ecoregion</strong> Boundary.................................................................................................... 18<br />

3.1.1 Inclusions and Exclusions ............................................................................ 18<br />

3.2 Vegetation Types......................................................................................................... 20<br />

3.3 Species......................................................................................................................... 23<br />

3.3.1 Plants ............................................................................................................ 23<br />

3.3.2 Mammals...................................................................................................... 23<br />

3.3.3 Birds ............................................................................................................. 25<br />

3.3.4 Reptiles / Amphibians .................................................................................. 25<br />

3.3.5 Fish............................................................................................................... 26<br />

3.3.6 Invertebrates................................................................................................. 26<br />

3.4 Areas of Evolutionary Significance ............................................................................ 28<br />

3.5 Areas Important <strong>for</strong> Animal Movement and Migration.............................................. 28<br />

4. ECOLOGICAL DETERMINANTS AND PROCESSES................................................... 30<br />

4.1 Ecological Determinants ............................................................................................. 30<br />

4.2 Biophysical Processes ................................................................................................. 30<br />

4.3 Plant Biomass and Herbivory...................................................................................... 31<br />

4.4 Carbon Storage and Sequestration .............................................................................. 31<br />

4.5 Nutrient Cycling.......................................................................................................... 32<br />

4.6 Fire .............................................................................................................................. 32<br />

4.7 Human Interactions ..................................................................................................... 33<br />

5. SOCIO-ECONOMIC FEATURES AND PROCESSES .................................................... 34<br />

5.1 Socio-Economic Context............................................................................................. 34

5.2 Key Socio-Economic Features and Processes............................................................. 34<br />

5.2.1 Socio-Political Factors .................................................................................. 34<br />

5.2.3 Cultural Processes ........................................................................................ 35<br />

5.2.4 Land Use and Socio-Economic Development ............................................. 35<br />

5.3 Economic and Policy Environment............................................................................. 39<br />

5.3.1 Socio-economic Threats and Opportunities ................................................. 39<br />

5.3.2 Cross-cutting Factors.................................................................................... 40<br />

5.3.3 Threats.......................................................................................................... 40<br />

5.3.4 Opportunities................................................................................................ 42<br />

6. CONSERVATION VISION AND AREAS OF BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE............. 44<br />

6.1 <strong>Vision</strong> Statement ......................................................................................................... 44<br />

6.1.1 Rationale........................................................................................................ 44<br />

6.2 Areas of Importance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Biodiversity</strong> Conservation ................................................... 45<br />

7. BIBLIOGRAPHY AND REFERENCES ........................................................................... 64<br />

Appendix 1. List of endemic or near-endemic vertebrate taxa in the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong>. ..... 69<br />

Appendix 2. <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> habitats ................................................................................ 77<br />

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES<br />

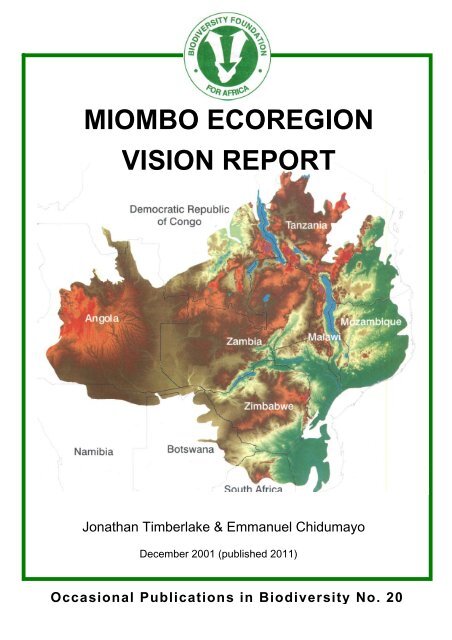

Figure 1. The <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> and southern <strong>Africa</strong> ........................................................... 7<br />

Figure 2. Southern <strong>Africa</strong> – physiography and altitude .......................................................... 10<br />

Figure 3. <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> – rainfall................................................................................... 12<br />

Figure 4. <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> – vegetation types .................................................................... 19<br />

Figure 5. <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> – protected areas ...................................................................... 38<br />

Figure 6. <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> – areas of biological importance.............................................. 47<br />

Figure 7. <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> – areas of significance <strong>for</strong> habitat conservation ...................... 79<br />

Table 1. Revised <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> vegetation units ........................................................... 20<br />

Table 2. Numbers of species recorded from the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong>. .................................... 27<br />

Table 3. Protected areas within the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> ......................................................... 38<br />

Table 4. Identified areas of importance <strong>for</strong> conservation in the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> ............. 46

1. INTRODUCTION<br />

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 5<br />

The mission of the World Wide Fund <strong>for</strong> Nature (WWF) is the conservation of nature and the<br />

promotion of sustainable use of natural resources. Historically, the strategy of WWF was largely<br />

based on single species, often driven by the need to respond to dramatic poaching levels of wellknown<br />

animal species and to address severe cases of habitat degradation and loss all over the<br />

world. While these campaigns were entirely legitimate, they may have inadvertently underemphasized<br />

some fundamental conservation imperatives such as conservation of large-scale<br />

ecological processes, maintaining viable populations of species, addressing habitat<br />

representativeness and ecosystem diversity. After reviewing the present challenges and lessons of<br />

conservation projects over the last 50 years, WWF International has decided that an ecoregion<br />

approach is the most appropriate to set conservation targets and priorities at a continental or<br />

worldwide level. This culminated in the determination of ecoregions across the world (Olson et<br />

al. 2001), with around 120 in <strong>Africa</strong>, and the selection of the Global 200 most important<br />

ecoregions (WWF 1999).<br />

As part of this approach, the WWF Southern <strong>Africa</strong> Regional Programme Office (WWF-<br />

SARPO) has embarked on an ecoregion conservation programme <strong>for</strong> the <strong>Miombo</strong> (or Southern<br />

Caesalpinoid Woodlands) <strong>Ecoregion</strong>. This is one of the Global 200 ecoregions, the largest of 21<br />

on mainland sub-Saharan <strong>Africa</strong>. The ecoregion provides a good example in which management<br />

of hydrological processes is central to maintaining its essential features, such as soil moisture<br />

regimes, dominant vegetation cover, characteristic species and associated evolutionary processes.<br />

In this regard, the sustainable management of water, involving the wise use of ubiquitous dambos<br />

(broad, seasonally-inundated drainage lines on the plateau) and the protection of major river<br />

catchments located in the deep aeolian Kalahari sands of Angola and Zambia, is crucial to<br />

ecological functioning. The goal of this programme is to contribute to the maintenance of<br />

biodiversity and functioning ecosystems in the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>for</strong> the benefit of people and<br />

nature, while the purpose is to extend that part of the ecoregion where biodiversity conservation<br />

and functioning ecosystems are fully incorporated into landuse practices, to the benefit of<br />

conservation of both agricultural lands and wildlands.<br />

1.1 <strong>Ecoregion</strong> Conservation<br />

<strong>Ecoregion</strong> conservation enables WWF to take a more comprehensive approach to biodiversity<br />

conservation without sacrificing sensitivity to local biodiversity issues and socio-economic<br />

conditions. This larger-scale, more integrated approach enables WWF to better assess both the<br />

proximate and root causes of biodiversity loss, and to design policy and management initiatives<br />

at appropriate levels from international trade policies to site-specific protected area management<br />

or community development projects. Moreover, it allows WWF to connect what it does at the<br />

local level with what needs to be done at national and international levels, to better link field<br />

work with policy work, and to build new partnerships in carrying this out.<br />

An ecoregion is defined as a relatively large unit of land or water that is biologically distinct<br />

from its neighbours, an area that harbours a characteristic set of species, communities, dynamics<br />

and environmental conditions. It embodies the general principles of ecosystem conservation and<br />

the major goals of conservation biology since it encompasses: (a) the representation of all<br />

broadly distinct broad communities and species assemblages, (b) the maintenance of viable plant<br />

and animal populations within large expanses of intact habitat, (c) special recognition of keystone<br />

ecosystems, habitats, species and phenomena, (d) conservation of large scale ecological

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 6<br />

processes, and (e) conservation of species of special concern. It differs from other approaches in<br />

that it demands a visionary and strategic view in planning to conservation, it operates over large<br />

temporal and bio-geographical scales, and it requires an understanding of social and biological<br />

processes and dynamics operating at these scales. It is usually viewed in the long-term context of<br />

50 years. The broad spatial and temporal scale adopted requires an integrated and multidisciplinary<br />

approach where biological units are the basis <strong>for</strong> planning and activities. As an<br />

ecoregion unit may cross political boundaries, thinking must extend beyond national boundaries<br />

or programmes, even though requisite conservation actions happen nationally. The challenge is<br />

there<strong>for</strong>e to operate over these large spatial scales through coordinated and concerted actions<br />

across political boundaries. Although with many attendant difficulties, the often cross-boundary<br />

nature of the approach is vital to achieving long-term ecosystem conservation goals.<br />

1.2 The <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong><br />

The <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong>, covering over 3.6 million square kilometres across 11 countries of<br />

southern <strong>Africa</strong> (Figure 1), comprises dry and moist woodlands that support some of the most<br />

important thriving large mammal populations left in <strong>Africa</strong>. Black rhinoceros, <strong>Africa</strong>n elephant,<br />

<strong>Africa</strong>n hunting dog, Cheetah and the Slender-nosed crocodile are some of the threatened<br />

species, along with many less-known species of plant, birds, reptiles, fish and insects. More than<br />

half of the estimated 8,500 plant species in this ecoregion are found nowhere else on Earth. There<br />

is also a distinctive bird, reptile and amphibian fauna.<br />

One of the region's main characteristics is the presence of large expanses of rolling savanna<br />

woodland on a gently undulating plain, interspersed with grassy drainage lines (dambos) in a<br />

regular catenary sequence. The pattern is distinct and repetitive. It is the juxtaposition of different<br />

vegetation types – nutrient poor and nutrient-rich woodland, areas of short nutritive grasses<br />

interspersed with taller rank grass, wetlands in an otherwise dry environment – that allows many<br />

of the large herbivores to survive. The herbivores move through the landscape seasonally,<br />

making the best use of <strong>for</strong>age resources in what is generally a nutrient-deficient and low<br />

carrying-capacity environment. In many respects, conservation of these woodlands needs to<br />

focus on broad landscape-level processes and hydrology rather than on specific habitats or<br />

species.<br />

The ecoregion is typified by a dominance of deciduous woodland composed of broad-leaved<br />

trees of the legume subfamily Caesalpinioideae. Owing to the deciduous nature of the woodland<br />

there is a well-developed grass layer which, in turn, gives rise to frequent and wide-spreading<br />

fires. Caesalpinoid woodlands are confined to the gently undulating, unrejuvenated Central<br />

<strong>Africa</strong>n plateau at an altitude of 800–1200 m, although they come down to the coastal plain in<br />

Mozambique and Tanzania. The ecoregion is incised by the large river valleys of the Zambezi,<br />

Luangwa and Limpopo, and by the Rift Valley lakes of Tanganyika and Malawi. A number of<br />

major drainage basins such as the Zambezi, Limpopo, Save, Cuando, Kavango, Rufiji, Rovuma<br />

and Luapula (part of the Upper Congo) are incorporated.<br />

Although the ecoregion is commonly termed the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong>, this is confusing as the<br />

Caesalpinoid woodlands which it comprises extend significantly beyond true miombo woodland.<br />

A unimodal rainfall pattern with distinct and prolonged dry seasons, coupled with the generally<br />

leached and impoverished soils, are major features. It is the combination of environmental<br />

factors– rainfall, length of dry period, soil nutrient status and fire – which is the probable main<br />

determinant of woodland limits and separates this from adjacent ecoregions.

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 7<br />

Figure 1. The <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> and southern <strong>Africa</strong> (from WWF SARPO 2003).<br />

The primary and direct impacts on the ecoregion come from the large and rapidly growing<br />

human population and its demand <strong>for</strong> agricultural land. Large areas of dry woodland, unlike<br />

moist <strong>for</strong>ests, can be more easily converted to agricultural land owing to the lower above-ground<br />

woody plant biomass, though the social and environmental consequences are probably as<br />

profound as with moist <strong>for</strong>est.<br />

Most of the miombo savanna woodlands are inhabited, and there are few areas that can be<br />

considered at all pristine. Many rural people depend heavily on natural resources <strong>for</strong> their<br />

livelihoods. These conditions have led to a strong emphasis on the sustainable use of natural<br />

resources in the region, and on Community-based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM)<br />

programmes. The region is considered by many to be a global model <strong>for</strong> CBNRM. As other<br />

organisations besides WWF are involved in natural resources management and conservation<br />

initiatives within the ecoregion, WWF's planning process will require collaboration with a range<br />

of partners.<br />

The <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> is exceptionally large compared to many others, and also diverse.<br />

Although it can be split into a number of sub-regions (<strong>for</strong> example, Burgess et al. 2004), it was<br />

felt that its integrity should be retained, as it is this that gives rise to its uniqueness and<br />

importance. In some ways it could be said that conservation of the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> is more<br />

about conservation of processes operating at a landscape scale across thousands of square<br />

kilometres than about conservation of species or individual habitats.

1.3 The <strong>Ecoregion</strong> Conservation Planning Process<br />

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 8<br />

The first step in the ecoregion conservation planning process is a reconnaissance to outline the<br />

current state of biological and socio-economic knowledge <strong>for</strong> the area and to identify major gaps.<br />

This stage involves a certain amount of data gathering and assessment. The reconnaissance also<br />

seeks to identify major factors influencing environmental change and loss of biodiversity, to<br />

identify key problems and opportunities <strong>for</strong> conservation interventions, and to provide a basis on<br />

which to plan a more comprehensive biological and socio-economic assessment.<br />

Both the reconnaissance and subsequent assessments provide the basis <strong>for</strong> developing a<br />

biodiversity conservation vision. The vision should set out long-term goals <strong>for</strong> conservation of<br />

the ecoregion's biodiversity, identify key sites, populations and ecological processes. It should<br />

guide the development of the action plan and any strategic decisions as circumstances and<br />

opportunities change. This is followed up by the development of a conservation action plan.<br />

The action plan sets the 10 to 15 year goals <strong>for</strong> conservation of the ecoregion's biodiversity, and<br />

identifies the actions needed to achieve those goals. It is a comprehensive blueprint <strong>for</strong><br />

conservation action, and identifies the first steps on the road to achieving the vision.<br />

1.4 <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Vision</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

This report has built upon the reconnaissance process and vision building workshop to produce a<br />

biodiversity vision. This vision is essentially a statement coupled with a series of biologically<br />

important areas that have been identified <strong>for</strong> special attention. These areas have been identified<br />

and mapped, and are described in this report. The expectation is that if we concentrate our<br />

conservation ef<strong>for</strong>ts on them with full recognition of the goals of biodiversity conservation, we<br />

should eventually realize our long-term biodiversity vision.<br />

The <strong>Vision</strong> <strong>Report</strong> is a further step in the ecoregion planning process. It has built upon the<br />

reconnaissance process but has advanced by producing a set of biologically important areas<br />

across the ecoregion in a participatory process that involved biologists and socio-economic<br />

experts. These areas represent overlaps in the occurrence and distribution of key taxa, species and<br />

genera and in some cases, ecological processes. Boundaries of some of these areas are still<br />

tentative, hence further refinement and detailed biological and associated socio-economic<br />

assessments will be needed, along with identification of opportunities <strong>for</strong> conservation.<br />

The major ecological processes identified during the reconnaissance and vision workshops have<br />

also been described, as are the major socio-economic opportunities and threats. It is worth stating<br />

that in this process an attempt was made to map out socio-economic processes, which will need<br />

to be seriously considered in the construction of conservation action plans.<br />

The report sets out to give an overview of the Caesalpinoid Woodland (<strong>Miombo</strong>) <strong>Ecoregion</strong>, and<br />

to describe its boundaries, biological and socio-economic attributes. Particular attention has been<br />

given to species diversity, regional endemism, global significance and to the ecological processes<br />

that both underpin and unify the ecoregion. Suggestions <strong>for</strong> further necessary short-term<br />

activities are also described.

2. PHYSICAL FEATURES AND PROCESSES<br />

2.1 Extent and Physical Determinants<br />

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 9<br />

The <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> covers over 3.8 million km 2 in central and southern <strong>Africa</strong>, extending<br />

from the west coast in Angola to the east coast in Mozambique and Tanzania. It includes all or<br />

part of 11 countries – Angola, Namibia, Botswana, South <strong>Africa</strong>, Zimbabwe, Zambia,<br />

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Mozambique, Malawi, Tanzania and Burundi. Much of<br />

the ecoregion is on the ancient <strong>Africa</strong>n plateau with an altitude of 800 to 1250 m above sea level,<br />

but in the east the ecoregion transcends the escarpment and elements of the ecoregion can be<br />

found in the east <strong>Africa</strong>n coastal zone, at 200 to 300 m altitude (Figure 2). In spite of the<br />

favourable elevation, the biological elements of the ecoregion give way to other biomes in the<br />

northeast, south and southwest. Elevation there<strong>for</strong>e does not fully determine the <strong>Miombo</strong><br />

<strong>Ecoregion</strong> boundary.<br />

Overall, the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> boundary appears to be determined by the interaction of<br />

topography, precipitation and temperature. Climate is probably the most important determinant.<br />

The ecoregion occurs in the unimodal rainfall zone, except in the northeast in central Tanzania<br />

where rainfall tends to be bimodal. Mean annual rainfall is in the range of 600 to 1400 mm<br />

(Figure 3) and occurs from November to April. To the northwest, the boundary roughly follows<br />

the 1400 mm isohyet while to the northeast and south, the boundary follows the 600 mm isohyet.<br />

It is obvious that the biological elements of the ecoregion are ill-adapted to humid and arid<br />

conditions. In central and southern <strong>Africa</strong> both humid and arid conditions are associated with<br />

mean maximum temperatures higher than 30 o C. Much of the region there<strong>for</strong>e lies in the warm<br />

subhumid zone with a mean maximum temperature of 24–27 o C.<br />

2.2 Geology<br />

The geological foundation of much of south and central <strong>Africa</strong> consists of large, stable, Archaean<br />

crustal blocks called cratons, of relatively low metamorphic grade, separated by broad zones of<br />

more highly metamorphosed rocks known as mobile belts. The cratonic nuclei include the<br />

Congo, Tanzania, Kaapvaal and Zimbabwe cratons; dating indicates a long and complex<br />

geological history and gives ages ranging from around 3500 to 2600 million years (Ma). Cratonic<br />

stabilisation did not occur everywhere at the same time. In the Zimbabwe craton, which is the<br />

best exposed, some early stabilisation had been effected by 3300 Ma with final stabilisation at<br />

about 2600 Ma, accompanying the emplacement of vast volumes of potassium-rich granites.<br />

The cratons now consist of the de<strong>for</strong>med remains of volcano-sedimentary piles (greenstone belts)<br />

intruded by various, and numerous, granites. Metamorphic grade in the greenstone belts is such<br />

that primary textures and structures are often well preserved and the primary nature of the rocks<br />

is clear. For example, basaltic lavas dominate the volcanic pile and numerous examples of<br />

pillows indicate that eruption occurred under water. Also pockets of limestone, although now<br />

recrystallised, show fossil stromatolites in places indicating that, here at least, water depths were<br />

shallow. Typically, the basaltic greenstones weather to give fertile, reddish soils. Prominent<br />

among the associated chemical sediments are banded iron <strong>for</strong>mations and ferruginous cherts,<br />

which often outcrop as prominent well-wooded ridges.

Figure 2. Southern <strong>Africa</strong> – physiography and altitude.<br />

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 10

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 11<br />

The mobile belts range from late Archaean to early Palaeozoic, with age groupings around 2700<br />

Ma, 2000–1800 Ma, 1400–1100 Ma and 950–450 Ma. In places they show evidence of<br />

metamorphism and de<strong>for</strong>mation of more than one age. Rocks include granitic gneisses,<br />

metasediments and metavolcanics all at high metamorphic grade. Perhaps the oldest of these, the<br />

well-documented but still enigmatic Limpopo Belt, separates the Zambezi craton from the<br />

Kaapvaal craton to the south. It consists of a central zone of Archaean metasediments, with a<br />

major development of quartzites, flanked to the north and south by high grade rocks of the<br />

adjacent cratons. Metamorphism and tectonism is late Archaean, at around 2700 Ma, followed by<br />

a second, early Proterozoic, phase at 2000 Ma.<br />

Emplaced at 2580 Ma, and af<strong>for</strong>ding a magnificent marker <strong>for</strong> the end of the Archaean and the<br />

beginning of the Proterozoic, is the Great Dyke of Zimbabwe. Funnel-shaped in cross-section in<br />

its present erosion plane, it is not a true dyke but a NNE-trending line of contiguous, elongate,<br />

mafic/ultramafic, layered intrusions that almost bisects the craton. Gabbroic rocks <strong>for</strong>m the upper<br />

part and ultramafic rocks, mainly pyroxenite and dunite, the major and lower part of the layered<br />

sequences. Weathering of the dunite has produced a surface serpentisation and nickel-rich soils<br />

that characteristically support unique, nickel-tolerant vegetation.<br />

Proterozoic sedimentary and volcanic rocks of various ages occur intermittently overlying the<br />

Archaean cratons. Most of these extend into the marginal Proterozoic mobile belts to become<br />

highly de<strong>for</strong>med and metamorphosed; in places they have also been thrust over the adjacent<br />

cratons during the de<strong>for</strong>mation. Among these is the early Proterozoic Magondi Supergroup of<br />

basalts, quartzites, dolomitic marbles and metapelites, deposited on the NW side of the<br />

Zimbabwe craton. Orogeny around 2000–1800 Ma produced the Magondi Mobile Belt, involving<br />

the de<strong>for</strong>mation of the Magondi rocks and underlying basement. On a larger scale, this is part of<br />

more widespread orogenic events affecting southern, central and eastern <strong>Africa</strong> at this time. On<br />

the northern flank of the Zimbabwe craton, the various metasediments and infolded basement of<br />

the Zambezi Belt were extensively de<strong>for</strong>med around 850 Ma. The belt cuts across the earlier<br />

Magondi Belt and extends west into southern and central Zambia to the Copperbelt. Eastwards it<br />

links with the N-trending Mozambique Mobile Belt, which straddles Zimbabwe's eastern<br />

international border with Mozambique and extends northwards as a major structural zone into<br />

Zambia, Tanzania and Uganda. In eastern Zimbabwe, the late Proterozoic Umkondo Group<br />

<strong>for</strong>ms a cratonic cover of quartzites, shale and minor volcanics, and extends eastwards to become<br />

an integral part of the Mozambique Belt.<br />

Cratonic granite-greenstone terrains, mobile belts and cratonic cover rocks together <strong>for</strong>m the<br />

Precambrian Basement plat<strong>for</strong>m on which the Phanerozoic rocks were deposited. This basement<br />

is host to economically important minerals – gold in the Archaean greenstone belts; chromitite<br />

and platinum group minerals in the Great Dyke; and copper in the Proterozoic, especially in the<br />

Copperbelt of Zambia and Katanga Province of the DRC.<br />

The most conspicuous rocks of Phanerozoic age in south and central <strong>Africa</strong> belong to the Karoo<br />

Supergroup. These were deposited on Gondwanaland from the late Pennsylvanian (Upper<br />

Carboniferous) to Jurassic Periods, a span of some 100 Ma, as this giant continent moved slowly<br />

across the South Pole and thence northwards to straddle the Equator be<strong>for</strong>e splitting to <strong>for</strong>m the<br />

continents that are familiar today. The sequence of sedimentation in the intracontinental basin,<br />

from all the modern component fragments, reflects the steadily changing climate from frigid to<br />

cool temperate to warm temperate to hot desert. Finally, cracks opened across Gondwanaland<br />

and permitted the eruption of the vast numbers of basalt flows that constitute the uppermost part<br />

of the Karoo Supergroup. Thereafter the modern continents moved to their present positions.

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 12<br />

In <strong>Africa</strong>, Karoo rocks can be traced from extensive areas across South <strong>Africa</strong> to Namibia,<br />

Botswana, Zimbabwe (particularly Matabeleland and the Zambezi Valley), Zambia and small<br />

patches in Malawi, Tanzania and Kenya. Lower Karoo rocks, deposited during the glacial and<br />

cool temperatures, are principally shales and sandstones with coal derived from Glossopteris<br />

flora. The basal <strong>for</strong>mation is a tillite, which commonly rests on a glaciated pavement – the Pre-<br />

Karoo erosion surface.<br />

Figure 3. <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> – rainfall.<br />

Upper Karoo sediments are lighter-coloured grits, sandstones, shales and mudstones that contain<br />

Permian therapsids, Triassic dinosaurs and a variety of plant fossils. Some of the finer grained<br />

rocks are highly erodible, and in certain localities in Hwange National Park, the floor of the<br />

Zambezi Valley and south of Harare exhibit spectacular gully and sheet erosion. The basalts can<br />

be seen today in Lesotho, the Limpopo Valley, Victoria Falls and smaller outliers elsewhere.<br />

The break-up of Gondwanaland produced new coastlines along the eastern and western margins<br />

of <strong>Africa</strong>, and Cretaceous and Cainozoic times are recorded by littoral sediments associated with<br />

shoreline fluctuations. In the hinterland, however, the Kalahari and Congo basins have been the<br />

loci of continental deposition. The most recent deposits are the Kalahari Sands which date from<br />

the Miocene Epoch and which have been blown repeatedly, in various directions, until the<br />

present day. Deposits of these sands now occur far beyond the present Kalahari region, in<br />

scattered patches through Zimbabwe and Zambia, and locally provide the uppermost soil <strong>for</strong> the<br />

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong>. The underlying geology of the ecoregion covers a wide spectrum of rock

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 13<br />

types ranging in age from Archaean onwards but, in itself, does not control the distribution of the<br />

Caesalpinoid woodlands.<br />

2.3 Landscape Evolution<br />

The landscapes in the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> are dependent mainly on the geology, climate and<br />

drainage, and usually have taken many millions of years to reach the present-day stage.<br />

The geological control is effected by the relevant resistance to weathering that the different rock<br />

types exhibit. Thus more resistant rocks, such as sandstones, quartzites and ironstone <strong>for</strong>mations,<br />

are located along ridges and other high-standing areas, whereas soft rocks, such as shales and<br />

mudstones, occur in low-lying positions. Certain rock types weather to characteristic land<strong>for</strong>ms.<br />

For example, the granite terrain, seen widely across <strong>Africa</strong>, shows curved exfoliated domes<br />

(bornhardts) and rectangularly jointed blocks (tors and inselbergs).<br />

Climate controls both temperature and rainfall, the latter producing the water essential <strong>for</strong><br />

chemical weathering. Much of southern <strong>Africa</strong>, including the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong>, experiences a<br />

marked dry season – wet season climatic regime, which leads to pediplanation as the dominant<br />

geomorphic process.<br />

Drainage governs the movement of water and soil particles to lower levels, ultimately to sea<br />

level. Incision of the river valleys provides the original 'notch' on the ground surface, from which<br />

pediplanation can advance.<br />

Pediplanation entails the retreat of hill slopes as rock is weathered and removed from the steepest<br />

slopes, with resultant advance of the lower pediment and concomitant diminution of the higher<br />

pediment. With the passage of time the areas at the higher level are reduced to become residuals<br />

(inselbergs) while the lower pediments coalesce to <strong>for</strong>m pediplains (erosion surfaces). The<br />

erosion surfaces that can be traced throughout <strong>Africa</strong> south of the Sahara are: Pre-Karoo (300–<br />

200 Ma), Gondwana (170–135 Ma), Post-Gondwana (135–100 Ma), <strong>Africa</strong>n (100–24 Ma), Post-<br />

<strong>Africa</strong>n (24–5 Ma), Pliocene (5–2 Ma) and Quaternary (

2.4 Hydrological Processes<br />

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 14<br />

A large part of the ecoregion is drained by the Zambezi River system that discharges into the<br />

Indian Ocean through Mozambique. Other rivers draining into the Indian Ocean are the Rufiji<br />

and Rovuma in southern Tanzania and Save and Limpopo in Zimbabwe and Mozambique. In the<br />

northwest the ecoregion is drained by the Congo River, the headwaters of which comprise the<br />

Chambeshi–Bangweulu–Luapula system in northern Zambia. The gradient in the headwaters of<br />

the Congo and Zambezi is low and extensive floodplains and swamps occur, such as the Bulozi<br />

floodplain in western Zambia, Bangweulu swamps, Lukanga swamps and Kafue Flats in central<br />

Zambia. The Luangwa is an exception, with its steeper gradient. Consequently there are no<br />

significant swamps along the Luangwa River. The tailwaters of the major rivers draining into the<br />

Indian Ocean have steeper gradients and there<strong>for</strong>e have fewer, if any, expansive wetland areas,<br />

apart from in their deltas which are outside the ecoegion.<br />

The distinctive drainage and hydrological characteristics are determined by three factors: the<br />

seasonal distribution of rainfall, the spatial distribution of surface water and the gradient of the<br />

plateau surfaces.<br />

2.4.1 Rainfall Processes<br />

The three main airstreams affecting the rainy season in the ecoregion are the Congo airstream,<br />

the south-east trades and the northeast monsoons (Davis 1971). The Congo air originates partly<br />

from the southeast trades of the South Atlantic ocean which curve inland over the Congo Basin<br />

as they approach the equator and reach the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> from the northwest. This air<br />

stream is very humid in its lower levels and can produce widespread rain when subjected to<br />

convergence. The south-east trades of the south Indian Ocean hold more moisture during the<br />

summer months (November to April) and bring rains to the northeastern portion of the ecoregion,<br />

especially in Tanzania where rainfall tends to be bimodal. The northeast monsoon originates in<br />

the Asiatic high pressure system and may bring rain to the eastern portion of the ecoregion in<br />

summer.<br />

Most of the rainfall occurs near the margins of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone along the<br />

Congo Air Boundary and at the northern limit of the southeast trades. Consequently, rainfall<br />

decreases from north to south across the ecoregion, except <strong>for</strong> areas at higher altitude and those<br />

in the proximity of lakes and swamps, both of which receive above-average rainfall compared to<br />

the surrounding areas. The rainy season is about 200 days in the north and 100 days in the south<br />

and valleys, such as the mid-Zambezi. However, there are substantial annual variations in the<br />

duration and amount of rainfall.<br />

2.4.2 Characteristics of the Plateau Surface<br />

The gently sloping plateau landscape that characterises the ecoregion has given rise to a sluggish,<br />

very widely-spaced drainage system. Drainage of the low plateau interfluves is probably effected<br />

mainly by sheet flow. Infiltration may account <strong>for</strong> a considerable proportion of the rainfall,<br />

especially in areas of Kalahari sands in the southwestern portion. The characteristic feature of the<br />

drainage in the headwaters of the plateau streams is the broad, shallow linear depressions known<br />

as dambos which may retain water and maintain streamflow well into the dry season. Dambos<br />

cover 10 to 15% of the area in the headwaters of the Zambezi and Congo, and about 5% in the<br />

middle waters of the Zambezi (Byers 2001a). The sluggish drainage has also given rise to

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 15<br />

expansive wetlands in the headwaters of the major rivers that are important habitats <strong>for</strong> wildlife<br />

and fish.<br />

2.4.3 Spatial Distribution of Surface Water<br />

One characteristic feature of rainfall of the ecoregion is its high inter-annual variability. The<br />

coefficient of variation which is a measure of this variability decreases with increase in rainfall.<br />

Thus areas with low rainfall have highly variable rainfall. This coefficient varies from 35% in the<br />

southern parts of Zimbabwe that receive about 400 to 600 mm per year, to 25% along the central<br />

watershed which receives 700 to 900 mm per year. In Zambia the coefficient of variation ranges<br />

from 30% along the mid-Zambezi valley to 15% in the northern high rainfall belt. Most of<br />

Malawi has a coefficient of variation between 20 and 25%.<br />

Because of seasonal rainfall (November–April), peak flow occurs during February in the<br />

headwaters of the major rivers and as late as May in the tailwaters, well after the end of the rainy<br />

season. Most small streams dry up during the dry season while in larger streams flow is a small<br />

fraction of the wet season discharge. As there is virtually no rainfall in the dry season,<br />

streamflow is maintained by baseflow. Rainfall that contributes to streamflow and ground water<br />

recharge decreases from north to south across the ecoregion. Most of the discharge of the main<br />

rivers draining into the Indian Ocean is there<strong>for</strong>e derived from the wetter northern parts and is<br />

crucial to the maintenance of the East <strong>Africa</strong>n Coast <strong>Ecoregion</strong>.<br />

2.4.4 Soil–Water Processes<br />

The plateau soils in the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> are of eluvial origin on basement quartzites, schists<br />

and granitic rocks. They are heavily leached and are poor in nutrients due to low organic matter,<br />

nitrogen and phosphorus content. This has arisen partly because of the poor acidic bedrock from<br />

which these soils are derived and partly due to the long period of weathering and leaching. These<br />

nutrient poor (dystrophic) soils have a low pH and high iron-aluminium toxicity, and range from<br />

sandy loam to sandy clay. As a result of the eluviation process, the clay content in the soil<br />

increases with depth, although most soils are generally shallow with a lateritic horizon. In areas<br />

of active erosion, such as escarpments, the topsoil is continuously removed, thereby exposing the<br />

lateritic material and/or bedrock.<br />

Topsoil (0–30 cm) moisture content varies from 50–70 cm) moisture content remains >10% throughout the year<br />

(Chidumayo 1997). This seasonality in topsoil moisture has implications <strong>for</strong> primary production<br />

by shallow-rooted plants. Plateau soils also show a fertility gradient from the high rainfall areas<br />

with poorer soils in the north to areas with low rainfall and relatively more fertile soils in the<br />

south.<br />

Low-lying areas, such as valleys, are run-on areas and have alluvial soils that are relatively more<br />

fertile (eutrophic). Landscape heterogeneity in the ecoregion has created a gradient in soil<br />

fertility between plateau landscapes and their adjacent valleys. Although low-lying areas receive<br />

less rainfall, this is augmented by run-off from the surrounding escarpments and/or plateaux that<br />

also sustains the alluviation process. Soil moisture regimes and fertility status are thus more<br />

favourable <strong>for</strong> primary production in valleys. This edaphic gradient also occurs at intermediate<br />

scale on the plateau landscapes where run-off from interfluves improves the soil moisture regime<br />

of run-on areas, such as dambos. At a small-scale, termite mounds also discharge run-off onto the<br />

surrounding area thereby creating mounds with deficient soil moisture, especially in drought<br />

years. Mound-building termites move the subsoil that has a higher clay content onto the land

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 16<br />

surface. Because of this engineering work, termite mounds have soils that are more clayey than<br />

those of the surrounding areas, although their nutrient status may not necessarily be higher. All<br />

these soil-water processes create heterogeneity at different landscape scales and produce a variety<br />

of habitats in the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> that support differing biological communities.<br />

2.5 Biophysical Processes<br />

Although the major tectonic processes on the Central <strong>Africa</strong>n plateau ended more than 2 million<br />

years ago, geomorphological processes are still active today in the ecoregion and are controlled<br />

primarily by rainfall (Cole 1963). Geomorphological processes are continuously modifying the<br />

relief and drainage, soils and micro-climate, thereby creating conditions more favourable <strong>for</strong><br />

some plants and less favourable <strong>for</strong> others. In turn, this brings about the extension of some<br />

vegetation communities and the recession of others of which only relicts may remain in the<br />

future. The Central <strong>Africa</strong>n plateau of the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> is being dissected in ongoing<br />

erosion cycles, especially at its edges, but also within itself. It is these processes that trigger the<br />

ever-changing composition of vegetation communities in the ecoregion and have implications <strong>for</strong><br />

the conservation of biodiversity, especially in the face of climate change.<br />

Early hominids in <strong>Africa</strong> used fire at least 1.5 million years ago (Goldammer 1991) and have<br />

ever since acted as a dominant ecological factor influencing vegetation. The earliest positive<br />

evidence of the use of fire by man in central <strong>Africa</strong> is dated more than 53,000 years ago (Clark<br />

1959). It is also argued that during the 1800 years since the Iron Age man occupied the <strong>Miombo</strong><br />

<strong>Ecoregion</strong>, vegetation changes have been brought about mainly through the burning and<br />

cultivating activities of man (West 1971).<br />

Fires in the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> occur regularly and frequently and originate from people<br />

preparing land <strong>for</strong> cultivation, collecting honey or making charcoal. Some fires are set by<br />

hunters, either to drive animals or to attract them later to the grass re-growth areas that were<br />

burnt, and by livestock herders to provide a green flush <strong>for</strong> their livestock and to control pests,<br />

such as ticks. Generally, people use fire to clear areas alongside paths connecting rural<br />

settlements. Such practices have probably been carried out <strong>for</strong> millennia. The fires occur<br />

throughout the dry season but most occur from July to October (Chidumayo 1997) and are<br />

fuelled largely by grass and woody plant leaf litter. Fire intensity is there<strong>for</strong>e linked to grass<br />

production in the previous rainy season, intensity of grazing and extent of woody plant cover.<br />

Fires tend to be more frequent and intense in areas of low woodland cover, medium to high<br />

annual rainfall, low grazing and low to medium human population density.<br />

Palaeo-fire regimes have varied with the influence of climate and man. It is difficult there<strong>for</strong>e to<br />

draw a general prehistoric fire regime in the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong>. Even the present-day fire<br />

regime is difficult to define from objective data because direct field observations are too scarce<br />

and scattered, while satellite determination of fire and burned areas is still not able to give a good<br />

regional view of the phenomenon throughout the year (Delmas et al. 1991). At local scale fire<br />

return periods range from 1 to 2 years, but at regional scale this is estimated at 3 years (Frost<br />

1996).<br />

The impact of fire on vegetation depends on the intensity and timing in relation to plant<br />

phenology. Intensity varies with time of burning and amount of fuel. Late dry-season (August–<br />

November) fires are more intense and destructive than fires in the early dry season (April–July)<br />

when much of the vegetation is green and moist. Usually fire intensities in the late dry season are

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 17<br />

5–18 times those observed <strong>for</strong> early dry season fires (Frost 1996). Late dry season fires are also<br />

more destructive because they occur when trees have flushed.<br />

Response to fire is variable among tree species. The extremes of the response continuum are<br />

defined by intolerant species that cannot survive fire, and are there<strong>for</strong>e are restricted to fire<br />

protected areas, and fire-tolerant species that survive regular intense fires. The trees of evergreen<br />

<strong>for</strong>ests (e.g. Cryptosepalum, swamp and riparian <strong>for</strong>ests), are nearly all highly intolerant of and<br />

easily damaged by fire, but trees in frequently burnt savanna vegetation in medium to high<br />

rainfall areas, including Brachystegia and Julbernardia species, are all fire tolerant. However, it<br />

is also true that all trees and shrubs will eventually be eliminated from savanna vegetation if the<br />

fires are sufficiently intense, and repeated during the late dry season over a sufficient number of<br />

years (West 1971). Under such conditions, the woody plants that persist are only those species<br />

which survive fire by underground tissues, from which they are able to re-sprout after fire during<br />

the next growing season. Grassland, in areas where edaphic conditions permit tree growth, is the<br />

ultimate product of fire because it is composed of plants most tolerant of fire. These plants are<br />

characterised by aerial parts that die off seasonally in the dry season and/or have dormant buds<br />

that are protected from fire damage by soil (geophytes and hemicryptophytes), or dead tissues<br />

just above the soil surface (chamaephytes) such as leaf bases or bulbs. Thus fire can cause<br />

changes in species composition and structure of vegetation. Frequent late dry-season fires<br />

eventually trans<strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong>est or woodland into open, tall grass savanna, with only isolated, firetolerant<br />

canopy trees and scattered smaller trees and shrubs (e.g. chipya vegetation). In contrast,<br />

woody plants are favoured by both early burning and complete fire protection. Fire there<strong>for</strong>e is<br />

one of the key ecological factors in <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> and its management has considerable<br />

implications <strong>for</strong> biodiversity conservation.

3.1 <strong>Ecoregion</strong> Boundary<br />

3. BIOLOGICAL FEATURES AND SPECIES<br />

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 18<br />

The revised <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong>, also termed the Southern Caesalpinoid woodlands, is an<br />

amalgamation of a number of the smaller ecoregions shown on the WWF-US Conservation<br />

Science Programme map "Terrestrial <strong>Ecoregion</strong>s of <strong>Africa</strong>" (WWF 1999). It is a broad,<br />

heterogeneous region that covers a large part of south-central <strong>Africa</strong>, but with many internal<br />

similarities and links. In many respects the revised <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> can be considered a<br />

"super ecoregion" or biome.<br />

This super-ecoregion is a broader unit than true miombo woodland (defined as woodland<br />

dominated by trees of the genera Brachystegia, Julbernardia and Isoberlinia with a welldeveloped<br />

grass layer), and is defined by the dominance (or high frequency) of trees belonging to<br />

the legume sub-family Caesalpinioideae, such as Brachystegia, Julbernardia, Isoberlinia,<br />

Baikiaea, Cryptosepalum, Colophospermum and Burkea. Its distribution and subdivisions are<br />

shown in Figure 4.<br />

White's original vegetation map (White 1983) was used as a basis <strong>for</strong> the revision, modified<br />

using a number of national and regional studies 1 . The final map closely follows the boundaries of<br />

the White's Zambezian Regional Centre of Endemism, except <strong>for</strong> the transition to the Guinea-<br />

Congolia and Zanzibar-Inhambane phytochoria. It also broadly corresponds to the broad-leaved<br />

dystrophic savanna woodlands of southern <strong>Africa</strong> (Huntley 1982).<br />

The revised <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> extends from the upper edge of the Angolan escarpment in the<br />

west to the beginnings of the coastal woodlands and <strong>for</strong>ests of Mozambique and Tanzania in the<br />

east (Southern Zanzibar–Inhambane coastal <strong>for</strong>est mosaic of Burgess et al. 2004), although it<br />

does not include those types. To the west and southwest it is bounded by Kalahari Acacia<br />

woodlands in Namibia and Botswana (Kalahari Acacia–Baikiaea Woodlands of WWF, in part),<br />

and to the south by Highveld grassland and mixed Acacia woodland in South <strong>Africa</strong> (Highveld<br />

Grasslands of WWF). To the north it grades into Guinea-Congolian moist evergreen <strong>for</strong>est of the<br />

Congo Basin (Southern Congolian Forest–Savanna Mosaic of WWF), while in the north-east it is<br />

bounded by dry Acacia-Commiphora bushland in Tanzania (Southern Acacia–Commiphora<br />

Bushlands and Thickets of WWF). Nomenclature of the revised units is quite different from that<br />

of the original WWF map, and in many cases the units are substantially different. A comparison<br />

with the WWF-US <strong>Ecoregion</strong> map is given in Table 1. The total area of the <strong>Miombo</strong> ecoregion<br />

(excluding water bodies and mountains) is 3,649,568 km 2 .<br />

3.1.1 Inclusions and Exclusions<br />

Although within the geographical extent of the southern Caesalpinoid woodlands, Afromontane<br />

<strong>for</strong>ests and grassland (units 76, 77, 78, 80 (part) of WWF) are excluded from the biological and<br />

other descriptions of the ecoregion. Their ecology and species composition are very different.<br />

Also excluded are large water bodies such as lakes Kariba, Malawi and Tanganyika have been<br />

excluded.<br />

1 National and regional studies used were: Acocks 1975, Barbosa 1970, Bekker & de Wit 1991, Giess 1971, C. Hines<br />

(pers. comm. 2002), Low & Rebelo 1998, Mendelsohn & Roberts 1997, Mendelsohn et al. 2000, Pedro & Barbosa<br />

1955, Timberlake et al. 1993, Timberlake et al. 1994, Wild & Barbosa 1967.

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 19<br />

Figure 4. <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> – vegetation types (from WWF SARPO 2003).

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 20<br />

Edaphic grasslands, floodplains, dambos and wetlands are, however, included within the revised<br />

ecoregion. They are considered to be an integral part of the woodland landscape and ecological<br />

processes, and functionally are not separable.<br />

Table 1. Revised <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> vegetation units. 2<br />

Vegetation unit WWF (1999) unit area (km 2 )<br />

Itigi thicket 48 15,405<br />

Cryptosepalum dry <strong>for</strong>est 32 37,908<br />

Wet miombo woodland 49 (most), 50 1,358,175<br />

Dry miombo woodland 52, 53 1,214,533<br />

Burkea–Terminalia woodland 57 (part) 96,162<br />

Mopane woodland 54 (part), 55 (part) 384,037<br />

Baikiaea woodland 51, 58 (part) 260,171<br />

Acacia–Combretum woodland 54 (part) 103,887<br />

Wetland grasslands 56 (part), 63 179,290<br />

Other areas (not part of ecoregion), e.g. water<br />

bodies, mountains<br />

167,636<br />

TOTAL 3,817,204<br />

3.2 Vegetation Types<br />

The two characteristic features of the Southern Caesalpinoid Woodland <strong>Ecoregion</strong> are the<br />

presence of woodland dominated by trees from the legume subfamily Caesalpinioideae, such as<br />

Brachystegia, Julbernardia, Isoberlinia, Baikiaea, Cryptosepalum, Colophospermum and<br />

Burkea, and the presence of a well-developed grass layer composed of C4 grasses. Caesalpinoid<br />

woodlands are composed of pinnate broad-leaved tree species, most being deciduous <strong>for</strong> at least<br />

a short period each year, the seasonality being related to a period of water stress and/or low<br />

temperatures. The woodland canopy is from 6 to 20 m in height, and ranges from 20% cover to<br />

almost closed-canopy <strong>for</strong>est.<br />

Caesalpinoid woodlands are mostly found on nutrient-poor soils (except Colophospermum and<br />

Acacia–Combretum woodland). Vegetation composition and structure are determined by climate<br />

(rainfall amount, length of dry season, mean temperature, frost), position in the landscape and<br />

soil type. Most changes in vegetation type within the ecoregion are gradual. Fire is an important<br />

feature.<br />

Another characteristic feature is the presence of large termite mounds, especially where sub-soil<br />

drainage is impeded. These are composed of cation-rich (particularly calcium) soils owing to<br />

their high clay contents, and generally have lower soil moisture levels. Termitaria support very<br />

different species from the surrounding woodlands. Their presence, as nutrient-enriched 'islands',<br />

is of major significance <strong>for</strong> both species diversity and woodland ecology.<br />

2 Areas taken from version of original hand-drawn map of Timberlake, digitized by WWF SARPO GIS Unit in 2001.

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 21<br />

The main genera of Caesalpinoid trees have explosively-dehiscent pods and seeds that are not<br />

distributed far. Genera dominant in wet and dry miombo vegetation are mostly ectomycorrhizal<br />

(they have symbiotic fungi associated with the root cortex), a feature often associated with<br />

impoverished phosphorous-deficient soils (Högberg 1986, Högberg & Piearce 1986) and <strong>for</strong>est<br />

trees, while the genera dominant in Baikiaea, Burkea–Terminalia, mopane and Acacia–<br />

Combretum woodlands are all endomycorrhizal (fungal hyphae penetrate the root cells), which is<br />

much more common in the tropics.<br />

Caesalpinoid woodlands are tolerant of significant damage from drought, fire, frost and<br />

megaherbivore browsing, as most of the major trees can readily coppice. This distinguishes them<br />

from moist <strong>for</strong>ests and from Acacia savannas which reproduce and recover more readily from<br />

seed.<br />

The ecoregion is divided into nine major vegetation or habitat types, each with a distinctive<br />

ecology and species composition.<br />

Itigi-like thicket: Dry deciduous <strong>for</strong>ests are found in the north east (the Itigi thickets of Tanzania<br />

and Zambia), dominated by Baphia and Combretum species and Bussea massaiensis. Further<br />

south, in the Zambezi and Shire valleys, there are similar thickets characterised by earlydeciduous<br />

Combretum shrubs and scattered emergent deciduous or evergreen trees. In places<br />

Xylia torreana <strong>for</strong>ms a canopy. Many of these thicket patches are too small to map at the present<br />

scale. They are of significant conservation interest owing to their limited extent.<br />

Cryptosepalum dry <strong>for</strong>est: Dry evergreen <strong>for</strong>est dominated by Cryptosepalum exfoliatum is<br />

found on Kalahari sands associated with the upper Zambezi in western Zambia. Other typical<br />

species include Parinari excelsa and Marquesia species, often with lianas. Although the <strong>for</strong>est is<br />

evergreen, the type is clearly distinct from the moist <strong>for</strong>ests of the Congo Basin. Annual rainfall<br />

is around 900 mm.<br />

Wet miombo woodland: A species-rich woodland with a canopy usually greater than 15 m high.<br />

Dominant species include Brachystegia floribunda, B. glaberrima, B. taxifolia, B. wangermeeana<br />

and Marquesia macroura. Annual rainfall is reliable and usually more than 1000 mm, but less in<br />

areas on Kalahari sands. The herbaceous layer comprises tall grasses such as Hyparrhenia. In the<br />

wettest areas the dominant trees are only briefly deciduous, the canopy is almost closed, and<br />

shade-tolerant species (e.g. from the family Rubiaceae) are found in the understorey. A number<br />

of floodplains and swamp grasslands are found along major rivers such as the Zambezi, Kafue,<br />

Chambeshi and Kilombero, as well as extensive dambos on the gently undulating plateau.<br />

Within wet miombo there are inclusions of "chipya", an open non-miombo <strong>for</strong>mation with very<br />

tall grass and a high complement of evergreen species. This is thought to have been derived from<br />

<strong>for</strong>est patches through fire, and is found on richer soils.<br />

Dry miombo woodland: This type is floristically poorer than wet miombo with Brachystegia<br />

spici<strong>for</strong>mis, B. boehmii and Julbernardia globiflora dominant; B. floribunda is generally absent.<br />

The canopy is generally less than 15 m in height and trees are deciduous <strong>for</strong> a month or more<br />

during the dry season. Species of Acacia are found on clay soils in drainage lines. Annual rainfall<br />

is less than 1000 mm and less reliable than further north. The herbaceous layer consists of<br />

medium to tall C4 grasses. In drier areas, Julbernardia and Combretum become dominant. There<br />

is an extensive area on Kalahari sands in central Angola dominated by thicket-<strong>for</strong>ming<br />

Brachystegia bakeriana, which appears transitional to Baikiaea woodland.

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 22<br />

As dry miombo woodland is found on escarpments as well as on the plateau and coastal plain, the<br />

geomorphology and soils are more varied than with wet miombo. There is also a significant<br />

inclusion of mopane, Acacia and Combretum woodlands in places. There are no significant areas<br />

of floodplain grassland or wetlands, but seasonally waterlogged drainage-line grasslands<br />

(dambos) are common on the central plateau.<br />

Burkea–Terminalia woodland: This rather impoverished woodland type is found at the southern<br />

margins of the ecoregion. Although similar in structure and broad ecology to dry miombo<br />

woodland, it does not contain any of its defining species. Instead there is a high frequency of<br />

Burkea africana, Terminalia sericea, Combretum, Pterocarpus, Pseudolachnostylis<br />

maprouneifolia and other broad-leaved trees typical of dystrophic woodland, along with species<br />

of Acacia, Albizia and Peltophorum africanum. There are many rocky outcrops which support<br />

mesic species.<br />

It is principally found on the southern part of the central plateau at over 1000 m altitude. Annual<br />

rainfall is around 600 mm, with high variability. The type has been much modified by human<br />

activity.<br />

Baikiaea woodland: Baikiaea woodland varies in structure from almost dry <strong>for</strong>est or thicket to a<br />

moderately-dense woodland. It is characterised by a dominance of the deep-rooted tree Baikiaea<br />

plurijuga, and is confined to deeper Kalahari sands. Canopy height varies from 8 to 20 m,<br />

depending on rainfall. Other typical species include Burkea africana, Combretum collinum and<br />

Guibourtia coleosperma. The type is deciduous, often <strong>for</strong> some months. Annual rainfall varies<br />

from 500 to 800 mm, but the deep sands absorb and retain moisture well so deep-rooted trees<br />

retain their leaves <strong>for</strong> an extended period.<br />

Mopane woodland: Mopane woodland is characterised by the dominance of Colophospermum<br />

mopane with a canopy from 6 to 18 m high, depending on rainfall and soil depth. Trees are<br />

deciduous <strong>for</strong> some months of the year. The grass layer is generally poorly developed. These<br />

woodlands are species-poor; associated species include Acacia and those from the Capparidaceae<br />

family.<br />

It is associated with nutrient-rich clay soils of the wide, flat valleys such as the Limpopo, Save,<br />

Zambezi, Luangwa and Cunene. Altitude ranges from 300 to 900 m. Mopane woodland is a<br />

eutrophic (nutrient-rich) type with a different ecology to true miombo. Annual rainfall is around<br />

400 to 700 mm with high variability, but soil infiltration rates are low.<br />

Acacia–Combretum woodland: This type comprises open woodland to wooded grassland<br />

dominated by species of Acacia and Combretum, often with trees from the legume subfamily<br />

Papilionoideae. There are two variants. One is found up on the central plateau of eastern Zambia<br />

in dry miombo on areas of nutrient-rich soil, sometimes locally called "munga". It consists of<br />

open woodland to wooded grassland with a well-developed grass layer, and is frequently burnt.<br />

Along with Combretum and Terminalia, a number of mesic Acacia and Albizia species, and<br />

species from the families Papilionoideae and Bignoniaceae occur. The other variant is found<br />

where the central plateau falls away to the Mozambique coastal plain and Zambezi valley. The<br />

climate is generally warmer, and fire is less frequent. Acacia nigrescens and Combretum species<br />

are very common, and are associated with Lonchocarpus capassa, Xeroderris stuhlmannii,<br />

Sterculia africana, Adansonia digitata and Cordyla africana. Mopane is often present, but is not<br />

dominant or abundant. The grass layer is variously well or poorly-developed, depending on soil<br />

depth and rainfall.

<strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong> <strong>Report</strong>, page 23<br />

Wetland grassland: Edaphic grasslands, floodplains, dambos (seasonally waterlogged drainage<br />

grasslands) and wetlands are of sizeable extent in Zambia (Barotse floodplains, Kafue Flats,<br />

Busanga and Lukango and Bangweulu swamps), Tanzania (Lake Rukwa, Mavowsi/Igombe,<br />

Kilombero valley) and Malawi (Lake Chilwa). Wetland vegetation is often dominated by stands<br />

of papyrus (Cyperus papyrus) or reed (Phragmites mauritianus/P. australis) with floating-leaved<br />

aquatics. Floodplains are extensive areas flanking rivers that are occasionally flooded. They are<br />

usually more species-rich than wetlands, but are dominated by grasses and sedges. In seasonallyinundated<br />

areas, similar edaphic grasslands can be found, with a rich geophyte flora. Dambo<br />

vegetation consists of open grasslands with scattered trees, often rich in <strong>for</strong>bs and suffrutex<br />

woody plants.<br />

3.3 Species<br />

3.3.1 Plants<br />

The ecoregion contains around 8,500 plant species, of which about 54% are endemic (White<br />

1983). There are no endemic families. The Zambezian Regional Centre of Endemism (equivalent<br />

to the <strong>Miombo</strong> <strong>Ecoregion</strong>) probably has the richest and most diversified flora and the widest<br />

range of vegetation types in <strong>Africa</strong> (White 1983). It is the centre of diversity of both<br />

Brachystegia and Monotes, and also <strong>for</strong> geoxylic suffrutex species ("underground trees"), an<br />

unusual life <strong>for</strong>m. Of 98 geoxylic suffrutex species listed <strong>for</strong> <strong>Africa</strong>, 86 are recorded only from<br />

this area (White 1976).<br />

The genera Bolusanthus, Cleistochlamys, Colophospermum, Diplorhynchus, Pseudolachnostylis<br />

and Viridivia are endemic, while Androstachys and Xanthocercis otherwise only occur in<br />

Madagascar. In addition to the characteristic Caesalpinoid trees, species of Acacia, Combretum,<br />

Erythrophleum, Monotes, Parinari and Terminalia are typical of these woodlands. The Great<br />

Dyke in Zimbabwe (20–30 species), Katanga (Haut-Shaba) in the DRC (56 species), the Itigi<br />

thickets in central Tanzania/NE Zambia (5–10 species?), and the high plateau around Huambo in<br />

central Angola (between 200–500 species) are particularly rich in endemic species.<br />

Around 100 threatened species are thought to occur in the ecoregion, of which nine are<br />

Endangered or Vulnerable. There are 39 threatened tree species, of which 19 are Endangered or<br />

Vulnerable (Walter & Gillett 1998, Oldfield et al. 1998). Plant Red Data lists <strong>for</strong> a number of<br />

countries in the region are under preparation through the SABONET project.<br />

Major timber species are Baikiaea plurijuga, Guibourtia coleosperma, Pterocarpus angolensis,<br />

Afzelia quanzensis, Millettia stuhlmannii and Dalbergia melanoxylon. A number of trees are<br />

widely used <strong>for</strong> construction timber or firewood, including Brachystegia, Terminalia and Acacia<br />

species, Pericopsis angolensis and Colophospermum mopane. The tree Warburgia salutaris is<br />

severely threatened from over-harvesting <strong>for</strong> medicinal use. Various wetland plants are of<br />

economic significance including Phragmites and Cyperus papyrus, while important water weeds<br />

are Azolla, Eichhornia, Pistia and Salvinia. Many grasses are of great importance <strong>for</strong> grazing to<br />

livestock and wildlife, including species of Brachiaria, Digitaria, Eragrostis, Heteropogon,<br />

Hyparrhenia and Panicum.<br />

3.3.2 Mammals<br />

Perhaps the most conspicuous and charismatic feature of the ecoregion is the wide variety and<br />